- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Literary Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

As a reader, teacher, and scholar of Australian literature, I applaud any initiative directed towards increasing readers’ understanding of, and engagement with, Australian writing. Geordie Williamson’s The Burning Library sets out to achieve that goal. Through a mix of biography and literary review, Williamson seeks to recuperate the work and reputation of fifteen Australian writers whom he judges to have been underappreciated or sidelined by academics, publishers, and, consequently, the reading public. His stable of writers includes Marjorie Barnard, Flora Eldershaw, Xavier Herbert, Christina Stead, Dal Stivens, Patrick White, Jessica Anderson, Sumner Locke Elliott, Amy Witting, Olga Masters, David Ireland, Elizabeth Harrower, Thomas Keneally, Randolph Stow, and Gerald Murnane.

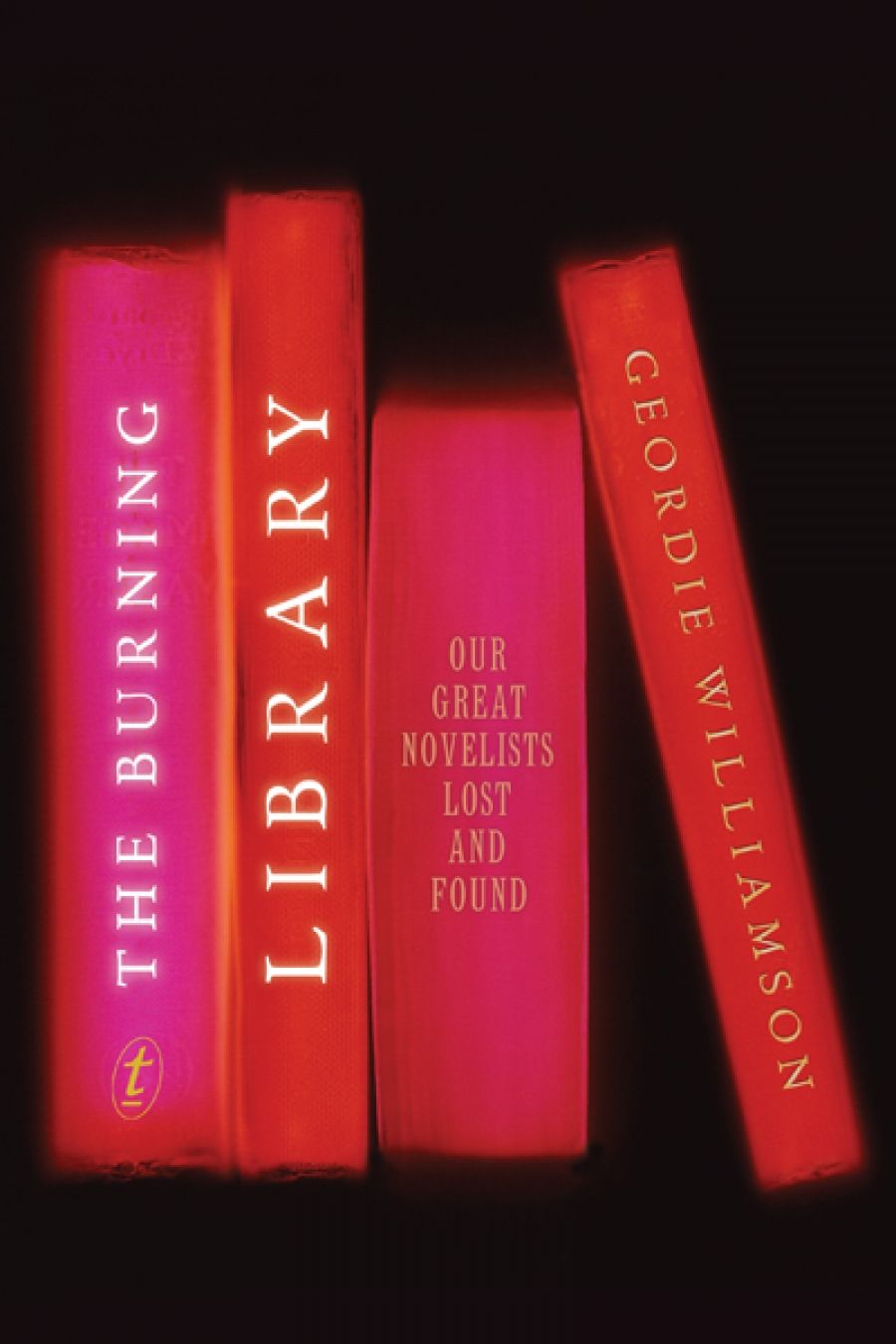

- Book 1 Title: The Burning Library

- Book 1 Subtitle: Great Novelists Lost and Found

- Book 1 Biblio: Text Publishing, $32.99 pb, 224 pp, 9781921922985

The Burning Library opens with the startling, and false, assertion that Australian literature began in 1938 with the publication of Xavier Herbert’s Capricornia, survived for approximately fifty years, then died. The ‘Ozlit’ to whichWilliamson is referring, and of which he is mourning the loss, is a mode of writing grouped loosely under the ‘umbrella of cultural nationalism’. It was ‘an idea, an aspiration, an infrastructure for literary endeavour, a collective investigation of our presence on this ancient continent’, and it was characterised by its persistent emphasis on the bush. This version of Australian literature is valorised as somehow more authentic and worthy of study than what is being published today, literature that is ‘severed from place and pitched at a fragmented and distracted audience’. In his quest to discover who or what (supposedly) killed Australian literature, Williamson sets his sights fairly and squarely on enemy number one: the academy. Apparently, we have reached a stage where ‘otherwise smart and thoughtful metropolitan critics evince a serial dislike of rural or non-urban narratives, in part because they recall a politically unpalatable past’.

For his first epigraph, Williamson cites Erich Heller on the idea that the most effective way to teach and inspire is through passion. There is no shortage of passion in these pages. Williamson cares deeply about his topic and aims to inspire his readers to return to, or discover, his chosen writers and their work. Williamson writes very well. His relaxed, easy style makes these engaged and engaging essays eminently readable. In his capable hands, the works of Christina Stead and Sumner Locke Elliott, in particular, come alive.

The volume opens with the statement: ‘This book is inspired by anger and hope.’ His hope to ‘rescue our collective literary achievement’ is what drives the narrative, but the anger – which is largely fuelled by a misunderstanding of the constraints and complexities of academic practices – paralyses much of his argument.

Williamson identifies correctly a number of contributing factors to the depletion of public awareness of our national literature: the increasing corporatisation of universities; financial pressures faced by publishers and literary journals; reduction of arts reviews in our major newspapers; shrinking budgets for research and libraries; and the recent move by ABC Radio to turn its signature show dedicated to literary discussion into more general arts coverage. It is, however, the academy that comes under sustained and ill-informed attack. I am left bewildered by many of the accusations. On what basis can Williamson assert that academics accept that Australian literature ‘is a temporary construction, well past its sell-by date’, or that academics are made uncomfortable by bush narratives? Williamson acknowledges the publication of ‘scholarly editions of older works, seminars and monographs devoted to significant literary figures, and a successful effort to create the first new permanent chair in Australian literature for half a century’, but goes on to argue that there is ‘an air of obligation surrounding these undertakings’ and that the ‘current approach to Australian literature admits that a once-vital relationship to its representative works has been cut’. What does he mean? These same academics, some of whose work he cites, run symposia, give public lectures and radio interviews, write book reviews, judge literary awards and write citations, edit literary journals, and publish critical work on the very same writers he says they ignore. In a book aimed at general readers, there is no need to overly engage with the wealth of critical material available, but to overlook it or suggest that it does not exist demonstrates a lack of intellectual rigour.

Williamson states that our ‘universities have almost ceased to preserve the best of our writing for future generations, despite employing scholars devoted to the work of past authors, because these writers no longer fit the parameters of a new pedagogy’. It is understandable how he might have come to this conclusion. Guided by the excellent AustLit database and using the Teaching Australian Literature Resource – established by concerned and dedicated academics – Williamson sought to ascertain which texts are being taught in Australian universities. A number of the claims he makes – about the absence of Stead, Murnane, Stow, Herbert – are incorrect. The database relies on overworked academics to update their teaching lists; it is not a perfect system. Also, to use the University of Sydney as an example, units of study are rotated on a biennial basis: thus, while Murnane might not appear to be taught in a particular year, The Plains will be taught the following year. There are also strict rules limiting the number of novels set on any unit of study. Academics are, therefore, prevented from teaching many of the texts they may desire to teach. These are just two small examples of the complexity of understanding university text lists. Perhaps Williamson would have been best advised to talk more with academics before penning the more misinformed, polemical aspects of this otherwise worthy book.

In The Burning Library, Williamson makes a case for his canon, and the case is well made. However, there appears to be an underlying anxiety about the need to define what might constitute a distinctly Australian fiction. Citing Nicolas Rothwell, Williamson wonders if Dal Stivens’ ‘dusty bush yarns mark a step in the direction of a distinctly Australian narrative form’. The bush narrative is set up as a counter to the ‘new pluralism’, with its focus on ‘feminism – a movement that expanded to encompass gay and lesbian rights – and an interest in minority writing more generally’, and as a way of turning critical attention away from ‘the transnational researches increasingly undertaken in the academy’ which downplay ‘notions of region or place’. Yet the national sits at the heart of the transnational. To read through a transnational lens is to appreciate how a text may celebrate the local – the historical, cultural, geographic, and political circumstances of its time and place – while also going beyond any boundaries of nation to explore what Philip Mead has called the ‘complex tangle of relations’ that connect texts to other cultures, languages, and issues. Indeed, Williamson’s reading of Stead’s fiction (perhaps unknowingly) praises its transnational nature: ‘Stead’s novels, still the most cosmopolitan in Australian literature, should be treated as the other half of our story; a reminder that we have never been apart from the world, that we remain implicated in events beyond our immediate horizons.’

A number of Williamson’s focal texts, like so many Australian texts, are no longer in print. As large multinational publishers go on merging, the prospect of small independent publishers continuing to produce quality Australian work or to keep Australian works in print looks increasingly dubious. Throughout The Burning Library, Williamson foregrounds Michael Heyward’s new series, Text Classics; a most worthy initiative deserving of praise. The contribution of publishers like Text and Giramondo to the maintenance of a healthy Australian literature cannot be understated.

It would be possible to read The Burning Library and despair about the current state of Australian literary studies. Like Williamson, I would be delighted if more Australians read more of our national literature. Perhaps we can take heart from David Malouf’s words, spoken at the recent Patrick White Award ceremony in Sydney. Marking the centenary of Patrick White’s birth, Malouf offered a somewhat personal reflection in which he noted: ‘we sometimes hear that [White] is no longer read – or not widely. The question really is what does widely mean? And what does it mean to be read? “Fit audience though few” is what Milton hoped for – a writer is kept alive, I would want to say, not by a wide readership, but by that small group of the best readers who are there in any generation to discover the books that are in some way extraordinary.’

There is no doubt that Williamson is one of the ‘fit audience’ of readers. In writing The Burning Library, he hopes to inspire ‘ordinary readers’ to ‘rescue our collective literary achievement’. It is an admirable intention, and I hope he succeeds. If only it were that simple.

Comments powered by CComment