- Free Article: Yes

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

When I heard that someone was writing Coetzee’s biography, I thought he must be either brave or foolish. After all, Coetzee’s own approach to autobiography is slippery, to say the least. J.C. Kannemeyer was (he died suddenly on Christmas Day 2011) a South African professor of Afrikaans and Dutch, a veteran biographer, and a literary historian. Coetzee co-operated fully, granting extensive interviews, making documents available, answering queries by email, and offering no interference. ‘He said he wanted the facts in the book to be correct. He did not wish to see the manuscript before publication.’ In other words, he behaved impeccably. Any suspicion that Coetzee’s Summertime (2009), in which a biographer researches the late J.M. Coetzee’s life, is based on his experience of being Kannemeyer’s subject is removed by the epilogue. Summertime was conceived and largely written before the biography was contemplated.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

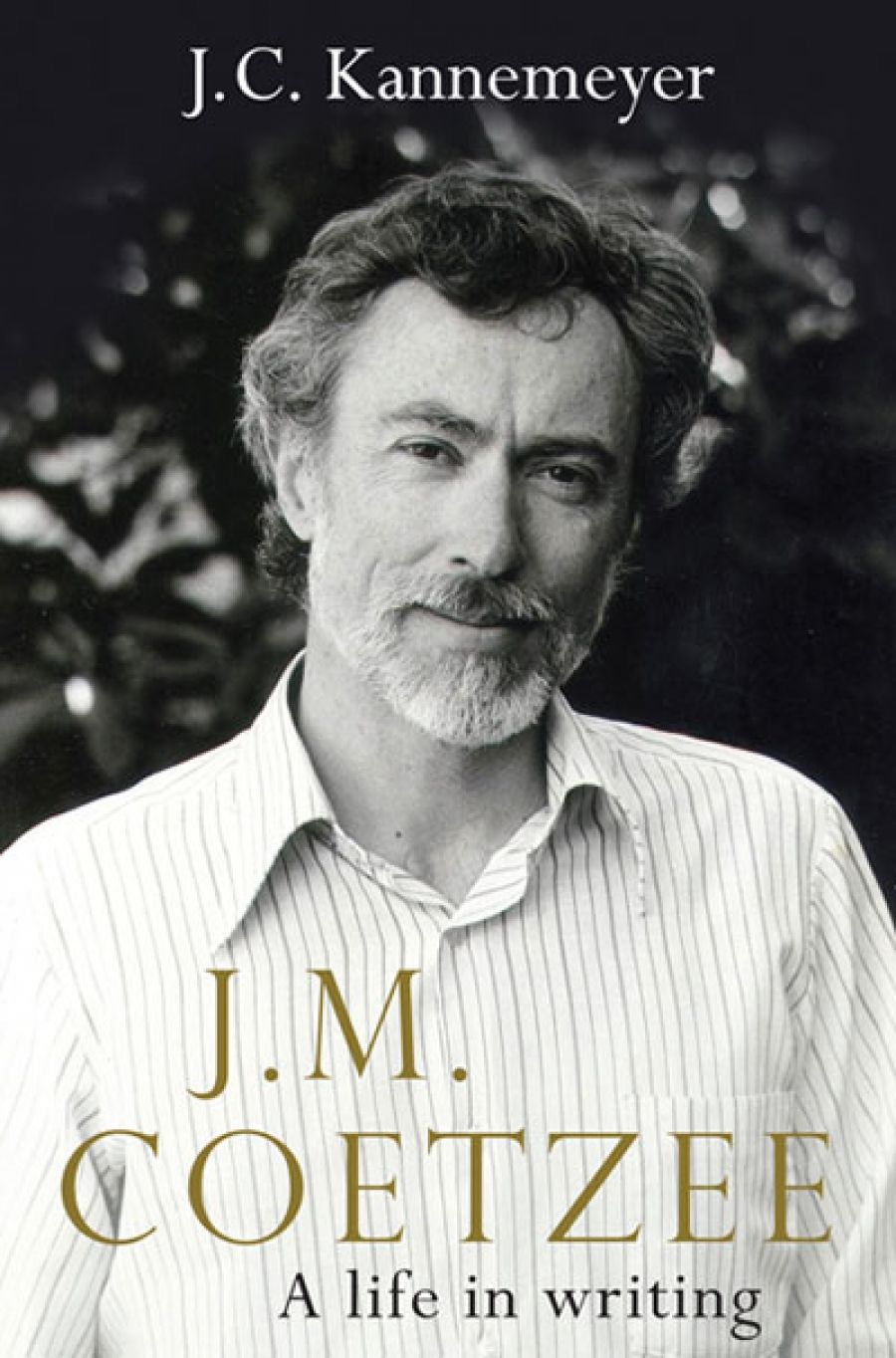

- Book 1 Title: J.M. Coetzee: A Life in Writing

- Book 1 Biblio: Scribe, $59.95 hb, 710 pp, 9781922070081

Part of the difficulty of reviewing this biography is understanding what one is reviewing. Firstly, it is a translation. Michiel Heyns includes a short note, explaining one or two difficulties, but, he says, ‘a work of non-fiction presents relatively few obstacles to the translator’. Questions still arise: for instance, a letter to Coetzee’s aunt on his uncle’s death is quoted, but the original language is not made clear. It was presumably written in Afrikaans and translated by Heyns, because the English has nothing of Coetzee’s usual elegance.

The second, and more puzzling, problem is what stage this biography had reached before Kannemeyer’s death. An unsigned editor’s note at the end explains that he had made some corrections and alterations based on readers’ reports. The editor, who, I deduce from the acknowledgements, is Hannes van Zyl, made further revisions based on recommendations from various colleagues. But in many ways this still feels like a draft. There are some continuity problems, as if chunks have been written independently and moved around. Thus early drafts of the first two paragraphs of Disgrace (1999) are compared with the final version in some detail and with some subtlety, but the following section provides a rather bald plot summary, repeating some of the information which has just been given. Some people are introduced twice within two pages, while others are mentioned without explanation, perhaps assuming knowledge of South African affairs. However, the achronological approach, whereby one aspect of a phase in Coetzee’s personal life or career is recounted, to be followed by another strand which overlaps in time, is presumably deliberate. I would sometimes have preferred a more consecutive narrative, but I can see that it would not have been easy to achieve.

Some decisions, too, were probably out of Kannemeyer’s hands. The almost outrageously copious endnotes are placed in an inconvenient fifty-page lump at the end of the book. There is much in these endnotes which is pure gold, but even if one realises it is there, to locate it one must memorise the note number, flip to the beginning of the chapter to establish the chapter number, find the corresponding chapter number in the endnotes, and flick through them to find the corresponding reference. Fair enough, perhaps, for scholars who are merely interested in following up the bibliographical details of a quotation, but the family history is apparently arbitrarily split between the main text and the endnotes, which also include a 147-line poem Coetzee wrote at school, followed by a long analysis spanning two closely printed pages, and the full text of a controversial speech he gave when Salman Rushdie’s visit to South Africa was cancelled in 1988. Some of this extremely interesting material should surely have been given prominence and readability in appendices, instead of relegated to the easily disregarded shunting yard that is the endnotes of a heavy 700-page volume.

The emphasis, as the subtitle indicates, is on Coetzee as a writer, while his personal life is adequately, if briefly, covered. Kannemeyer’s approach to literature is often disturbingly literal. In the early chapters he quotes chunks of Boyhood (1997) and Youth (2002), and even the novels, as if they are primary sources, though he does occasionally signal awareness of the dangers of this approach: ‘If Youth is a reliable guide, he seems to have experienced only the physical aspect of love,’ Kannemeyer writes. That’s a pretty big ‘if’. In any case, presumably any reader who is enticed to tackle this formidable volume would be familiar with Coetzee’s books, and these long quotes seem redundant.

Each novel is given a plot summary and a reception history. The former is unnecessary, but the latter is useful, especially for the early works, which were not widely reviewed internationally. Critical opinion is often quoted extensively and without comment, and some of Kannemeyer’s own interpretations lack nuance. Of the first part of Dusklands (1974), which deals with America’s involvement in the Vietnam War, he says, ‘Coetzee’s prose … derives some of its force from the reader’s realisation that the shocking reality can also stand as a metaphor for conditions in South Africa.’ In this case, ‘the reader’ in question is presumably Kannemeyer rather than readers in general, who would not necessarily react this way. In the Heart of the Country (1976) is subjected to a futile exercise in dating: ‘The period of the novel is clear from the absence of electricity and running water in the house …’ To say that anything is ‘clear’ in this novel is doubtful, and the temporal setting in particular is surrounded by uncertainty. Alongside this Kannemeyer includes quotations from his subject that emphasise his own much more uneasy relation to words and texts: ‘As far back as he can see he has been ill at ease with language that lays down the law, that is not provisional, that does not as one of its habitual motions glance back sceptically at its premises,’ Coetzee writes in Doubling the Point (1992).

On the positive side, however, along with early drafts, there are precious primary sources, including accounts from Coetzee’s teachers and classmates, course outlines and assignments from his early teaching career – fascinating – and some of his very early publications, including a chastely ravishing love poem from a university magazine:

If you will love me now

we shall not fear

leopards,

for over us will stand

one with an arched bow

which is a symbol of love …

The censorship situation in South Africa is dealt with in some detail. Coetzee’s novels were never banned in South Africa – he has said he regarded it as a ‘badge of honour’ that he had never merited – but during the apartheid era they were all submitted to the censor, and some of the unintentionally comic censors’ opinions are quoted.

There is little here that approaches scandal, and nothing to impugn Coetzee’s reputation as a man of artistic and personal integrity. The most shocking allegation in the book is that in the 1970s Philippa Jubber, then Coetzee’s wife, told some friends that she held him responsible for the death of a pet dog run over when he left a gate open, an accusation made, perhaps hastily, by a party in an unhappy marriage. There is, however, much evidence of Coetzee’s wit. His dealings with interviewers are famous. He told one, with surely conscious ambiguity, ‘that as much thought and effort should go into formulating the answer as went into formulating the question’. Another interviewer asked him to describe the room in which he writes. He obliged, ending with, ‘To my right is the desk I used when I was at school; in its drawers I keep stationery.’ The last detail strikes me as hilarious, but then I have always discerned in his work a deep vein of humour which escapes many other readers.

On the face of it, there is a mismatch between Kannemeyer, with his rather dogged approach to literature and his less than incandescent prose, and his subject. But despite the manifold irritations of the book, perhaps he was the right person for this job, which is a considerable labour, marshalling huge volumes of information to present as the first biography of someone who will doubtless be the subject of many more. Someone who could write with the beauty, acumen, and wit Coetzee displays in every sentence might have overreached. Kannemeyer’s biography, with all its faults, is solid, unpretentious, and thorough, and provides the groundwork for future generations of research.

Comments powered by CComment