- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

To go into any bookshop, if you can still find one, is to be amazed at the space devoted to militaria: endless shelves of books not just about the two world wars and Vietnam, but all wars in all times. This vicarious fascination with war echoes another phenomenon of our time: the rise of overt public respect for soldiers.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

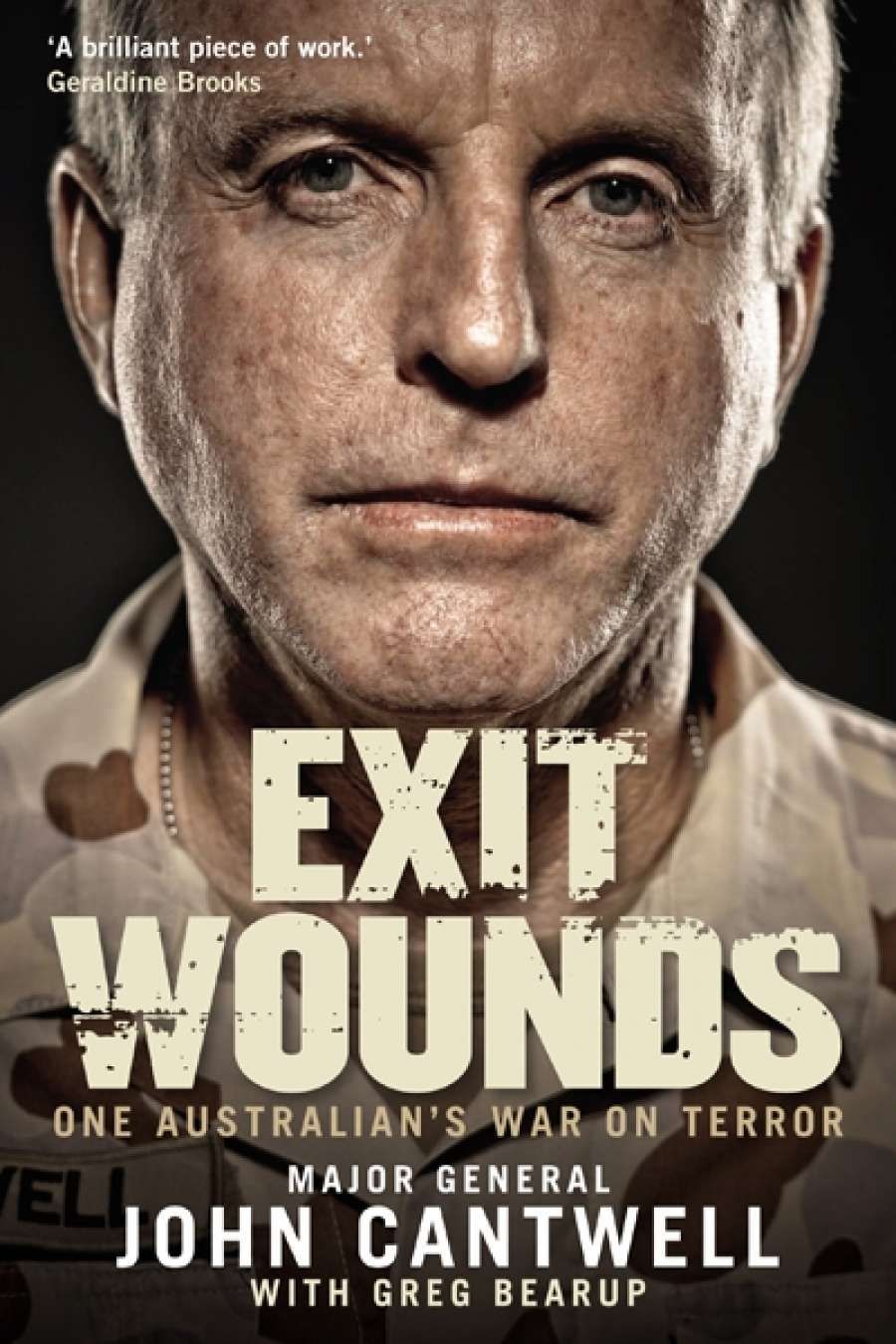

- Book 1 Title: Exit Wounds

- Book 1 Subtitle: One Australian’s War on Terror

- Book 1 Biblio: Melbourne University Press, $34.99 pb, 383 pp, 9780522861785

It was not always so. While the dead and the veterans of the world wars were generally honoured in Australia, those who served in Korea and Vietnam were often ignored and sometimes met with hostility. But the public mood has now largely changed to one of unquestioning support for the Australian Defence Force (ADF). Prominent displays of respect for the military have become a bipartisan political imperative, to the point of dictating policy.

For example, in August five Australian soldiers were killed in Afghanistan in one twenty-four-hour period, three in an insider attack by an Afghan soldier, and two in a helicopter crash. This prompted Prime Minister Julia Gillard to cut short her participation at a South Pacific Forum in the Cook Islands. Announcing that this was ‘the most losses in combat since the days of the Vietnam War and the battle of Long Tan’, Ms Gillard said she needed to return to Australia for briefings. Leaving aside the strange comparison (why are we so obsessed with such ‘records’?), the prime minister seemed to dismiss the role of preventative diplomacy. Are we not constantly told that the reason Australia participates in such forums is precisely in order to reduce the risk that ADF personnel will be involved in conflict?

In such a climate of public opinion, it may seem sacrilegious to wonder whether unquestioning support for the military is healthy, either for the body politic as a whole or even the defence force itself, but in effect Major General John Cantwell’s memoir, Exit Wounds, raises just that question. For if public respect for the military, fostered by governments, is so intense that it stifles debate over how the defence forces are deployed, this support is actually doing a disservice to personnel.

There are two aspects to Exit Wounds. One is General Cantwell’s story: joining the Army as a private in 1974, he served in the First Gulf War in 1991 and in the Occupation of Iraq in 2006, and then commanded the Australian contingent in Afghanistan in 2010. The other is the argument of the book, the distillation of the lessons that Cantwell drew from his harrowing experience. Among other things, he concludes that the Australian effort in Afghanistan, concentrated on the province of Uruzgan, has been futile.

And yet, when he commanded the Australian troops there, Cantwell considered expressions of doubt as to the worth of their presence as being ‘disrespectful, even treasonous’. The use of the words ‘disrespect’ and ‘treason’ is telling: meaning that to question the validity of their deployment in Afghanistan was a personal insult to individual ADF members, as well as a deliberate assault on the authority of the Australian state. Strong stuff, and coming from a senior uniformed figure like Cantwell quite enough to make a civilian commentator safe at home think twice before airing any doubts. For who would tell the family of someone who had died in Afghanistan that their sacrifice was pointless?

But what if it were true? In fact, fear of being seen to be ‘disrespectful’ is a key reason why there wasn’t more, and earlier, opposition in Australia and in other Coalition countries to the Afghan War. If there had been less self-censorship, fewer Australian and Coalition soldiers might have died. An d it is not at all clear that the long-suffering Afghans would have been worse off if the Coalition had withdrawn some years ago because, as Cantwell puts it, ‘Our laudable national aid efforts are a miniscule drop in the ocean of misery and disadvantage in Uruzgan.’

Australian Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Air Chief Marshal Angus Houston, and US Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Marine General Peter Pace, pass a portion of the Australian War Memorial dedicated to Australian soldiers who were killed in the Iraq War. (Photograph D. Myles Cullen)

Australian Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Air Chief Marshal Angus Houston, and US Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Marine General Peter Pace, pass a portion of the Australian War Memorial dedicated to Australian soldiers who were killed in the Iraq War. (Photograph D. Myles Cullen) For himself, Cantwell has now reached the point where he ‘cannot justify any one of the Australian lives lost in Afghanistan’. This quote comes from Exit Wounds, but he spelt out his views in the October 2012 edition of the Monthly in an article unambiguously entitled ‘They Died in Vain – There Can Be No Happy Ending in Afghanistan’.

As a result, the reader is inexorably drawn to the conclusion that the respect shown to ADF personnel (not that they don’t deserve it – but that is a different question) actually facilitates their use as pawns in what Cantwell describes as a ‘grand strategic view of international affairs’. In this view, Australia ‘has no choice but to maintain strong bonds with a large and powerful friend, the United States. That friendship sometimes demands reciprocal payments, in the form of going to war and spending some lives.’

This calculation has been the basis of Australian strategy for more than sixty years, and the core of Cantwell’s story is how he ultimately came to reject it. He may well be the most senior Australian military officer ever to do so publicly.

The personal narrative of Cantwell’s book is no less compelling than the argument. It shows that, quite apart from those killed and injured, many of the pawns in Canberra’s ‘grand strategic view’ pay a heavy price in other, less visible ways.

Exit Wounds is an unusual addition to the militaria shelves, not least because it opens with a lacerating self-description of a nervous wreck in a psychiatric ward. Cantwell writes: ‘I am a serving major general in the Australian Army … I shouldn’t be here.’ It is certainly not the way Australians have been taught to think of their generals.

The road to the psychiatric ward began in 1991, when Cantwell served in the First Gulf War on exchange with the British Army. Incidentally, his account of this campaign provides some of the best reading in the book, as he and his two British offsiders criss-cross a featureless, apocalyptic battleground, dodging minefields and ‘friendly’ artillery barrages, navigating by dead reckoning when their GPS fails.

Then we get to the hand. Cantwell is standing in front of a trench containing Iraqi soldiers buried alive when American assault bulldozers breached their front lines. As he stands there, a ‘human hand reaches up from the churned sand … Dread wells up inside me … the dead hand jerks into life, snatching my hand in a vice-like grip … ’ This is only the beginning of one of the nightmares that Cantwell began to suffer during the First Gulf War, and which have been with him on and off ever since.

The incidence of post-traumatic stress disorder among veterans is now more recognised than it was, but Cantwell’s candour in describing his own plight, coming from such a senior commander, may be the finest service he ever does his fellow soldiers. More than that, he has done all Australians a favour. What is remarkable is that with this fine book General Cantwell has emerged as one of the more credible and vocal representatives of a type which has almost disappeared from our public life: an opponent of unreflecting participation in war. It is no disrespect to Cantwell to say that this is a weighty indictment of Australian society.

Canberra’s ‘grand strategic view of international affairs’ has a habit of prevailing over muted objection, and you don’t have to oppose all war to see that this is dangerously undemocratic. We would do well to absorb Cantwell’s message before the next call goes up for Australia to join an international military coalition abroad.

Comments powered by CComment