- Free Article: Yes

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

‘There is another world, but it is in this one.’ That is Paul Éluard, channelled by Patrick White as one of four epigraphs to The Solid Mandala (1966), a ‘doubleman’ of a novel avant la lettre.Other quotations appended to this story of Waldo and Arthur Brown are taken from Meister Eckhart (‘It is not outside, it is inside: wholly within’) and Patrick Anderson (‘… yet still I long / for my twin in the sun …’).

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

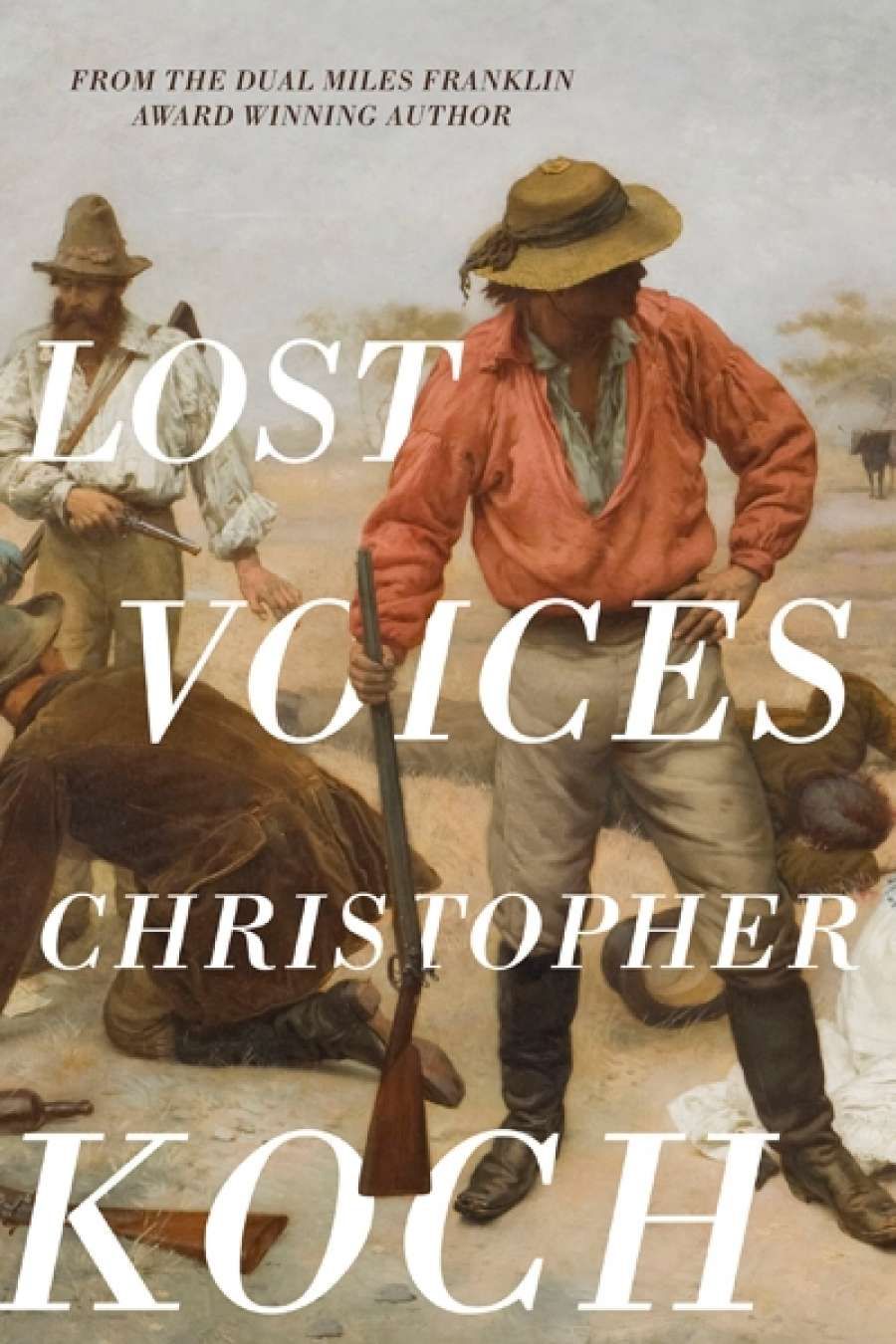

- Book 1 Title: Lost Voices

- Book 1 Biblio: Fourth Estate, $32.99 pb, 464 pp, 9780732294632

These quotations might, without fancy footwork, serve as epigraphs to Christopher Koch’s latest novel, Lost Voices, and not to it alone, being equally germane to his The Memory Room (2007) and The Doubleman (1985). In Lost Voices,as elsewhere, Koch tells two stories, here set in two distinct historical periods, which echo and mirror each other significantly. Indeed, this novel is in effect a triptych, and formally divided so. Books One and Three focus on painter Hugh Dixon, born in 1932 and reaching maturity in the 1950s. Book Two details the career and formative experiences of Martin Dixon, the father of Hugh’s great-uncle Walter, who spends a crucial period with utopian communitarian bushrangers in 1854. All three panels of the triptych are located in a lovingly and lyrically evoked Tasmania, Koch’s home ground. Both periods of the narrative feature a rape, murder, and the asserted presence of ‘evil’.

Despite its often dramatic content, Lost Voices is essentially low-key. This may be a function of Hugh Dixon’s first-person narration, which articulates the framing first and third sections, and thus of Hugh’s character. But does this not condemn Lost Voices to a certain dullness?

Consider the opening paragraph, always crucial in establishing a rapport with the reader (c.f. ‘Unemployed at last!’).

Late in life, I’ve come to the view that everything in our lives is part of a pre-ordained pattern. Unfortunately it’s a pattern to which we’re not given a key. It contains our joys and our miseries; our good actions and our crimes; our strivings and defeats. Certain links in this pattern connect the present to the past. These form the lattice of history, both personal and public; and this is why the past refuses to be dismissed. It waits to involve us in new variations; and its dead wait for their time to reappear.

Perhaps William Faulkner put it better in Requiem for a Nun (1951): ‘The past is never dead. It's not even past.’ Doubtless it is unfair to expect Hugh Dixon to wield Faulkner’s rhetorical skills, but who would care to be held in a Hobart saloon bar by the ‘glittering eye’ of this speaker? What about ‘Late in life’ being followed a dozen words later by ‘in our lives’? Where was Koch’s eagle-eyed editor when he was needed? Is ‘joys and miseries’ meant to summon up Balzac from the realistic deep? Is all this unfair, or would a reader be justified in not wishing to persevere?

If she did, the reader would spend the book’s first 100 pages in the company of the young and then-adolescent Hugh Dixon, his family, his friend Bob Wall, Hugh’s father and his crucial act of fiscal folly, which leads Hugh to seek aid from his great-uncle Walter, a barrister by profession and aesthete by inclination. His house and stories trigger young Hugh’s interest in his great-great-uncle Martin, whose bildung may be read as a mid-nineteenth-century avatar of Hugh’s mid-twentieth-century one, both parts of the ‘lattice of history’. The young Martin, in or about 1854, half-voluntarily joins the utopian commune of ‘bushranger’ Lucas Wilson, and is thus witness to murder and rape, which presages young Hugh Dixon’s experiences in mid-twentieth-century Hobart.

What links these two narratives separated by a century is the notion of evil, which was so important in The Doubleman. In that novel one character, an aged Estonian exile, voices concerns that are The Doubleman’s:

Without God we grow sick … This is a sentimentality of the present time: to explain all evil as insanity. Not to believe that monstrous things can be done by people who are sane. Hitler was never insane; he was far more serious than that. He had come to an agreement: he had embraced evil.

No one points out to him, or to anyone else in Koch’s novels, that to ‘explain’ acts by the notion of ‘evil’ is to empower them with a sort of metaphysical bathos, depriving them of the pressures of history, pressures which not only condition but create character.

From what Christopher Koch said in an interview around the time of the publication of The Doubleman, it appears that he would disagree vehemently with this:

I tend to recoil at the sound of the term ‘social realism’ because, when I was young [he was born in 1932] Australian literature was something of a slave to that genre. I may have a narrow view of it, it always seems to me to imply a limitation where fiction simply portrays people acting within a particular social context … I’m interested in things that motivate people beyond their social situations: their imaginative and spiritual preoccupations; their private obsessions. I’m interested in mysteries; and I suppose I’m interested in the irrational.

To which Patrick White would doubtless say ‘Amen’. Such interest in mysteries and the irrational pervades Koch’s The Memory Room, with its ‘doublemen’s business’ of espionage in the physical world and with geminology, mystic twins, reincarnation, the tarot, and faeries in the metaphysical world. Similarly, Lost Voices’ nineteenth-century villain believes that ‘There’s certainly a life outside this one. An invisible world lies all around us, and we’re watched by invisible beings.’ This may have some influence on Martin Dixon, who contemplates the possibility that by joining the outlaws, ‘by coming to this hidden valley, he’d entered a place like the faery hill of fable: a region that nobody down in the flatland could ever know’.

Yet the next sentence is no less significant: ‘What followed caused his romantic intoxication to fade.’ Indeed, in both historical dimensions of the novel, romance and realism vie for supremacy. Hugh Dixon sees Max Fell, pornographer, rapist, murderer, thus: ‘His was no ordinary wickedness. At times one encounters people who seem genuinely possessed by a demon.’ Walter says of Fell: ‘We may be in the presence of genuine evil here, he said. That’s a rather rare thing.’ Indeed, and one feels that in Lost Voices intimations of evil are merely asserted, gestured at, insufficiently dramatised, or substantiated. The novel is less convincing in this respect than is The Doubleman.

Lost Voices ends, despite Hugh’s commitment as a painter to realism, to Andrew Wyeth and Edward Hopper, with an assertion of a belief in ‘the dimension of the angelic, and the life beyond this’. Tonally, the novel ends as blandly as it began. Perhaps this suggests for the octogenarian Christopher Koch the Miltonic condition of ‘calm of mind, all passion spent’ rather than the refusal of the octogenarian Philip Roth to ‘go gentle into that good night’. The eighty-three-year-old John Barth has opted for the Prospero position: ‘And every third thought shall be my grave.’ No country for old men, indeed!

Comments powered by CComment