- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

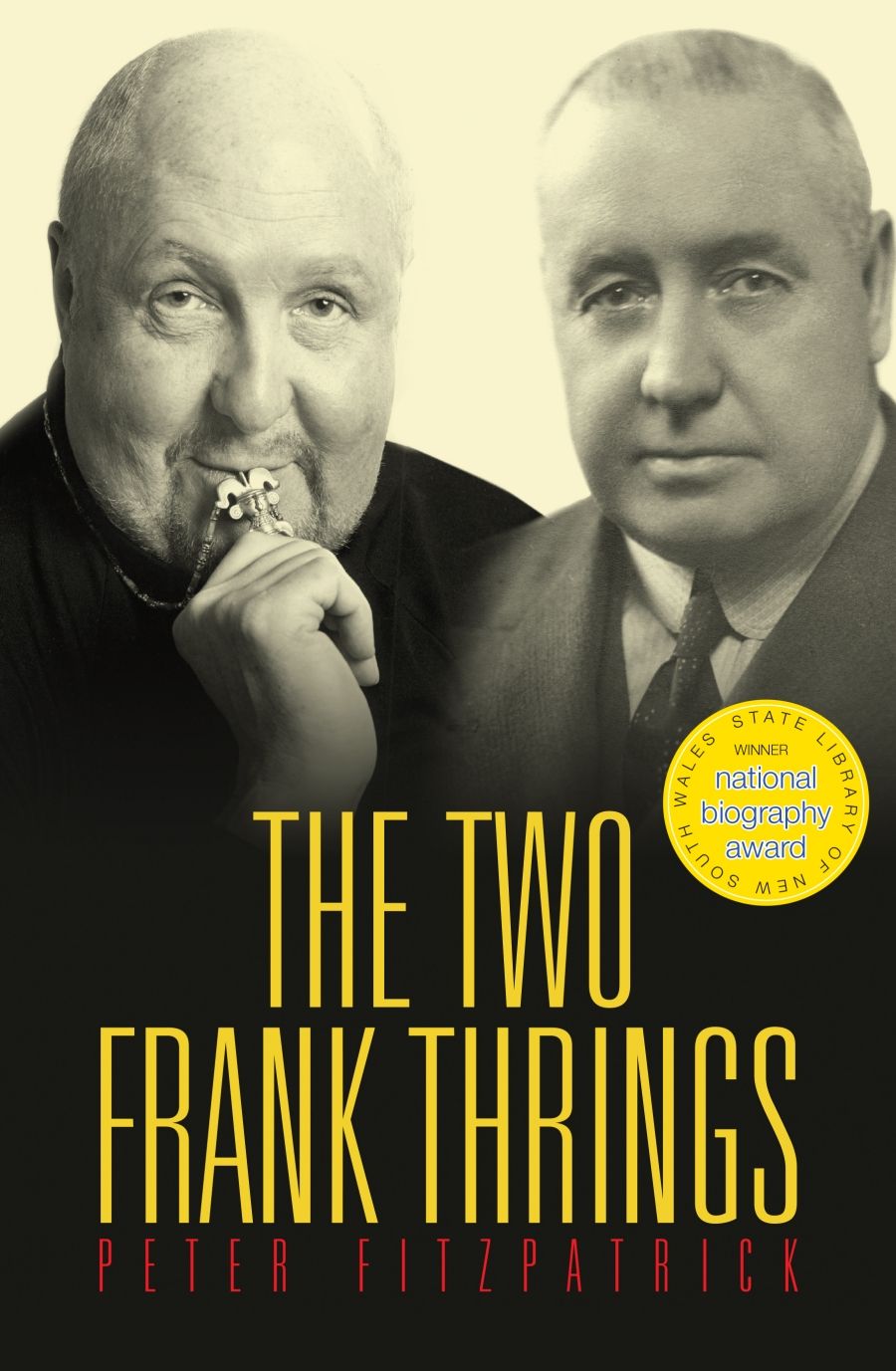

How lucky we were! My ‘baby boomer’ generation in Melbourne grew up on stories of the second Frank Thring (1926–94), which competed in outrageousness with the anecdotes we heard of Barry Humphries; and throughout the 1960s we had the opportunity – more so in the case of Thring, who had now settled back in Melbourne as a regular performer on stage and television, as Humphries began his lifelong commute to London – to catch both of these not-so-sacred monsters in the flesh and on their own home turf. (As I asked of the females of this species in a previous article in ABR – ‘Mordant Mots’, September 2007 – what is it about Melbourne that has produced such bizarre and brilliant creatures?)

- Book 1 Title: The Two Frank Thrings

- Book 1 Biblio: Monash University Publishing, $49.95 hb, 573 pp

There have already been a number of monographs devoted to Humphries’ career, and it is not even over yet, despite recent protestations. Thring has been dead nearly twenty years, Peter Fitzpatrick’s is the first major study of him to appear, and it occupies only half a book. But if it is quality we are comparing, half a loaf in this case is better than four. And the half-loaf turns out to be a mille-feuille. With more wit and style than in all those tomes on Humphries put together, Fitzpatrick, in a mere 250 pages, assembles an intricate confection of biography, gossip, performance analysis, and social history. There is also, for starters, the other half of the loaf, the account of the first Frank Thring’s life (1883–1936), which is – the account as well as the life – every bit as flavoursome, colourful, multilayered.

Frank I had aspirations – cut off by his death at the age of fifty-three when his son was only ten – to becoming the first Hollywood-style cinema mogul in Australia. Was he in part a model (without the campery) for all those historical potentates that Frank II went on to make his signature roles in his international stage and film career, before returning home? In their different (but not so different) ways, both father and son were larger-than-life characters, and in Fitzpatrick they have found a chronicler with the energy and brio to match their epochal and epical qualities. He also has, as they did not, the psychological acuity to puncture their pomposities and to plumb the failings in their emotional lives. This lends poignancy to all the razzle-dazzle, a haunting pungency to the sweeter smells of their professional successes.

It is all the more impressive that Fitzpatrick has achieved this in the absence of any substantial cues or clues from his subjects. They left few letters, no diaries, no memoirs. For much of his primary evidence, Fitzpatrick has had to fall back on the stories they put about to others (friends, colleagues, the media) and that others (including enemies and rivals) have told or retold about them. ‘People with large personas tend to inspire tall stories in others,’ he remarks at one point. It is the task of the responsible biographer to cut these down to size while also allowing that, for the film-maker father, as for the actor son, ‘fantasy was a critical ingredient’ in their sense of self, in their public as much as their private personas.

To weigh the value of these stories, and to cover the gaps in the evidence between them, Fitzpatrick has had to be more reliant than usual on ‘inference’ and ‘imagining’. Part of his strategy is to concoct a series of stream-of-consciousness monologues for his two subjects, in their assumed voices but also in the third person, italicised, separated from the main narrative, and scrupulously labelled ‘fictional’. For all its risks, or because of them, I rather prefer this strategy to his all-too-frequent recourse in the main narrative to those standard biographer’s fallbacks when faced with a lack of evidence: ‘would have’ and ‘must have’.

Perhaps those weasel-sounding constructions are not altogether avoidable, but, while I am in this (enviously) carping mood, let me also register my shock, given the superlative literacy of the rest of the text, at Fitzpatrick’s reference to the ‘precipitous’ marriage of Frank I to Frank II’s mother. With her ‘big-boned’ frame, Olive Thring may well have loomed as large as her groom, but surely neither was so mountainous. A gremlin, maybe with the same steep gradient in mind, gives us ‘Monte’ for Monty Woolley on several occasions when invoking the giant (in both senses) of the Broadway stage. The legendary headmaster of Melbourne Grammar in Barry Humphries’ time was never ‘The Reverend Hone’, as he is styled here, for all his other distinctions. And The Tiger, in the English title of the Jean Giraudoux play that Frank II saw in London in the 1950s was at the Gates, not the Gate. Probably, too, the penultimate monologue in the book is misdated: it assigns Frank II’s momentous move to Fitzroy from the family home in Toorak to 1987, when all the other evidence provided in the text fixes it at 1985. Despite this sprinkling of incidental errors and solecisms, I take my cap off to the editors and designers, as well as the author of this handsome volume. (Genuine footnotes, at the bottom of each page, rather than in an inconvenient clump at the back of the book, are a particularly welcome, and rare, feature these days.) Altogether, it is an auspicious hardback début for that relatively new kid on the scholarly publishing block, Monash University Publishing.

Let me end with a Thring story of my own – not a tall one, because I was there at the time. ‘There’ was the imposing Toorak house, ‘Rylands’, that Frank I had bought for his bride back in the 1920s and where Frank II was to continue to stay all the time that he lived in Melbourne until a dip in his fortunes prompted that decampment (shall we say?) to a less salubrious inner suburb. Rylands has now long been demolished, so I can’t check my story, but I vividly recall rushing over there with another Thring fan when it was first put on the market so that we could take a peek at all those accoutrements with which Frank II had reportedly filled it following his mother’s death: the chandelier in the bathroom, the upholstery decorated with disporting nude athletes in the manner of classical Greek vases, the black-painted walls, the little cinema for special screenings of who-knows-precisely-what kind of movies – but certainly not ones for general exhibition. Most of these things were there, true to the stories we had heard. But there was something else of which we had not heard, and that the estate agents on the day seemed intent on keeping under wraps, literally under wraps. There was a swimming pool in the back garden.

Normally, you would think, a pool was something any agent would flaunt – would have filled to the gleaming brim. But from what we could make out it was quite empty. It was difficult to be sure because it was shrouded all over with green baize, as if the Salome who had played opposite Frank II’s Herod in King of Kings (1961) had carelessly or contemptuously dropped her last veil there. (In the film, as Fitzpatrick reminds us, the actress concerned had controversially dispensed with the legendary veils altogether.) It was only when we went upstairs to the second-storey balcony, overlooking the back garden, that we twigged to a much more pragmatic explanation for the shrouding. The pool, as you could discern its lineaments from up there, was also quite unsuitable for general exhibition, not least on auction day. It described the shape of a very long penis, complete with balls that accommodated the two sets of steps leading into the water – when it was full, that is.

When would it have been filled last? Fitzpatrick does not mention it at all, but in its desolate state, this priapic pond seems touchingly emblematic of one of the pervasive themes of his book, relevant to both Frank Thrings: the disproportion of their sense of yearning to their sense of fulfilment in matters of the heart (and other parts of the body), the braggadocio of their public performance that covered the hurt, the loneliness, the sense of deprivation. In Fitzpatrick’s expert hands, their stories count among the saddest as well as the most scintillating in our annals.

Comments powered by CComment