- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

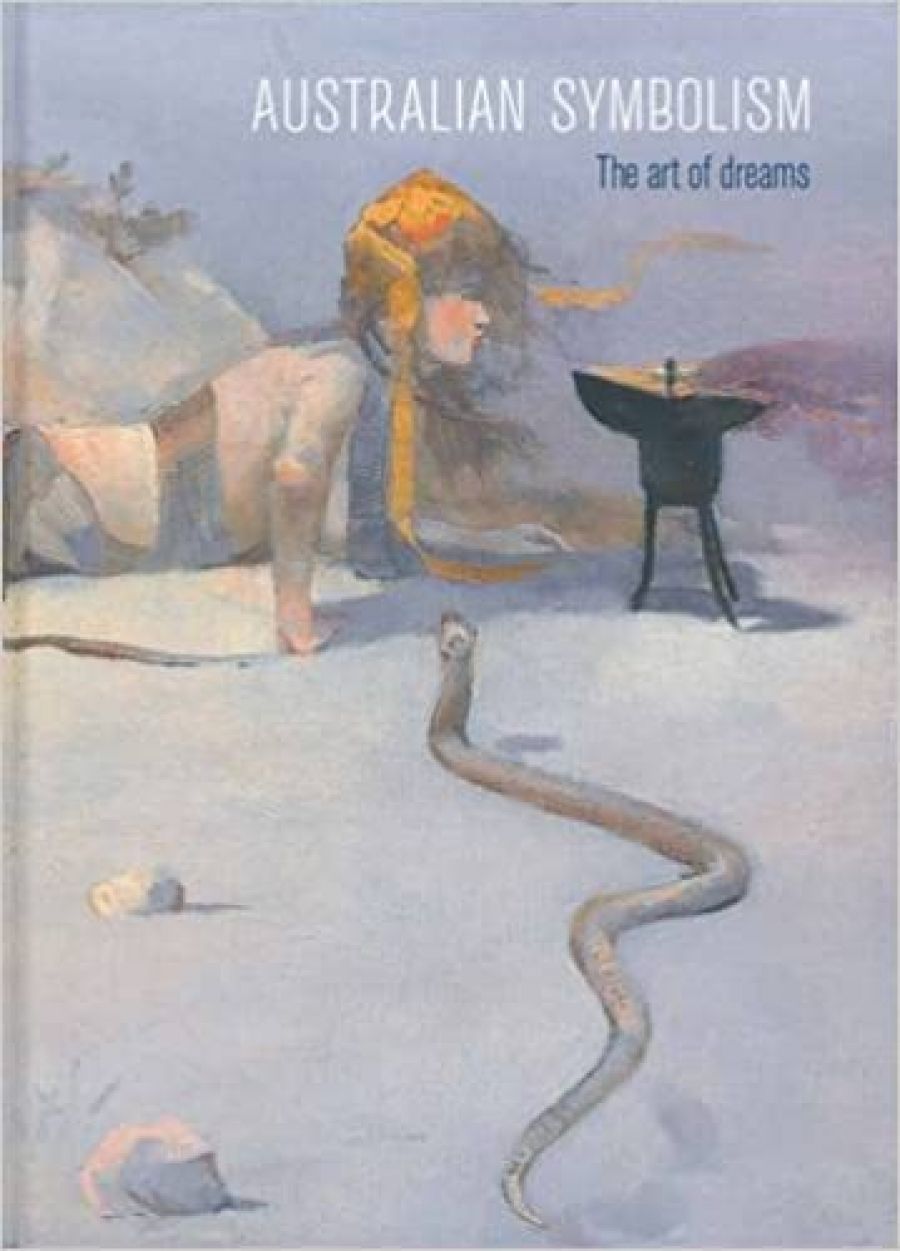

This year is proving a good one for Symbolism. An international conference entitled ‘Redefining European Symbolism’ was held at the Musée d’Orsay in April, followed shortly afterwards by four days on ‘The Symbolist Movement: Its Origins and Consequences’ at the University of Illinois, in Springfield. A third conference is planned for October at the Scottish National Gallery in Edinburgh to coincide with the exhibition Van Gogh to Kandinsky: Symbolist Landscape in Europe 1880–1910 (14 July–14 October); shown first at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam as Dreams of Nature: Symbolism from Van Gogh to Kandinsky and concluding at the Ateneum Museum, Helsinki. Meanwhile, Australian Symbolism: The Art of Dreams has recently finished at the Art Gallery of New South Wales.

- Book 1 Title: Australian Symbolism

- Book 1 Subtitle: The Art of Dreams

- Book 1 Biblio: Art Gallery of New South Wales, $35 hb, 159 pp

- Book 2 Title: Van Gogh to Kandinsky

- Book 2 Subtitle: Symbolist Landscape in Europe 1880–1910

- Book 2 Biblio: Mercatorfonds, £19.95 pb, 208 pp, 9781906270544

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Cover Path (no longer required): images/1_SocialMedia/2021/Nov_2021/META/download copy.jpg

Fine catalogues were published for both exhibitions, fruits of a resurgence in scholarly interest presented for a wide readership. The work of well-known artists is reassessed in fascinating new ways, and less familiar names prove worth remembering. Both books make important contributions to the scholarship of late nineteenth-century culture and should have useful lives long after the exhibitions have closed.

Symbolism was not an artistic style. It was not even exclusive to the visual arts, but was, rather, a heterogeneous, interdisciplinary, cross-media phenomenon entailing an attitude – a way of looking at the world. Its roots lie in philosophy, poetry, and music, and it was a poet, the Greek-French Jean Moréas, whose manifesto in Le Figaro of 18 September 1886 claimed Symbolism as the only term ‘capable of adequately describing the current tendency of the creative spirit in art’. For Moréas, the essential principle of art was ‘to clothe the idea in sensuous form’ – ‘idea’ being his key word. Just as Symbolist writers regarded poetic language primarily as an expression of inner life (Moréas retrospectively recruited Baudelaire, Mallarmé, and Verlaine as the three leading poets of the movement), so certain painters and sculptors in the late nineteenth century turned their gaze inward to convey allusive meaning, emotion, and sensory experience that was more than visual. In part, this was a reaction against Realism and Impressionism, which had then become, and are still considered, such supposedly objective avenues of artistic expression: against Gustave Courbet’s claim that ‘painting is an essentially concrete art and can consist only of the representation of things both real and existing’; or Tom Roberts et al. promising ‘to paint only as much as we feel sure of seeing’.

Charles Conder, Hot Wind, 1889, oil on board, 29.4 × 75 cm, National Gallery of Australia

Charles Conder, Hot Wind, 1889, oil on board, 29.4 × 75 cm, National Gallery of Australia

Both books cover the years from about 1880 until World War I, a period popularly identified here in Australia with the open-air nationalist and naturalist ‘Heidelberg School’. The first critic to note the possible application of Symbolism to pictorial art seems to have been Albert Aurier in his 1891 article ‘Symbolism in Painting’, published in the Mercure de France, proclaiming Paul Gauguin leader of the movement. Locally, when Artur Loureiro and Charles Conder exhibited what were probably the first examples of Australian Symbolist art in the late 1880s, reviewers called them ‘poetic’, ‘ideal’, ‘allegorical’, or ‘decorative’ and recognised their consciously cosmopolitan and contemporary intent. Alice Muskett’s work was described as Symbolist after her return from Paris in the 1890s; and by 1895 a Melbourne art critic could declare: ‘If Charles Douglas Richardson was a Frenchman, he would be described as a Symbolist.’ Of course ‘isms’ are useful, but they can also be limiting and misleading, and both books reveal that there are many ‘symbolisms’ and many ‘naturalisms’. Decisions by the authors of both books as to when to use ‘Symbolism’ and when to use ‘symbolism’ cannothave been made without debate.

Van Gogh to Kandinsky: Symbolist Landscape in Europe 1880–1910 clearly demonstrates that images of the landscape, in particular, can be suggestive as well as naturalistic. Its five authors have, between them, decades of expertise in later nineteenth-century art history and behind them the fabulous resource of the Leverhulme Trust-funded European Symbolist Research Network, directed by the author of three chapters, Professor Richard Thomson of Edinburgh University. While they explore the complexity of Symbolism as a movement (or, perhaps more loosely, a current), tracing its origins back at least as far as Romanticism and its repercussions forward to abstraction, theirs is not an exhaustive account of all its manifestations, but the first comprehensive study of Symbolist landscape painting across Europe. They look closely at two important forerunners, the Swiss-German Arnold Böcklin and French Pierre Puvis de Chavannes; then focus on artists of the avant-garde, including Gauguin, Vincent van Gogh, Odilon Redon, Edvard Munch, James Ensor, Wassily Kandinsky, and early Piet Mondrian, compared and contrasted with less widely known Scandinavian and Eastern European landscape painters; and with British figures, such as James McNeill Whistler, George Frederic Watts, and Frederic Leighton. In Australian Symbolism, Denise Mimmocchi, Curator of Australian Art at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, tackles many of the same complexities single-handedly and shows that information about European Symbolism arrived here as part of a package of modern trends, including British Aestheticism and the tail end of international Impressionism, which were adopted and adapted concurrently, sometimes even in the same work of art. Bertram Mackennal’s over-life-size Circe (1892–93) greeted visitors at the exhibition entrance, and Mimmocchi represents sculpture generously, noting the impact of Rodin’s ‘great dreams in marble’; as well as photography, ceramics, and jewellery. (Mackennal had met Rodin through the expatriate Australian Impressionist John Peter Russell, who himself produced a number of paintings that would have fitted comfortably in either Van Gogh to Kandinsky or Australian Symbolism.)

Both books are arranged thematically, with long chapters further divided into readable sections. Both are superbly illustrated. Van Gogh to Kandinsky, with its narrower focus on landscape, leaves artist biographies until the end and, in seven essays by four authors, drills deeply into various histories that interlock with art in the period: of music, literature, mysticism, science, medicine, and the burgeoning of psychology as a discipline; as well as nationalist expression and the massive population shifts from country to city that brought irreversible change and, for some, a deep sense of cultural loss. Mimmocchi brings together an enormous amount of information in Australian Symbolism, in a smallish format that is comfortable to handle and, happily, has an index. Her two long chapters, ‘Australian Artists and Cosmopolitan Currents’ and ‘Dreams of an Antipodean Arcady’, are made up of several short essays on individual artists and themes. While Symbolist-inspired works by a number of the artists she treats have been included in important exhibitions and publications before, this is the first time so many have been brought together and set so well in their local and international contexts.

Sydney Long, Pan, 1898, oil on canvas, 107.5 x 178.8 cm, Art Gallery of New South Wales

Sydney Long, Pan, 1898, oil on canvas, 107.5 x 178.8 cm, Art Gallery of New South Wales

Australian Symbolism tends to look backward and forward at the same time. Backward, a ‘native’ Arcadian mythology was envisioned – first as an antidote to the materialism, urbanisation, and industry of the booming 1880s, and then to the shock of economic depression of the 1890s – which involved sinuous eucalypts, dancing magpies or brolgas, and various ‘spirits’ of the environment personified in female form. Forward was the prospect of the new young federated Australia as a contemporary Utopia (the concept of art nouveau – new art – sat well with turn-of the-century Australian ideals). The seriously threatening kind of femme fatale found regularly in European Symbolist paintings did not materialise in Australia. Indeed, there is a niceness to Australian Symbolist women that allies them less to the Belgian and Germanic creatures of, say, Ensor, Félicien Rops, Gustav Klimt, or Franz von Stuck than to the wholesome, strapping ‘colonial girls’ described and depicted in popular illustrated papers at the time. They are usually more ‘symbolist’ than ‘Symbolist’. Although the Portuguese-born Loureiro had worked in France before he arrived here in 1884 and his Australian-Belgian sister-in-law knew Redon and the novelist Joris-Karl Huysmans, his girls in the moon and stars are delightfully decorative rather than decadent. Although oil and watercolour versions of Arthur Streeton’s Spirit of the Drought (c.1896) include human skulls among the desiccated bones at her feet, the spirit herself is a distinctly unmenacing pale pink girl waving a see-through shawl. Hot Wind of 1889, described by Conder as ‘the best work I have done’, symbolises a scorching Australian summer westerly in the person of a young, exotically draped woman, lying with a large snake in a parched (plein-air impressionist) riverbed, and blowing heat from a flaming brazier across the plains towards a distant town. Even though she is to be understood as both beautiful and dangerous, Conder’s ‘idea’ is, ultimately, drought: the climate with which Australians have learned to live.

While Conder reportedly became interested in séances and Richardson was well known for his affiliation with esoteric Spiritualism, there was no Australian artist who even approached the synthesis of subject, form, and meaning that remains so potent in the greatest works of Gauguin or Munch. Basically, much Australian Symbolism did not last. By the 1930s, when J.S. MacDonald championed Streeton for painting ‘the way in which life should be lived in Australia, with the maximum of flocks and the minimum of factories’, many of the Australian works included in Mimmocchi’s book had been forgotten (Hot Wind was ‘lost’ until six years ago; others were de-accessioned by museums). Presumably they seemed ‘just so last century’: too literary, too imaginative, ‘escapist’, Victorian – probably too close, while the popular and institutional love affair with ‘reality’ held sway, to Oscar Wilde’s fin-de-siècle assertion that ‘Lying, the telling of beautiful untrue things, is the proper aim of Art.’

Comments powered by CComment