- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Why, Alice Kessler-Harris’s friends kept asking her, are you writing a biography of Lillian Hellman – a good question of one of the world’s leading historians of women and work, who has just stepped down as president of the American Historical Association. If Hellman is remembered at all today, it is as a mediocre playwright, an ugly, foul-mouthed harridan whose luxurious comforts were provided by ill-treated employees, a blind supporter of an evil political system – and, above all, as a liar and thief who appropriated someone else’s life to make her own seem more heroic.

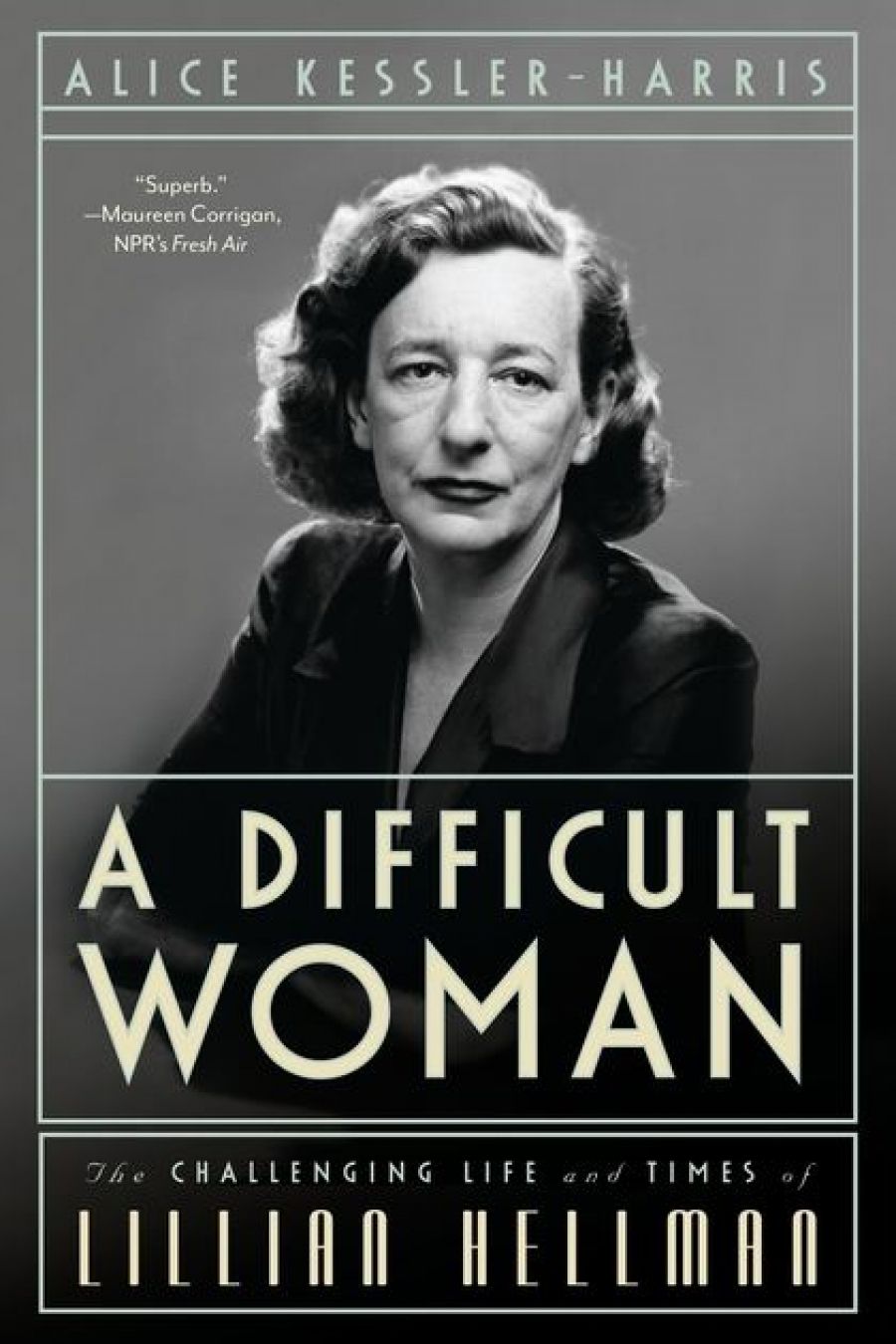

- Book 1 Title: A Difficult Woman

- Book 1 Subtitle: The Challenging Life and Times of Lillian Hellman

- Book 1 Biblio: Bloomsbury, $39.99 hb, 439 pp, 9781596913639

But Kessler-Harris, who began her career rescuing forgotten working women, remembered another Lillian Hellman – the one who provided a role model for the emerging women’s movement in 1969 with the publication of the first volume of her memoirs, An Unfinished Woman. Kessler-Harris was twenty-eight, recently divorced, the mother of a five-year-old daughter, the first woman to be appointed to the History Department at Hofstra University, New York. Attending consciousness-raising groups, reading Marx’s Das Kapital, finding common cause with other young women historians, she saw Hellman as someone to be emulated. Here was a woman who had forged her own literary and financial success, who went her own way sexually (her long relationship with Dashiell Hammett, like that of Simone de Beauvoir’s with Sartre, seemed heroic at that time), and who was politically courageous and outspoken. Forty years later, Kessler-Harris pays tribute to that woman in her new biography, A Difficult Woman: The Life and Times of Lillian Hellman, and asks why her reputation has sunk so low since those heady days of 1969.

Lillian Hellman was born in New Orleans in 1905 and brought up from the age of six in New York, a poor relation among prosperous relatives, and a Southern Jew among the newer arrivals from Eastern Europe. A touchy outsider, she found a place in the 1920s among the semi-bohemians of the publishing world, where she met and married the young writer Arthur Kober. The marriage lasted on and off, in New York and in Hollywood, until she met Dashiell Hammett, the famous writer of detective novels, in 1931, when she was twenty-six years old. During a rocky relationship (never a marriage) that lasted, with many reverses, until his death thirty years later, Hellman matured as a writer while Dash’s health and reputation went downhill. She made a fortune during the 1930s, first of all with The Children’s Hour (1934), a play about the devastation caused by accusations of lesbianism in a girls’ school, then with The Little Foxes (1939), Watch on the Rhine (1941), and, much later, Toys in the Attic (1960). ‘Well-made’ melodramas, they were critical failures but commercial successes. Children’s Hour, The Little Foxes, and Watch on the Rhine were made into movies and enabled her to sign lucrative contracts as a writer for Hollywood. From that time she lived extravagantly, enjoying the New York Plaza (‘where everything comes up in a silver service elaborate enough for royalty’), the farm she purchased outside New York City, and the Georgian townhouse on East 82nd Street, supported by a secretary, a housekeeper, and other household staff.

Like many others in the entertainment industries, Hellman became involved in left-wing politics during the 1930s, travelling to war-torn Spain in 1937, joining the Communist Party the following year, and spending four months in Moscow in 1944–45. These activities, neither illegal nor subversive at the time, caused her to be called before the Committee on Un-American Activities in 1952, where she achieved notoriety by managing to avoid both naming names and going to jail. After being blacklisted during the 1950s, she enjoyed a renaissance in the 1960s, when her plays were revived, and she held a number of teaching jobs at prestigious universities (where she was accompanied by her African-American cook and housekeeper). Sought after as a celebrity commentator and speaker, she was persuaded by publishers Little, Brown to write her memoirs, which came out as An Unfinished Woman in 1969, Pentimento in 1973, and Scoundrel Time in 1976.

The height of her new fame – and her downfall – came in 1977 when her story ‘Julia’, part of Pentimento, was made into a movie, with Jane Fonda as Hellman and Vanessa Redgrave as her friend Julia. When it emerged that Hellman had taken as her own the story of another woman’s life, a gathering storm of accusations that encompassed her whole life history left her reputation in tatters. She died in 1984, a broken woman.

The task that Kessler-Harris has set herself is to understand why this transformation in reputation took place. She makes it clear that the book is not really a biography, though her publisher insisted that it be listed as one. She prefers to call it a history; and that is what it is. As she points out, there are already several biographies, as well as Diane Johnson’s authoritative Dashiell Hammett: A Life (1983), that provide the details and the chronology of Hellman’s life. Kessler-Harris wanted to investigate how large historical changes shaped Hellman’s life and reputation. She therefore organises the book thematically, starting with an overview of Hellman’s life, followed by chapters that explore, in detailed historical context, her relationships (‘A Tough Broad’), her career as a playwright and screenwriter, the nature of her Jewishness, her politics, her careful stewardship of her fortune, the rise and fall of her celebrity in the 1960s and 1970s (‘Liar, Liar’), and the rapid deterioration of her image after her death.

There are many riches in this book, which is impeccably and sometimes obsessively researched and always written with great clarity. Although it is not a book for theatre historians, the meticulous chapter on Hellman’s earnings from her plays, and the way she turned these into a fortune, is full of information that is usually hard to find. The accounts of Hellman’s relationships, which went well beyond the one with Hammett that she mythologised, provide a rounded picture of the emotional life of a woman from that in-between cohort between the pioneering feminists of the early twentieth century and those of Kessler-Harris’s own generation. Her lifelong loving relationship with her first husband, Arthur Kober, and his second wife and children, is a revelation, as are her many serious affairs and warm friendships (often with former lovers). Her relationships, good and bad, with her household employees give us a glimpse of an aspect of the modern workforce that we often ignore.

But the great strength of this book is its analysis of the shifting political scene that surrounds this iconic twentieth-century woman and affects her life. Kessler-Harris seamlessly joins the politics of gender, economics, and ideology to convey how this ambitious and talented woman had to make her way through some of the greatest challenges faced by the United States during the twentieth century. She is particularly strong in analysing the ‘firestorm’ that followed Mary McCarthy’s notorious accusation on television that Hellman was an overrated writer whose ‘every word […] is a lie, including and and the’. Kessler-Harris manages to turn the unedifying sight of a catfight between two ageing divas into an absorbing discussion about the changing roles of women, debates over sexuality and the value of the nuclear family, escalation in the politics of anti-communism, the rise of identity politics, and the rise of celebrity culture.

A Difficult Woman is not a book to read through at a sitting. Readers will find themselves moving backwards and forwards, returning to it again and again, absorbing more detail with each reading. They may not come to like Hellman any better, but they will gain some understanding as to why this leading historian chose to spend ten years rewriting her story and her times.

Comments powered by CComment