- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Essay Collection

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: A dynamic collection

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Peter Robb, in this collection of some of his journalism, quotes E.M. Forster’s remark about Constantine Cavafy: that he lived ‘absolutely motionless at a slight angle to the universe’. That line is half true of Robb’s subjects in this book. They have a way of existing at an angle to the universe, but they are not at all motionless. The lives in this book have trajectories and velocities that bring out an equal dynamism in the man who recounts them, as could well be imagined by anyone who has read his earlier work about Italy and Brazil (2004) or his biography of Caravaggio (1998).

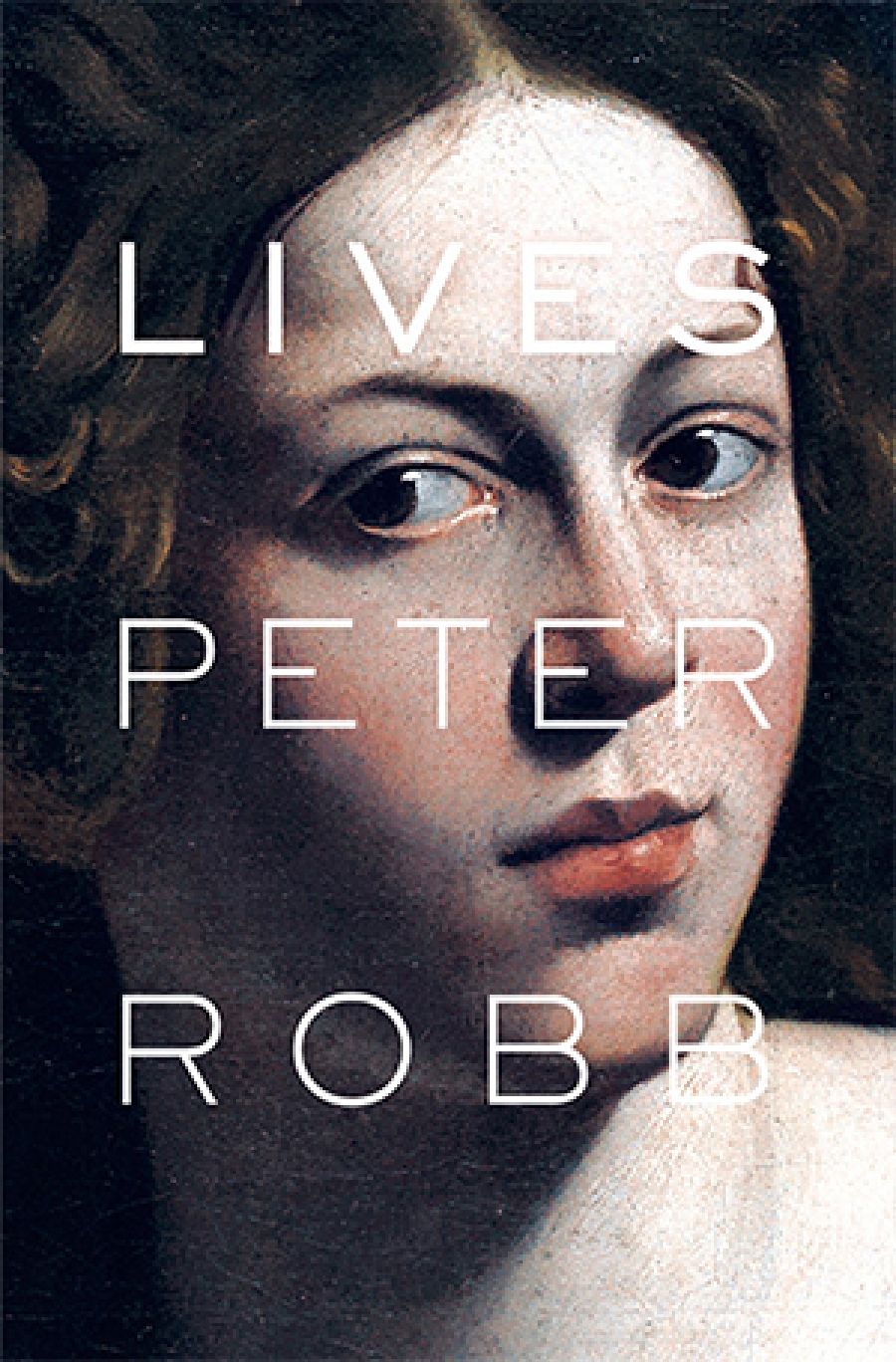

- Book 1 Title: Lives

- Book 1 Biblio: Black Inc., $32.95 hb, 398 pp

The book divides neatly into three parts: Australia, Italy, and Elsewhere. Brazil doesn’t make much of an appearance. This is surprising, given the knowledge and passion that Robb evinced in his book on the country. In Australia he profiles theatre directors Benedict Andrews and Lally Katz, and film director Ivan Sen; actor Alex Dimitriades; architect Glenn Murcutt. He reviews Julian Assange’s autobiography and brilliantly remarks that it shouldn’t have been ghosted by Andrew O’Hagan but by Peter Carey, ‘that specialist in Australian originals’. He attends the trial of Ivan Milat, and spends time in the Intensive Care Unit at Brisbane’s Prince Charles Hospital with its director, John McCarthy. He gives us pages from a 1996 diary, in which he casts an eye on his patch of Kings Cross, with Jilly from the deli and her run-ins with her daughter’s boyfriend’s mother; the poet with the tattooed neck; the yodelling country and western singer; and the Couple, two emissaries from the land of the Beautiful People who mysteriously come to live in Robb’s apartment block.

What puts these pieces above the run of journalistic profiles is the distinctiveness of the voice behind them.Though Robb never competes with his subjects for our attention, the insights come from someone who has obviously been around, but they always follow the contours of whatever he is writing about. Journal entries aside, the most piquantly self-referential moment comes at the end of his piece about fashion designer Akira Isogawa, when he says he wants to wear one of Isogawa’s dresses, and then describes in detail exactly which one (in photographs Robb by no means presents as feminine). This is a little delirious, but not comic or even very camp. ‘You have to be strong to be vulnerable,’ Robb says in his diary, and the self-assurance behind owning such cross-dressing reveries would have to be fairly high.

The vulnerability is most on show in the profile of Marcia Langton. Having appreciatively described what it seems inadequate to call her feistiness, Robb gives a scene in which he himself bears the brunt of her sudden rage. Over dinner she talks about how making money is a special gift, and then takes issue when he demurs from her regard for the super-rich. Robb, who has written with brio about the scrapes Caravaggio got into, evokes the drama of the quarrel, without sparing himself: ‘We returned to the cottage in silence. I was trembling and deadened but her eyes were now sparkling in the dark. She prowled the house and, seeing my weakened state, loosed a few more assaults, like a feral cat cuffing a wounded bilby to see if it offered any last sport. She questioned me on my sexual history as she never had before.’

Earlier in this profile, Robb says of Langton’s writings that ‘they have a fabulously demotic flair, at once cultivated and street smart’. The same goes for him, though there is little here to match the colloquialisms of his biography of Caravaggio (M: The Man Who Became Caravaggio) or its strategy of wresting him away from the mandarin formalities of art history, even if the same resolve not to be too precious in the vicinity of High Art comes through in the racy account of The Marble Faun: Or, The Romance of Monte Beni (1860),Nathaniel Hawthorne’s Gothic novel about Americans in Rome. Robb’s style is the product of a powerful engine over which he always has complete control.

Some of the pieces in the Italian section give different angles on material Robb has covered before. Caravaggio, or Merisi as he is here, makes a couple of appearances, in one case refracted through an essay about the distinguished Italian art historian Roberto Longhi, who more than anyone else recovered Caravaggio for our own time. The Sicilian writers Leonardo Sciascia and Giuseppe di Lampedusa are written about, as is Pier Paolo Pasolini’s unfinished, posthumously published novel Petrolio (1992), which gives Robb the opportunity to make a brisk summary of postwar Italian fiction. Robb himself amusingly turns up at Cinecittà in 1971 and talks his way onto the soundstage where Fellini is shooting his Roma (1972).

Another Italian essay – along with the diary the most humorous thing here – deals with Giovanni Comisso, a minor Italian writer of the earlier part of the twentieth century, and his travails with boys, rivals, and both world wars, the first of which gave him a lot of opportunities for nude bathing with his fellow soldiers. Comisso’s parade of lower-class love objects and his friendship with the even more flamboyant and solipsistic painter Filippo de Pisis make for absurd reading, though not just that. Robb combines a mordant, though subdued, sense of the ridiculous with sympathy for the way de Pisis pursued his obdurate sense of himself: he admires people who don’t spend their lives looking over their shoulders.

He is also drawn to people who take the long way round. Marcia Langton’s journey from a hard childhood, and her travels in Asia and America in the early 1970s, her chequered career in and about academia: all these find a rhyme in the adventurous life of Glenn Murcutt Sr, who took his family to Papua New Guinea between the wars and mined gold there, and who also took them on a road trip across Roosevelt’s America. These displacements are at their purest in the short essay about dancer Margaret Scott, who, with the Ballet Rambert, entertained the troops in the ruins of Berlin at the end of World War II. The piece seems to consist almost entirely of juxtapositions, weird situations: the ballet company in a fog-bound ferry adrift on the English Channel, or Scott and a British officer friend in the ruins of the Reich chancellery. These itineraries make excellent copy, and reveal how good Robb is at thinking his way into the contingent and particoloured experiences that make a person.

Robb finds side streets – and conflict – in some unexpected subjects. In the last section, along with pieces about Gore Vidal, Gary Gilmore – the high and the low – and a review of the biography of Rimbaud by Graham Robb, there is a curious piece about two linguists, Michael Halliday and Bill Foley, who didn’t sign up for the orthodoxy that Noam Chomsky – not always, according to them, with the highest intellectual scruples – imposed on their field. Part of Robb’s own itinerary is sketched in as the ground bass to a memoir of some English literature scholars he has known, who suggest the lives he himself might have led.

Bruce Chatwin once boasted that a woman wrote to him to say his books had helped her to overcome a depressive illness. Peter Robb’s writings, with their curiosity and implicit compassion, their fierce, managed energy of style and sensitivity to the energies of character, have the same invigorating effect. Even in the Intensive Care Unit, he finds that the hilarity of the nurses, the wild joking of McCarthy with anyone who was in a position to respond, especially the distraught families, the presence of children, the edge and clarity everything acquired in the face of death, all lent a kind of Mozartian gaiety to the collective life that was streaming through this theatre. For the last phrase read: the collective life that streams through the theatre of this book.

Comments powered by CComment