- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Commentary

- Custom Article Title: Patrick White in Adelaide

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Patrick White in Adelaide

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

By the time I found him twenty-five years ago in the Adelaide Hills, Glen McBride was old, tiny, spry, and ready to boast about his career. I doubt many readers have heard of this little man or know of his pivotal role in the literature of this country. That’s what had me knocking at his door. And though he disowned none of it in the hours we spent ranging over his life and times, what really perked him up was confessing his part in the salami and sausage business in that part of the world.

It seems that as a sideline during the long years he ran vaudeville troupes and picture shows in Adelaide, McBride imported stuff called AV80 that made devon, sausages, and salami absorb something like their own weight in water. ‘Woolworths bought it by the ton,’ he told me with amusement not entirely masking his pride. ‘I am the man who ruined smallgoods in South Australia.’

McBride was also the man used by the governors of the Adelaide Festival to impose their will on the city’s literary types who had recommended unanimously that the festival of 1962 present Patrick White’s The Ham Funeral. McBride was a powerful functionary in an emblematic culture skirmish in Adelaide – and in this country – between old and new, foreign and home-grown, the arts and respectability, taste and power.

This is the centenary of White’s birth and roughly the half-centenary of the rejection of this by-no-means perfect play, which enjoyed a nearly perfect production, and a sold-out season, during the recent Adelaide Festival. The story of the rejection has been told many times, at first in anger and disbelief, later as a comic tale about the habits of an arrogant country town and the big men who ran it in those far-off days.

I have told the story that way myself, but opening up the boxes and going through my papers again in the last few weeks, I’ve begun to wonder how smug we should be about that contest in Adelaide, when clashes of this kind still break out in Australia and artists find themselves too often at loggerheads with politicians and the massed ranks of respectability. It’s enough to say Bill Henson’s name to be reminded that we haven’t yet done with ancient squabbles in this country between taste and power.

White wrote The Ham Funeral in a boarding house in London in 1947 while waiting for a boat to take him and his dogs to Australia. In the bravest act of his life – as writers, composers, and window dressers were fleeing Australia – White was going home. He was breaking with England much as the dreamy young man of the action was breaking out of the ‘great, damp, crumbling house’ where he lodged with Mrs Lusty. I like to think that when that pale kid finally reaches the front door after a couple of hours of vaudeville and Wedekind, he’s on his way to Southampton and a P&O boat to Sydney.

White tried and failed to sell the play for ten years. London wouldn’t take it. New York wouldn’t take it. Even Doris Fitton’s Independent Theatre Company in North Sydney wouldn’t take The Ham Funeral. And it might have stayed that way, and one of the great novelists of his generation might have given up his ambitions for the theatre, but for Adelaide. Those of his admirers who deplored White’s excursions into theatre – the chief of whom was his partner, Manoly Lascaris, who saw the theatre as a ‘virus’ infecting White’s life – wonder how many more great novels there might have been in the 1960s and the 1980s if it weren’t for White slipping Geoffrey Dutton and his friends on the drama committee of the Adelaide Festival a copy of The Ham Funeral.

White knew Adelaide a little. He saw it first as a schoolboy when the boat to England tied up at Port Adelaide in 1925. Several times over the next couple of decades, coming or going to England, White would dash into town, perhaps for a quick lunch at the South before his ship sailed again. Then in 1955, just after he had sent the manuscript of The Tree of Man to his New York publisher, White was battered by one of the most violent asthma attacks of his life and went over to Adelaide hoping for relief. Adelaide, he told his publisher, ‘has a dry, blazing heat which could clean out my breathing apparatus’.

I know nothing about that visit. I don’t know where he stayed or who he saw or even how long he was there. But there were stray remarks in letters about finding a ‘civilised oasis’ where he might live. ‘One feels happy just walking about the streets.’ But an old Romanian crank in his home town and then the new wonder drug cortisone came along to make life bearable for severe asthmatics in Sydney’s steamy heat.

Cortisone was working its magic by 1958 when Dutton insinuated himself, with great charm and purpose, into White’s life. Dutton was beautiful, gifted, charming, and part of the world of the bush that White mocked but trusted. Indeed, for years the two men thought their families were linked by the marriage of distant cousins. And it did not grate on White – or not for years – that this young man had introduced himself by letter as perhaps the only other of the rare Australian species of aristocrat writer.

Adelaide’s shaping role in Patrick White’s career began here, not with a play but with an essay called ‘Prodigal Son’, written by White for Dutton’s magazine Australian Letters. Nothing he ever wrote has been so often quoted in the years since as this cry from the depths. You know the words:

In all directions stretched the Great Australian Emptiness, in which the mind is the least of possessions, in which the rich man is the important man, in which the schoolmaster and the journalist rule what intellectual roost there is, in which beautiful youths and girls stare at life through blind blue eyes …

‘Prodigal Son’ is remembered as a great complaint. It is. But that’s unfair to its bigger purpose. It is an artist’s confession that, for all he despised – and would go on despising – about this country, he knew he was bound to it for life. For White there could be no escape.

The two men eventually met in Sydney in October 1960. By this time Dutton had been commissioned to write a little booklet about White for the Lansdowne Press. But he had come over to Sydney with another more urgent mission. Adelaide’s answer to the Edinburgh Festival was after a new Australian play. The inaugural festival had seen Alan Seymour’s The One Day of the Year rejected by the governors for casting a slur on the fine men who had gone abroad to fight in the war. Now a rather desperate hunt was being conducted by the festival’s drama committee to find a fresh Australian play for the second festival in 1962. Dutton’s real mission in Sydney was to winkle out of White a copy of a play he had mentioned a couple of years before.

White was toying with Dutton as he tried to sell a slightly rejigged version of the play in New York and London. After all, he was no longer the promising modernist who had failed to find a producer for The Ham Funeral in the late 1940s. He was the acclaimed author of The Tree of Man (1955) and Voss (1957). Managements were fascinated, curious, and disappointed. When all their rejections were in and there was finally no hope of a production in the West End or on Broadway, White ‘unearthed’ a copy and sent it off to Dutton. He and his friends on the committee were besotted. To a man, they backed The Ham Funeral for 1962.

All was going well until the festival governors got wind of the foetus in the bin. You remember the scene: on the way to collect the dead landlord’s relatives for the slap-up wake, the pale young man comes across a couple of music hall ladies in the street rifling through a garbage bin where, to their horror, they glimpse a foetus. The ladies flee, leaving the young man to deliver the famous lines:

No angel struck you on the mouth, to silence what you already knew. Your love returned to love, without ever feeling the thumbscrew and the rack. Tender, humorous foetus …

The foetus was at the heart of the ugly farce that followed. Those knighted governors – the brewers, generals, bankers, and newspapermen of Adelaide – called for the script and were horrified. They did not want this play. They were not going to put their reputations – and the reputation of their virtuous city – on the line by allowing filth of this kind to be performed. Not that they admitted the problem was a taint of abortion in act one. They declared the issue here was maintaining appropriate standards.

‘I would like to emphasise one principle: the standard of the thing,’ said Major General Ronald Hopkins, the festival’s administrator, when issuing his earliest riding instructions to the drama committee. ‘We have got to be very clear that everything is world standard and international standard. That is acceptable anywhere.’ The governors didn’t have a clue what was really happening in theatre in America and Europe. All they saw were productions imported and trucked around the country by the Australian Elizabethan Theatre Trust and J.C. Williamson. But the big men of Adelaide knew one thing in their hearts: that respectability was a passport to acceptance everywhere. And The Ham Funeral wasn’t respectable.

They had suffered for their candour when rejecting The One Day of the Year on patriotic grounds, so the governors were determined to find artistic reasons to reject White’s play. ‘They were in a field where they had to be very careful,’ Hopkins told me. ‘Lack of professionalism in the arts was a very serious problem.’ So they called in Glen McBride, who was running the fifty-six picture shows in South Australia and western New South Wales owned by the Waterman brothers, governors of the festival. He also advised the Australian Elizabethan Theatre Trust on suitable shows to tour through the state. When we met years later, McBride was happy to tell me first that the foetus was the real problem here and, second, that the only theatrical expertise he claimed was commercial. ‘I have a feeling for it, a nose,’ he said. ‘I’m not artistic.’

Starting with McBride, the governors imposed on the drama committee a number of figures hostile to the play until they could declare it irrevocably split, intervene, and resolve the ‘impasse’ by rejecting the play. Performed in its place would be George Bernard Shaw’s Saint Joan, Ben Jonson’s Volpone (with a young Kamahl in the cast), and a fashionable but now entirely forgotten verse play from America on the trials of Job. It was small-town politics of the most naked kind. The governors had imposed their taste. These were, after all, men who enjoyed an unbroken record of getting their way.

Had The Ham Funeral never been performed or had it been performed to a ho-hum response, White might have put his theatrical ambitions behind him. But along came Adelaide first to raise and then to dash his hopes. At first he pretended he didn’t give a damn, but after a few weeks he confessed to Dutton: ‘I find, after all, I got rather a battering over The Ham Funeral. My final reaction has been to sit down on May Day and start a new play, the first for fourteen years. The last two days it has been pouring out in almost an alarming way, and will probably shock more than the Funeral, as this one is purely Australian, and at the same time has burst right out of the prescribed four walls of Australian social realism. If I don’t get this one on, and twist the tails of all the Adelaide aldermen, Elizabethan hack producers and old maids dabbling in the Sydney theatre, I shall just about bust. The new one, by the way, is called The Season at Sarsaparilla …’

This time he was working on a masterpiece.

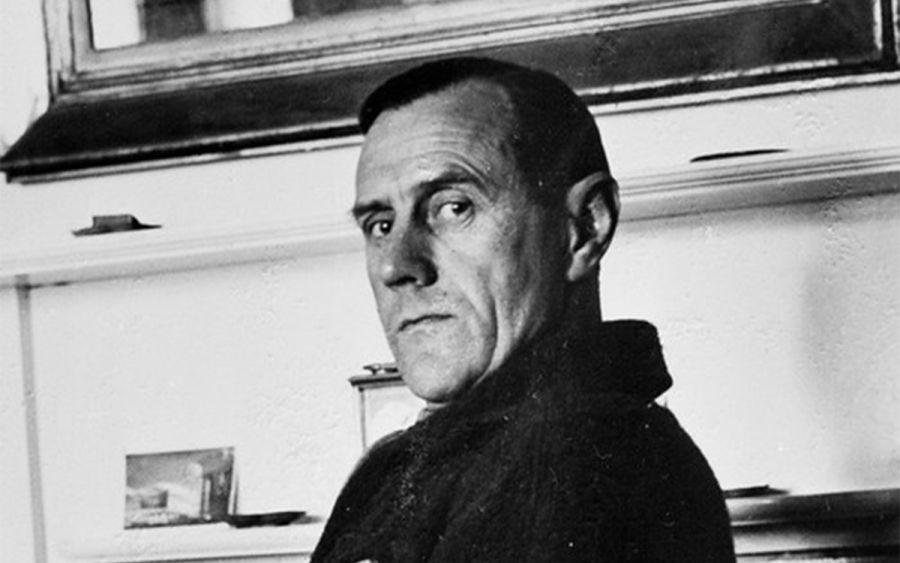

Australian Book Review June–July 2002. Photograph: Axel Poignant, Patrick White and his Cat Tom Jones c. 1956, National Library of Australia

Australian Book Review June–July 2002. Photograph: Axel Poignant, Patrick White and his Cat Tom Jones c. 1956, National Library of Australia

Maybe it’s too late to destroy the great myth of Patrick White’s life that all Adelaide ever did was thwart him. But, in his centenary year, I’m giving it a go. Yes, Adelaide dealt him an embarrassing blow. But that blow made him the playwright he had wanted to be all his life. He was not a novelist with a bit of a hankering to write for the theatre. He wasn’t another Henry James. Being a playwright was his fundamental ambition. We can now read, in the National Library of Australia, the notebooks he kept in the 1930s when he began writing in London, and they are full of sketches for plays. Not novels but plays. But it was Adelaide – not London or New York – that made a furious and rather humiliated Patrick White a playwright and nudged Australian literature in a new direction.

Such a divided town: on one side were those whom White called ‘the semi-literate race of generals and editors’. On the other were the Duttons, Max Harris in his best days, and the Adelaide University Theatre Guild led by the young scientist Harry Medlin, which had The Ham Funeral on stage within months of its rejection.

In November 1961, not far short of his fiftieth birthday, White came over to Adelaide and, for the first time in his life, saw one of his plays performed. He was captivated. Theatre had him in its grip again. He wrote to an old quean in the bush: ‘It was wonderful the way everything went right after fourteen years of waiting, and so many attempts to prevent the play coming to life.’

This was more than a triumph for White. The controversy over The Ham Funeral had drawn in many Australians who were hardly interested in the theatre. The whole Adelaide fracas had become a rallying point for those who were unhappy with the boring, official culture of Australia in the late 1950s and early 1960s, and hated the philistine power of the Establishment to determine what was written, seen, and read in a country where books, films, and plays continued to be heavily censored and banned.

But let’s be clear about this: White hadn’t declared war on the entire Establishment. When he came over for The Ham Funeral, he stayed in the hills with the Duttons and went with them to Anlaby, their home territory, where he met the ferocious and theatrical old Mrs Dutton, who joined the bestiary of grand dames in his life and work, the parade of wilful rich females that had begun with his mother. Despite its torments, he loved Adelaide. ‘The vibrations are right,’ he wrote to old friends in Sydney. ‘It is peaceful and civilised. A wonderful market full of wurst, cheeses, herbs, fresh fruit and vegetables.’ He began to refer to Adelaide as his favourite Australian city and thought seriously of moving there to live. But Manoly Lascaris was sceptical. ‘Patrick,’ he said, ‘we cannot live in Adelaide. There are not enough people for you to quarrel with.’

The Season at Sarsaparilla was another triumph at its première in the Guild Theatre in September 1962. Note to program writers: it was neither offered to nor rejected by the Adelaide Festival. One of the finest plays in the repertoire of Australian theatre was written for, and premièred by, the Adelaide University Theatre Guild. It went on to be performed everywhere in Australia. It remains a standing challenge to anyone aspiring to be a great director in this country. Jim Sharman, Neil Armfield, and Benedict Andrews have shown what they are and could be by conquering The Season at Sarsaparilla.

The state governor, Sir Edric Montagne Bastyan, was there on the first night. White loved that, but refused to wear evening dress. ‘I have a dinner jacket somewhere,’ he said. ‘But moths have turned it into lace.’ The season sold out. White was telling friends that he had four more plays in his head waiting to be written. The first was an adaptation of his short story ‘A Cheery Soul’, written for John Sumner of the MTC. Medlin and the Guild turned it down, which hurt White but did not lead to a breach. Then, on the way back from what was now an annual holiday with the Duttons at their place on Kangaroo Island, White stayed in Adelaide for a few days in early 1963 to give Max Harris and Harry Medlin the script of the next play, Night on Bald Mountain.

They all hoped this would be the one the festival accepted. But the governors and Glen McBride had other ideas. McBride fought this ‘dreary’ play with all the unyielding hostility he brought to the battle against The Ham Funeral. Survivors from that time told me that behind closed doors at the town hall there raged terrifying arguments. The governors again crushed the experts of the festival’s drama committee. But Medlin and the Guild retaliated by refusing to allow the festival to use their theatre in 1964. It was a brave act against powerful figures in an unforgiving town. The Guild decided, come what may, to stage its own production of Night on Bald Mountain during the 1964 festival.

White came over alone for the last fortnight of rehearsals. This time he didn’t stay with the Duttons, but at Scotty’s Motel in North Adelaide. During breaks in rehearsals he cautiously explored an Adelaide Festival for the first time. In the bar of the South he met the Duttons, the Nolans, and the Haywards. He wrote to friends: ‘I carefully avoided Writers Week which began a couple of days before I left.’ Before flying out, he did a big shop at the markets – wurst, Mt Lofty ricotta, yabbies, and squid, but, unfortunately, no eels – and had lunch in the stronghold of the opposition, the Adelaide Club, with – he told his New York publisher – ‘two of the more liberal festival governors in the party and numbers of the dying elephants looking on’.

Night on Bald Mountain marked a full stop. Most of the reviewers weren’t unkind, but I suspect White knew the play was weak. It has hardly ever been performed again, though in 1996 Neil Armfield revived it brilliantly at Belvoir. But the key to White’s putting aside his theatrical ambitions was his falling out with John Tasker, the young director he had chosen for Ham Funeral, Sarsaparilla, and Bald Mountain. Theirs had been almost a love affair, and it was over. White was as fed up with fighting ‘Tilly’ Tasker as he was with battling the burghers of Adelaide.

I’m not sure he set foot in Adelaide again for over a decade, except to fly back and forth a few times to Kangaroo Island. He never lost sight of what was good about the city and never forgave the bad. ‘One is inclined to think of the Adelaidians as being advanced because of a handful of progressive intellectuals one knows,’ he told his rather starry-eyed English publishers, who were thinking of launching in that city Philip Roth’s mad, dirty, and wonderful novel Portnoy’s Complaint (1969). ‘But the majority are terribly starchy and reactionary. Sydney is the most emancipated city in Australia; I’m not saying that because I come from it; there is much that I detest about it. On the other hand, I’d like to see Portnoy come in the Adelaide Establishment’s eye!’

That might have been it for White and theatre. The next fifteen years were spent doing what he did best, writing novels: The Solid Mandala (1966), The Vivisector (1970), The Eye of the Storm (1973), A Fringe of Leaves (1976),and The Twyborn Affair (1979). He would write nothing more on that scale. He was in his late sixties by then and growing frail. He had been caught up in political agitation to save the planet from nuclear Armageddon. But these weren’t the real reasons he never finished another big novel. Jim Sharman and Adelaide must take a lion’s share of the blame.

Sharman, the wunderkind of 1970s musicals, came home to Australia and brought theatre back into White’s life. After a superb production of Benjamin Britten’s Death in Venice at the 1980 festival – which White went over to see – Sharman was appointed the festival’s next artistic director. In early 1981, when White was hard at work on his next novel, Sharman asked him for a play to open the 1982 festival. Production guaranteed. No ifs and buts this time. For a few weeks White juggled both projects, then put aside the novel to write Signal Driver.

My gratitude for Signal Driver – which I believe is a play of wisdom and mystery – took a serious blow four years ago when I had a chance to sit with White’s papers in the National Library. These are the papers his literary executor Barbara Mobbs had refused to burn. I’d helped the librarians sort them when they arrived, but I hadn’t had the opportunity to dig down into them until The Monthly commissioned me in early 2008 to go to Canberra and write about the papers. There I found what Sharman and Adelaide had broken off: the first third of novel called The Hanging Garden.

I began to read that pile of badly written foolscap merely with curiosity. Almost without my realising, I found I was reading with all the excitement we feel when we have a good book in our hands. And it got better. I was not far in when I discovered I was reading a masterpiece in the making, the story of two children sent across the world to shelter in a garden on Sydney Harbour during the war. The story breaks off on VE day in May 1945. All that he wrote of the Hanging Garden has now been published as a sort of novella of 45,000 words after lying in the dark for thirty years. Now we can see Signal Driver for what it is: consolation of a kind for a fine novel lost.

The play’s title presented a last minute problem. ‘Signal driver’ is the order written on bus stops in New South Wales, but South Australia uses the splendid, almost courtly rhetoric of ‘hail bus here’. This cultural divide threatened a rich source of misunderstanding. Should the title be changed to fit the city? No, said White. The title would remain as it was with the emphasis falling on ‘signal’ not ‘driver’. Impossible.

White’s relations with the Duttons had frayed. When he came over for the last couple of weeks of rehearsals, he stayed not with them but with his protégé, his delight, the star of his show, Kerry Walker, in her house in Myrtlebank. Not knowing quite what her standards of housekeeping were, he brought with him some new dishcloths and six packets of Curly Girl stainless-steel pot scourers, which he considered indispensable in an orderly kitchen. He shopped. He washed up. He fed the cat.

Neil Armfield was the director and welcomed White to rehearsals, where he sat quietly, occasionally filling a lull with a wry comment. He loved it. ‘Working with the actors on Signal Driver I learnt a lot more about theatre, and was able to explain a lot to them,’ he told David Malouf. ‘In the past my presence wasn’t exactly encouraged.’ He sent postcards to friends confessing: ‘It tears me to bits, so much of our life in it, and I cry all through Act III, which becomes embarrassing.’

After morning rehearsals, he sometimes slipped over to the Adelaide Railway Station for lunch. Sharman found him there one day and wrote in his memoirs Blood and Tinsel (2008): ‘I was in bustling festival director mode and was surprised to encounter him incognito among itinerants on a train station bench, munching his lunch. He looked up wearily: “I’m just an old man eating a pie … leave me be.”’

White was the totem of the 1982 festival. His face was everywhere in the city. But there are no reports of him celebrating, in any sense, his triumph over the governors after so many years. They and their lackeys suffered in White’s imagination a worse fate than being defeated. They were forgotten. What excited him was to be at a festival offering this country what had never been experienced here before: Janáček, Pina Bausch, Edward Hopper – and Signal Driver. On the opening night, White took a bow and congratulated Adelaide on having Sharman. The play was not particularly well received by the critics. They were far more interested in the performance of the garden scene from the opera of Voss, with libretto by David Malouf and music by Richard Meale. White thought it not ‘austere and gritty’ enough. He was getting something like Richard Strauss and wanted the harshest Schoenberg.

Two more plays followed, both written for Adelaide. The first was Netherwood, a rather mad piece, which Sharman directed in 1983 for his Lighthouse Company at the Festival Theatre. Then came Shepherd on the Rocks, written for another of the actors he loved, John Gaden, who at that time was artistic director of the State Theatre Company. It was a sort of mystical revue based loosely on the story of the Vicar of Stiffkey, who became a circus performer until one of his lions ate him.

I was there on opening night in 1987 and saw White take a bow with the cast, a bent, soft little figure with huge ears, carrying his stick and an envelope on which he’d jotted a few things to say. There was a tumult of applause, which he silenced with big sweeps of his free hand. He was pleased, he said, to be facing an Adelaide audience again. He urged people to tell their friends to come: ‘Delay is death in the theatre.’ He was the last to leave the stage, looking back over his shoulder like a kid at a school play, hesitating at the wings before disappearing.

There were no more plays. He had only a couple of years to live. Armfield says Shepherd on the Rocks was very consciously White’s farewell to the theatre. Danny Shepherd, the fallen priest, might be White’s Prospero saying goodbye to his audience:

Are you for magic? I am. Inadmissible when we are taught to believe in science or nothing. Nothing is better. Science may explode in our faces. So I am for magic. For dream. For love […] at the gates of death – which is not hell, as church voices have so often promised, I hope to shed my doubts, fears, obstinacy, lust. Do not expect an easy transition. I believe that renewal can only be reached through blood and ash. While many of us will continue pursuing false dreams – that’s where the votes are to be caught (all you need is a shrimping net and a fair measure of hypocrisy). I pray for grace – for the deceived shrimps – the monsters of power – and the least deserving creature – myself.

Comments powered by CComment