- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Media

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Newspapers, they say, are in the throes of ‘far-reaching structural change’, a euphemism for ‘extinction’ that arouses complacency in the breasts of the e-literate; fury in those of the technophobes. But one only has to take a slightly longer view to realise that the golden age of newspapers, over which Creighton Burns presided as editor of The Age, may have only ever been a transitory phase.

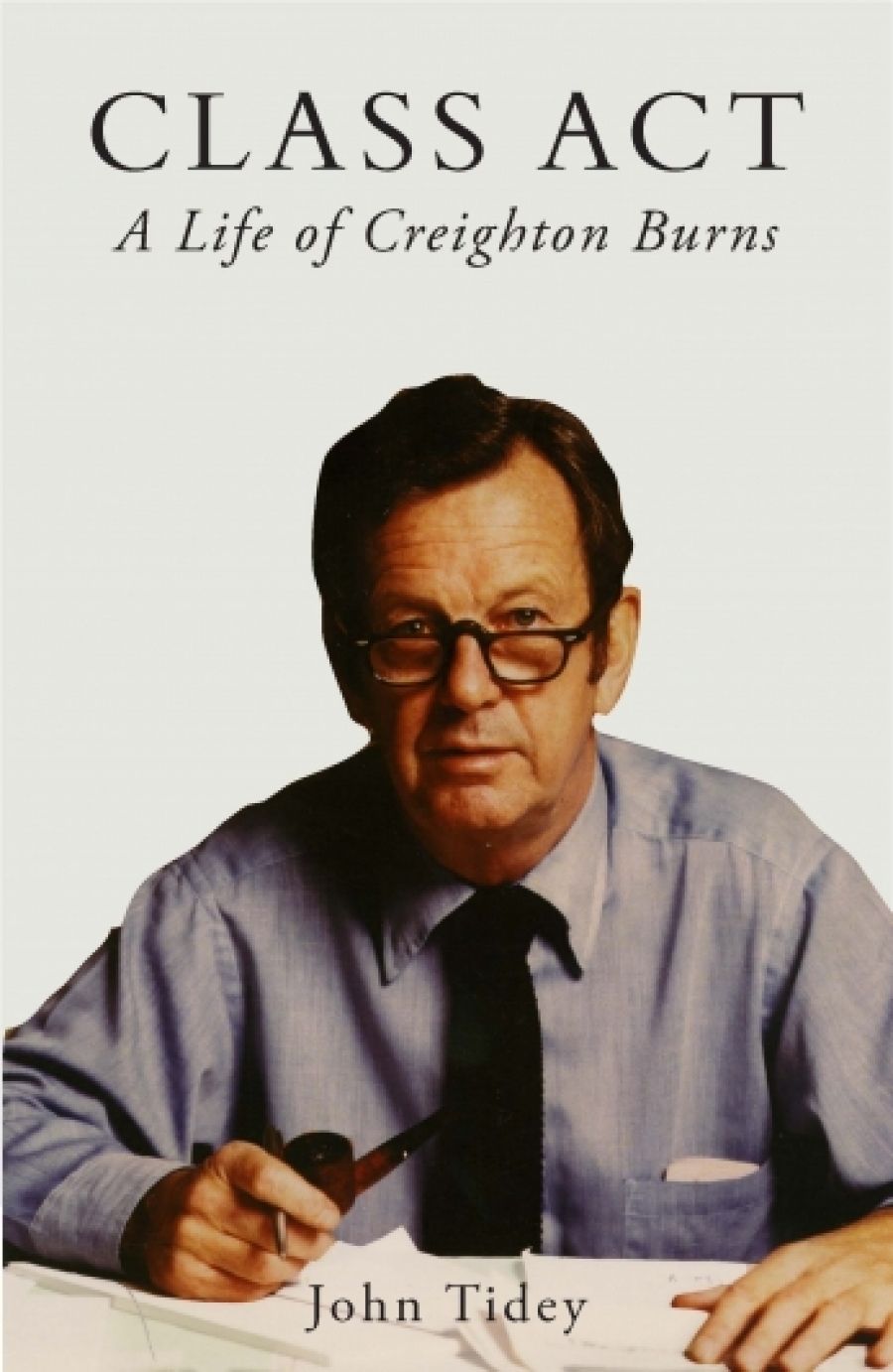

- Book 1 Title: Class Act

- Book 1 Subtitle: A Life of Creighton Burns

- Book 1 Biblio: Australian Scholarly Publishing, $34.95 pb, 194 pp, 9781921509496

Burns was born in 1925, two years after the inception of radio broadcasting in Australia. John Tidey tells us he was a ‘technophobe’, but this was obviously a selective trait; when television was introduced, Burns, then in his early thirties, seized on the new medium. The circulation of The Age peaked on his watch as editor, when he was in his late fifties, and he retired well before the current predicament of newspapers became apparent. Tidey’s biography reminds us just how radically the media landscape has changed in just one lifetime.

Burns was spared the full horrors of the ‘social’ media, a world in which even the pope has a Twitter account. But his successors in today’s editorial offices don’t have the option of technophobia. Instead, they talk the e-talk, which at times makes them sound like aristocrats arguing cogently for cheaper, more effective guillotines.

To the e-literate the triumph of the new media, which abolishes the distinction between journalism and word of mouth, is a clear case of a better mousetrap. It shifts attention from the ‘content provider’, as journalists are now known, to the consumer – as the reader should properly be thought of. The lucrative ‘cross-platform synergies’ linking the e-media to its nerdy printed sibling, the quickie thrill of the 140-character ejaculation: these have brought Warhol’s dictum about fifteen minutes of fame closer to actuality. It really is all about Me.

For example, one of the biggest stories in the wake of the American raid that killed Osama bin Laden was that of the Blogger of Abbottabad. He wasn’t involved, didn’t get hurt or anything – he was just there, blogging away – the anonymous observer who was just like one of us. And he was huge news: the universal reaction of e-literates to the demise of bin Laden, the Ogre of The Age, was ‘Hey, what about that blogger?’ Thus the whole impact of the story was significantly diluted by a sideshow – very conveniently for anyone who might have wished to downplay the raid – which was, after all, an act of war on the territory of a US ally.

To those looking for evidence that news has become less interesting and more superficial since Burns’s day, the Blogger of Abbottabad seems like Exhibit A. But the question is a complex one of cause and effect, and involves subjective judgements about what constitutes ‘interesting’. Depending on who says it – depending on who owns the medium – ‘interesting’ can just mean ‘whatever sells’. And it has long been a cardinal principle of the industry that you don’t sell newspapers by telling people things that they don’t know, but rather by reassuring them that the way they already think is right.

So the suspicion arises that it is not so much the newspapers as the ‘consumers’ themselves who have become less interesting: our judgement has become so banalised by the torrents of junk information deluging the public consciousness that we really are now fit only for celebrity gossip.

However much one may suspect it, though, it is hard to prove that journalism was more thoughtful in Burns’s day. Clouding the issue, Burns was actually a product of pre-Whitlam Australia, itself long derided as a byword for superficiality: a land asleep, a kind of intellectual Narnia under the sway of the White Witch Menzies, awaiting the Labor Aslan to bring it to life. If this was so, how can things have worsened since then?

Burns’s output as The Age’s South-East Asia, then defence, correspondent in the era of the Vietnam War suggests that this was not the case, that mediocrity was not his milieu. His reports on the Vietnam War were sufficiently authoritative to become a standard source, still quoted, for example, in Ashley Ekins’s Fighting to the Finish: The Australian Army and the Vietnam War 1968–1975 (2012). In his analysis, Burns was critical of Canberra’s attempt to portray Australian participation as an outstanding success in one small area – the province of Phuoc Tuy – while ignoring the fact that overall the war was a débâcle. One wonders how many of his successors will make the same point about the Afghan province of Oruzgan.

If, in light of the triumphant progress of the e-media, Tidey’s book seems like an elegy for a bygone age, then that’s exactly what it is. While he does stop this side of hagiography, Tidey’s attitude towards his subject is frankly one of affectionate admiration for the man and nostalgia for his times. Burns comes across as a decent bloke, highly intelligent, who did a great job and (largely) had a good time. And although Burns may not have intended it, he certainly wound up as one of the Great and the Good.

It therefore seems sacrilegious to say so, but Burns and the journalistic culture he fostered attached undue emphasis to politicians – not to politics, but politicians. And although politicians would dispute this, the two are not synonymous. Burns studied political science in its early days as an academic discipline, and was a pioneer psephologist and a self-confessed ‘political voyeur’. That’s fine, but why should these avowedly personal interests have become compulsory for everyone? Because that is what editors do: they impose their interests on their audience. It is no accident that the media’s fascination for politicians and their faux-gladiatorial antics resembles another smothering weed of Australian public life: the obsession with sport. And this comes at a cost. If a newspaper runs big on any one story, it is ignoring another. And if a newspaper – as they all do – is perpetually running stories about politicians, it is perpetually ignoring other stories.

The answer to this charge is that ‘politics is important’. Well, yes, political outcomes are of course important, but by what stretch of the imagination does this importance extend to Julia Gillard’s shoe? Just why do those hardy perennials of factional struggle and leadership tension constitute the pivot on which the universe turns?

When Burns was a boy, people would queue up in the street to buy a daily newspaper. By the end of his life, they were being given away to shore up circulation. This is not because people have become too poor or too rushed to buy and read them. As a matter of fact, Australians have been turning into a nation of café dwellers at the very same time as they have been abandoning newspapers, previously the boulevardier’s indispensable companion. The same people who carry their laptop everywhere and sit down for several $4 cups of coffee a day won’t buy newspapers because ‘they haven’t got the time or the money’ – which is clearly nonsense. They just don’t feel like it. Perhaps they’re sick of politicians.

Comments powered by CComment