- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

I once had a vague fantasy that Martin Amis and I should get married. He was cool and handsome, and we had so much in common. We were about the same age; we had both read English at Oxford. My father worked as a cartoonist at the New Statesman when Martin was literary editor. I was mad about books and writing; Martin, in his early twenties, was already a famous novelist. Perfect match.

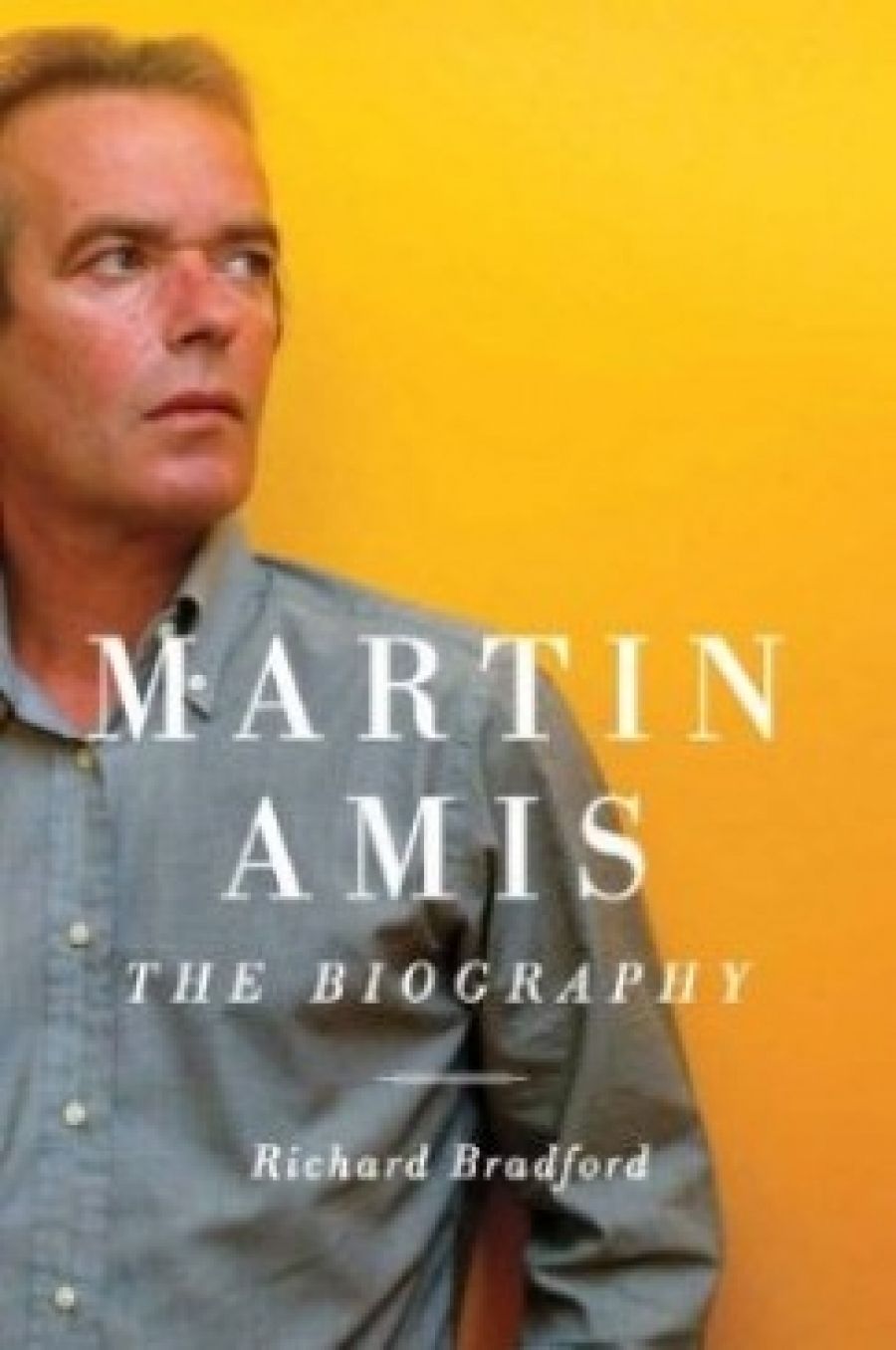

- Book 1 Title: Martin Amis

- Book 1 Subtitle: The Biography

- Book 1 Biblio: Constable, $34.99 hb, 440 pp, 9781849017015

Reading Richard Bradford’s hefty biography, I discovered more connections. I knew one or two of the girls who went out with Martin. I might have bought the odd record from him at his uncle’s shop in Rickmansworth. At the age of thirteen, we both helped to push our respective broken-down family cars over the Pyrénées to Perpignan. Spooky?

Alas, our union was not to be for all sorts of reasons, but mainly because we never met or had any kind of contact at all. If we had, Martin would have very quickly spotted my shortcomings, and I would have very quickly spotted that he was short. Anyway, Bradford has persuaded me that we probably both had a lucky escape. Not, mind you, that he isn’t nice about Martin (we both call him that to distinguish him from father Kingsley). Quite the opposite. This is an authorised biography in the sense that Martin cooperated fully. His quotes are included from long conversations. The book is called Martin Amis: The Biography. Like Winnie The Pooh, such a title suggests that no other variation should be countenanced.

Bradford, a veteran of twenty books, including a biography of Kingsley (2007), tells us that he decided to write about the man and the work after he saw a guy reading Money (1984) on a plane and shaking with suppressed, embarrassed laughter. He’s not exactly a hagiographer, more a vigorous defender. That means he has to set up Martin as the constant butt of attack, which is not hard.

First, there is Martin the media star, the tabloid version of the writer, who is (as Kingsley would put it, albeit affectionately) a little shit. He slouches elegantly through the London and New York literary scenes, cigarette dangling from his contemptuous lips. He beds a string of beautiful girlfriends and dumps them all. He marries a beautiful woman, has two children, then dumps her. He marries another beautiful woman, has two more children. He dumps his literary agent, who is married to one of his best friends. He is paid much more money than a literary writer should ever receive, and he spends far too much of it on his teeth.

Salman Rushdie and Martin Amis, 1995

Salman Rushdie and Martin Amis, 1995

Bradford doesn’t have too much trouble showing us that this vapid Mick Jagger creature is a myth. Next, he wants to persuade us just how good a writer Martin is. And no, says Bradford, he’s not just a pretty stylist. Words such as ‘brilliant’ and ‘genius’ crop up quite a bit in his analyses of the books, even the notoriously panned Yellow Dog (2003). Bradford attributes the critical attacks to insecurity, envy, and moral squeamishness. By the time we get to the last chapter, ‘Significance: Is He A Great Writer?’, we know exactly what the answer will be.

When it comes to Martin’s politics, Bradford seems more equivocal, but still very much on the defensive. In middle age, once Martin had children to protect, the world became a dangerous place. His stance shifted from amused indifference to almost obsessive horror: in turn, he used fiction (and sometimes non-fiction) to wrestle with the nuclear arms race, Nazi war crimes, Stalin’s genocide, and Islamic terrorism. Bradford doggedly takes us through the smoke and shrapnel of the salvos that Martin drew from various sections of the intelligentsia; and again, though he seems a little unimpressed by the nuclear protest book Einstein’s Monsters (1987), he is unswervingly on Martin’s side.

It was at about this point, more than two hundred pages into the book, and almost in spite of Bradford, that I started to like Martin. Our biographer, I felt, had been protesting too much: he had a way of putting any faint signs of weakness from Martin down to false modesty. When Martin confesses to ‘crying jags’ during his time at Oxford, for example, Bradford prefers the image of the confident, louche undergraduate marked out for a bright future. Too many things, from Martin’s somewhat haphazard upbringing to his parents’ divorce, seemed to be sliding off the duck’s back. He seemed precocious, smug, unfeeling. He was like one of those Shakespearean villains who observe the action from the sidelines. We expect a sardonic soliloquy, but we never get one – except in Martin’s books.

What was going on? What was Martin really like? At least by the book’s halfway mark, he knew something personal about trauma and had a conscience, but where had these things come from? Not out of the blue, surely. I kept going, but it didn’t get easier.

There is no shortage of detail from the ever-thorough Bradford, and the quotes from Martin’s friends and family can be illuminating – the late Christopher Hitchens, in particular, is always a goldmine, even at moments when he fell out with his friend. But I felt I didn’t have a sense of a whole person. Maybe it’s all those years of having to deal with the media, but Martin armour-plates his privacy – his own quotes are surprisingly unrevealing – and Bradford’s awe constantly gets in the way.

Curiosity about Martin pulled me through this book, but Bradford’s ponderous way with words frequently had me putting it down and sighing. Yes, I know it’s not fair to compare anyone’s writing with the work of one of the greatest English prose stylists, but in this case, how can you help it? Every now and then, Bradford quotes from one of Martin’s books. It’s like the sun sailing out from dense cloud.

In the end, I went back to Experience (2000), Martin’s own memoir (from which Bradford quotes intermittently), to try to make sense of my nagging feeling that there had to be a needle somewhere in this carefully piled-up hay. After the first few pages, I was hooked. Experience doesn’t bear any strict comparison with Bradford’s book, because it is not an autobiography. It chooses a few remembered events, in thematic rather than chronological order, tells them as vignettes, and reflects on them. Another caveat: it is subjective, selective, and crafted, as memoir must be, and no doubt Martin plays with the reader’s expectations as he plays with his former selves. And yet Experience has an ache of truth and beauty about it. It is moving and often very funny. We sense the middle-aged Martin’s acute embarrassment over his smart-arse schoolboy letters, his complex relationship with a father who was both beloved and infuriating. We gaze into his mouth in the mirror when he’s had all his top teeth removed, and we see extinction.

The difference with Experience is not just much better prose. Martin has a writer’s ego, of course, but in this book he allows himself no reverence. In Martin Amis: The Biography, Bradford is all reverence. Being placed on a pedestal is not a good fate for a writer, however brilliant.

Comments powered by CComment