- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Features

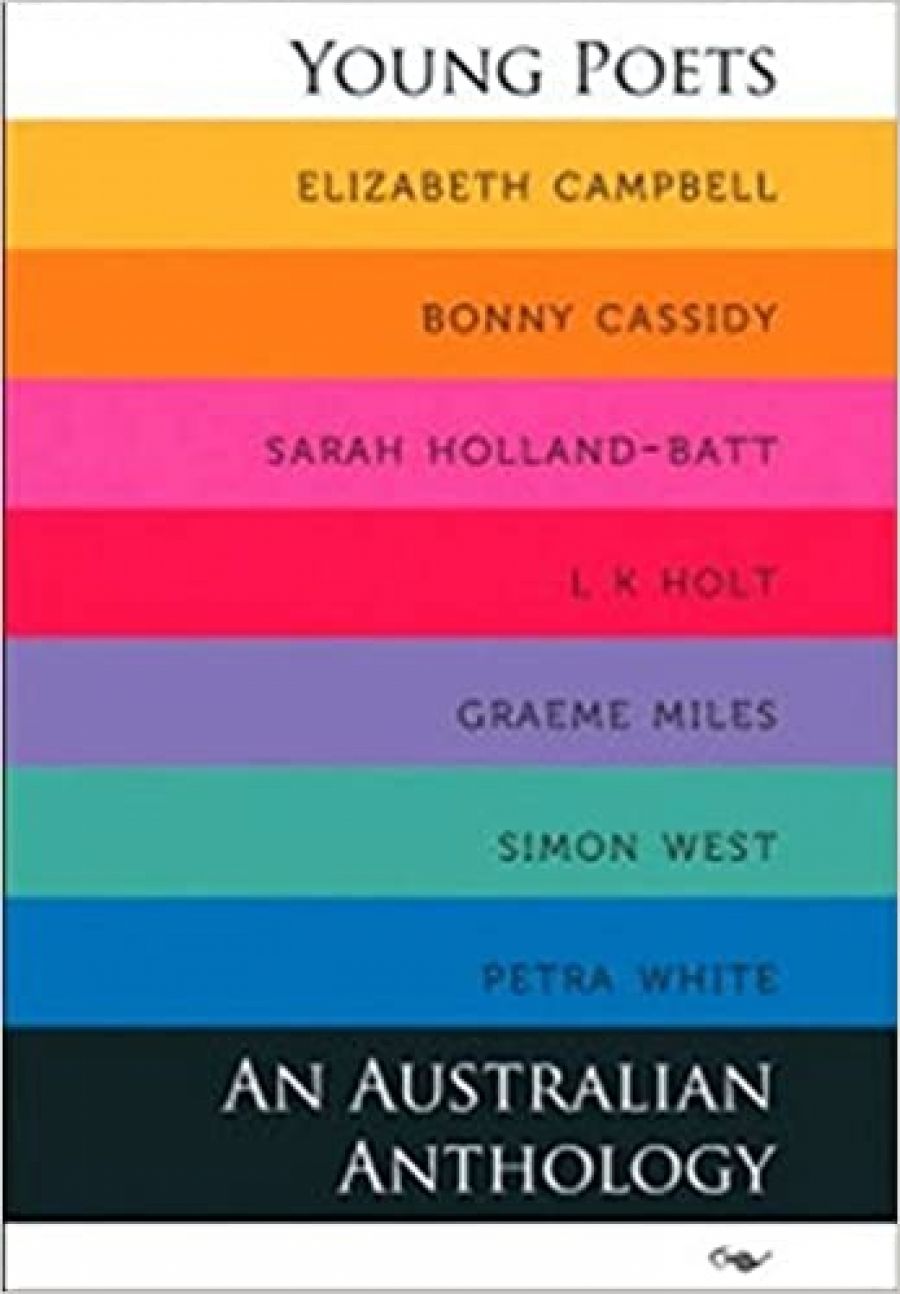

- Custom Article Title: Maria Takolander reviews 'Young Poets: An Australian anthology' edited by John Leonard

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

John Leonard’s anthology of young Australian poets, showcasing the work of an exclusive septet, comes hot on the heels of Felicity Plunkett’s more accommodating Thirty Australian Poets (reviewed by Fiona Wright in the December 2011–January 2012 issue of ABR). Young Poets: An Australian Anthology ...

- Book 1 Title: Young Poets

- Book 1 Subtitle: An Australian anthology

- Book 1 Biblio: John Leonard Press, $27.95 pb, 170 pp

Leonard’s claims to objectivity and authority are significantly compromised by his inclusion of three (out of seven) poets published by John Leonard Press (Petra White, L.K. Holt, and Elizabeth Campbell) and of two poets published by Puncher & Wattmann (Bonny Cassidy and Simon West) – the press that published Leonard’s previous anthology, The Puncher & Wattmann Anthology of Australian Poetry (2011). While UQP is represented by Sarah Holland-Batt, Fremantle Press by Graeme Miles, other publishers seem to have been relegated to the ranks of the eager and, by implication, easily fooled.

Leonard is explicit about his aesthetic. Poems that demonstrate a ‘true distinction in quality’ are not merely ‘prose chopped conveniently into lines […] a mere load-bearer for bright talk and polished-up images’, but poems that uphold the ‘lovely mode’ of free verse as ‘an audible dance’. They should be read aloud, he suggests, to the sea. Leonard has also chosen poets whose inclination is ‘to devour as much of poetry’s past and present traditions as possible, for the wide craft and spirit of the art’. The exclusion, then, of poets such as Lisa Gorton and Kate Middleton (Giramondo), Judith Bishop and Michael Brennan (Salt Publishing), Jaya Savige (UQP), Cameron Lowe (Whitmore Press) and Claire Potter (Five Islands Press), who are all under forty and at times practise a similar aesthetic – extraordinarily well – is hardly justified here.

And what about the depth and interest of poetry beyond that aesthetic? It is as if the Generation of ’68 – the starting point for the poets included in Plunkett’s welcoming and diverse anthology – never happened. While there is much meditation on birds and souls and a plethora of medieval or neoclassical references, there is little room in Leonard’s book for popular culture, comedy, or political outrage. Either we are dealing with a generation of young fogeys, or the selections are a little misleading. The anthology is also overwhelmingly white.

Putting aside the Preface, which can provoke the reader to challenge rather than embrace the selections, there is some fine poetry here. Beginning with Campbell and Holt – whose books I have reviewed in a previous issue of ABR (May 2008) – their work remains compelling and unsettling. Campbell ruminates on the soul in a sequence called ‘À Mon Seul Désir’, but her horse poems and the poem on seizures, titled ‘Brain’, are the ones that have stayed with me. Holt’s poems are finely worked as well as risk-taking. ‘Unfinished confession’ is, without a doubt, the bravest inclusion in the anthology. While this poem on transgender surgery contains a host of classical and literary allusions (including Galen, Aesop, Poe, and Proust), it also contains the refreshingly outrageous and comic: ‘The doctors eagerly awaited opening / night when the gonads would be unveiled, two luminaries / ready to burst like child-actors with their soliloquies.’

Holland-Batt’s poems are extraordinary for their assuredness and insight. Being an accomplished prose writer, she is unpretentious and skilled when it comes to handling line. Her selection includes a large quantity of bird poems, but these are striking for their imagery: a toucan, for instance, is pictured in ‘the dark tribunal of the trees’. Proving her range, there is also the polite satire of ‘Against Ingres’ and the electric imagery of ‘Medusa’: ‘I have always loved the translucent life, / the concentricities / blooming around me / in a wild ripple-ring of nerves.’

Miles, who has a PhD in ancient Greek literature, provides us with a number of poems on classical subjects, but also with some solitary poems on children and an isolated Surrealist poem, ‘Talking Glass’. West’s poetry, always measured, includes an ekphrastic poem on an Aboriginal painting – the only way in which indigeneity features in this anthology – and the strikingly vulnerable ‘After a self-portrait’, which ends: ‘The skin of my face is taut, just earth / at the end of summer. The wells on that plain / are very still, still and far down, as if they were afraid / and no one remained to draw up water.’

White’s poems incorporate references to Pompeii, Noah, Sisyphus, and Gilgamesh, although ‘Southbank’, a satirical and poignant portrait of the office worker, makes welcome references to the more contemporary and familiar. Cassidy goes further back in time, mining a ‘broad geology of the last sixty million years’ with a sequence called ‘Final theory’, which memorably describes an undersea camera as a ‘dream tunnel’ and contains the powerful lines: ‘All my words are gunning for extinction, all they can tell us is: / live more.’

Cassidy’s words are resonant, celebrating life and poetry as urgent multiplicity in a way that contrasts with the reification or fossilisation of poetry recommended by Leonard’s Preface. A vibrant and diverse culture of poetry exists in Australia – if only part of it is represented here.

Comments powered by CComment