There is at least one bravura performance in Melbourne right now, and it warranted a much larger house than we saw last week (February 1), when Southbank Theatre was only half full. The Royal Shakespeare Company’s production of William Shakespeare’s long poem The Rape of Lucrece was first seen in Australia during the recent Sydney Festival, but it was premièred almost two years ago, at the Swan Theatre in Stratford-upon-Avon.

On a sharp triangular stage – mostly gloomy, sometimes lit, with tall, distressed pictures hanging on the walls – Camille O’Sullivan recites and sings most of the 1855 lines (the performance lasts eighty minutes). Irishman Feargal Murray, her sympathetic accompanist on piano, helped to adapt the poem for the stage; Elizabeth Freestone is the director.

O’Sullivan – part French, part Irish, a former architect and painter who now devotes much of her career to music – bounds onto the stage in a dark fascist overcoat and introduces the poem (rarely performed, rarely listed as one of Shakespeare’s major works) so urgently and accessibly that it takes a moment before we recognise the verse. Lucrece (1594) and the earlier Venus and Adonis (1593) were conceived as a pair (both are dedicated to Henry Wriothesley, Earl of Southampton). The Lucrece stanza has an additional rhyme (ababbcc): Venus and Adonis is ababcc.

The scene itself, unlike that of the al fresco Venus and Adonis, is claustrophobic: a tent in ‘the besieged Ardea’ of the opening line. Brilliantly, with her excellent vocal resources, O’Sullivan introduces her three characters: the cavalier Collatine, who boasts of his wife’s beauty and virtue, and rashly leaves her alone; the visiting Tarquin, who listens and resolves to have her; and Lucrece herself, ‘Lucrece the chaste’, a phrase which tells us everything until after the rape, when notions of honour and shame rouse her.

Camille O'Sullivan as Lucrece (photograph by Keith Pattison)

Camille O'Sullivan as Lucrece (photograph by Keith Pattison)

Tarquin’s lengthy approach to the tent is most suspenseful (the lighting is deft), and the rape itself generates colossal tension; rarely is an audience so attentive, so respectful. O’Sullivan – throwing off Tarquin’s brute coat and becoming the supine victim in her slip – conveys Lucrece’s terror and outrage. When she sings the verses, as she often does, O’Sullivan’s vast cabaret experience is evident; the voice is strong but flexible, and highly emotive.

Rape done, Tarquin (‘this faultful lord of Rome’), sickly sated, makes his exit:

He like a thievish dog creeps sadly thence;

She like a wearied lamb lies panting there;

He scowls and hates himself for his offence;

She, desperate, with her nails her flesh doth tear;

He faintly flies, sweating with guilty fear;

She stays, exclaiming on the direful night;

He runs and chides his vanished, loathed delight.

Lucrece – left a ‘hopeless castaway’ – summons Collatine, intent on revenge, only to stab herself on his arrival, a cue to two of the most vivid stanzas in the poem:

Stone-still, astonished with this deadly deed,

Stood Collatine and all his lordly crew;

Till Lucrece’s father that beholds her bleed,

Himself on her self-slaughtered body threw;

And from the purple fountain Brutus drew

The murderous knife and as it left the place,

Her blood, in pure revenge, held it in chase;

And bubbling from her breast, it doth divide

In two slow rivers, that the crimson blood

Circles her body in on every side,

Who like a late-sacked island vastly stood

Bare and unpeopled, in this fearful flood.

Some of her blood still pure and red remained,

And some looked black and that false Tarquin stained.

O’Sullivan – weary after this virtuoso reading and performance – is clearly moved at the end, as is the audience. No one interested in innovative theatre or Shakespeare’s poetry should miss this unforgettable performance.

The Royal Shakespeare Company production of The Rape of the Lucrece is presented at the Sumner Theatre, Melbourne Theatre Company, 6–10 February 2013.

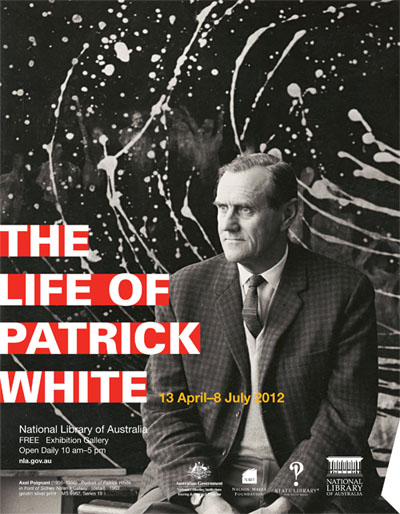

While the magazine (due tomorrow) is being printed, the May issue is now available to Australian Book Review Online Edition subscribers. After spending the past few days uploading this month’s ABR (with highlights including David Marr on Patrick White in Adelaide, and a review of Susan Swingler’s sensational family memoir on the Jolleys), I will be grateful to swap the pixels for ink and get back to some good old head-down reading. But I encourage all ABR readers to explore the Online Edition. Print subscribers can add-on a year’s subscription for just $20. An online-only subscription costs $40.

While the magazine (due tomorrow) is being printed, the May issue is now available to Australian Book Review Online Edition subscribers. After spending the past few days uploading this month’s ABR (with highlights including David Marr on Patrick White in Adelaide, and a review of Susan Swingler’s sensational family memoir on the Jolleys), I will be grateful to swap the pixels for ink and get back to some good old head-down reading. But I encourage all ABR readers to explore the Online Edition. Print subscribers can add-on a year’s subscription for just $20. An online-only subscription costs $40. To Canberra on 12 April for the opening of a new travelling exhibition, The Life of Patrick White.

To Canberra on 12 April for the opening of a new travelling exhibition, The Life of Patrick White. Although private patronage and the arts have been linked for centuries, cultural philanthropy has not typically been associated with literature in the same way that it is with art galleries, libraries, museums, and performing arts companies. But this is changing. Since we launched our

Although private patronage and the arts have been linked for centuries, cultural philanthropy has not typically been associated with literature in the same way that it is with art galleries, libraries, museums, and performing arts companies. But this is changing. Since we launched our  We always enjoy meeting our Patrons, and throughout the year we host of range of events, with noted speakers such as Alex Miller and Patrick McCaughey.

We always enjoy meeting our Patrons, and throughout the year we host of range of events, with noted speakers such as Alex Miller and Patrick McCaughey. Hot off the press – possibly the longest of recorded literary longlists, for this year’s Miles Franklin Literary Award, which is worth $50,000 – not quite prime ministerial, but still premiership material, and well worth winning, apart from the kudos attached to Australia’s pre-eminent literary competition.

Hot off the press – possibly the longest of recorded literary longlists, for this year’s Miles Franklin Literary Award, which is worth $50,000 – not quite prime ministerial, but still premiership material, and well worth winning, apart from the kudos attached to Australia’s pre-eminent literary competition. In his Seymour Biography Lecture ‘Pushing against the Dark: Writing about the Hidden Self’, repeated at Adelaide Writers’ Week and soon to be published in ABR’s April issue, Robert Dessaix (struggling to appreciate the new genre) likens the intimacy of blog-writing to that of striptease.

In his Seymour Biography Lecture ‘Pushing against the Dark: Writing about the Hidden Self’, repeated at Adelaide Writers’ Week and soon to be published in ABR’s April issue, Robert Dessaix (struggling to appreciate the new genre) likens the intimacy of blog-writing to that of striptease. To Adelaide for the last day of Writers’ Week, now an annual affair (ambitiously, some think) under the guidance of Laura Kroetsch (Director). Ms Kroetsch, an American, joins Adelaide from Wellington, where she ran the literary festival for many years. The removal of long-time director Rose Wight created some heat in certain quarters, but I didn’t share the forebodings about what Ms Kroetsch might do to Writers’ Week, now more than fifty years old, and still based in the Pioneer Women’s Memorial Garden. Change was clearly overdue.

To Adelaide for the last day of Writers’ Week, now an annual affair (ambitiously, some think) under the guidance of Laura Kroetsch (Director). Ms Kroetsch, an American, joins Adelaide from Wellington, where she ran the literary festival for many years. The removal of long-time director Rose Wight created some heat in certain quarters, but I didn’t share the forebodings about what Ms Kroetsch might do to Writers’ Week, now more than fifty years old, and still based in the Pioneer Women’s Memorial Garden. Change was clearly overdue.