- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Literary Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The burdens and genius of Charles Dickens

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

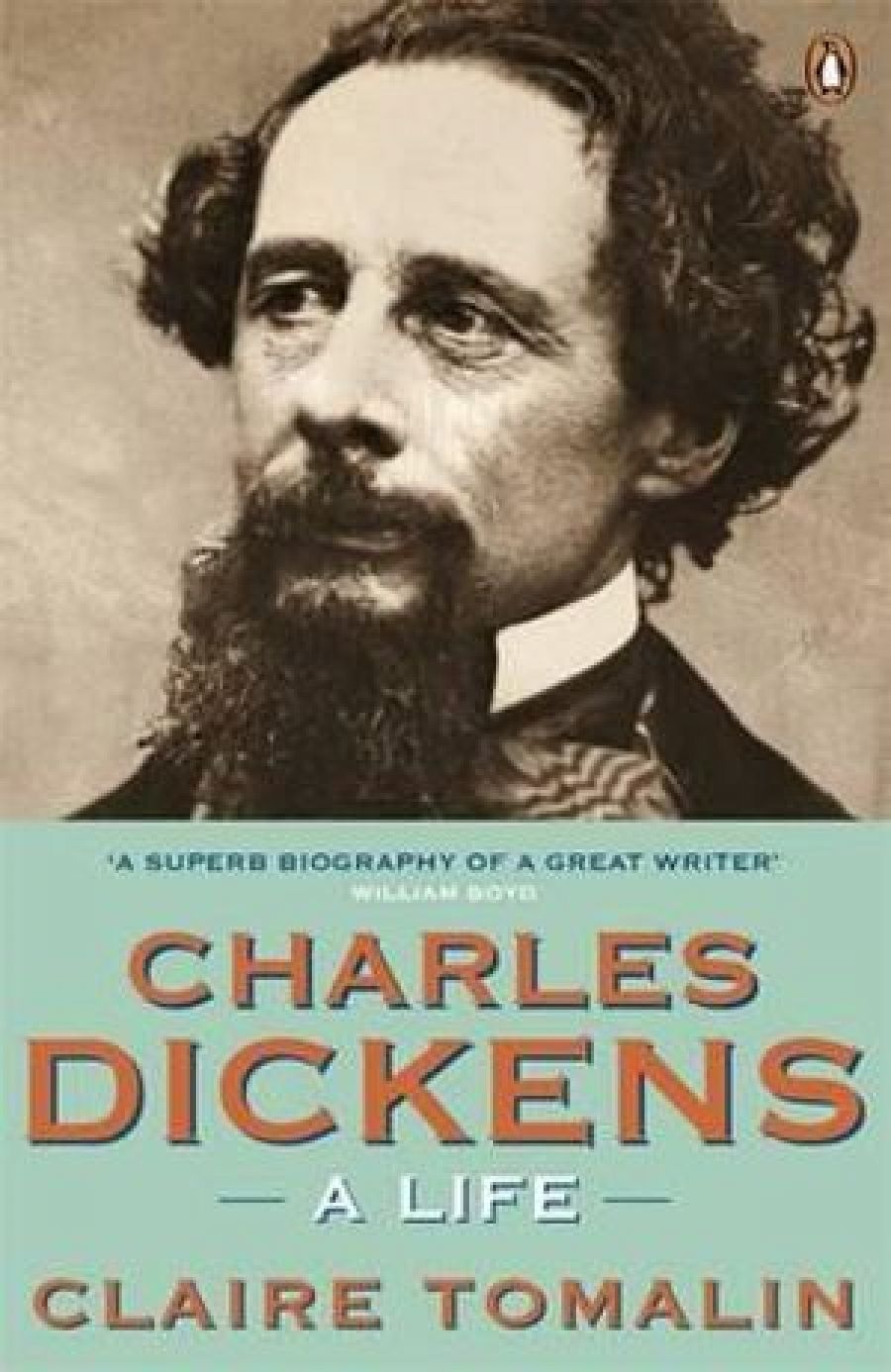

This is how Claire Tomalin closes her Dickens biography: ‘He left a trail like a meteor, and everyone finds their own version of Charles Dickens’, followed by a long list of types. I consider Dickens the surrealist, or the sentimentalist, but then I pick Dickens the tireless walker. And I concede, with Tomalin, that regarding his life and work, ‘a great many questions hang in the air, unanswered and mostly unanswerable’.

- Book 1 Title: Charles Dickens

- Book 1 Subtitle: A life

- Book 1 Biblio: Viking, $39.95 hb, 574 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.booktopia.com.au/charles-dickens-claire-tomalin/book/9780141036939.html

- Book 2 Title: Becoming Dickens

- Book 2 Subtitle: The invention of a novelist

- Book 2 Biblio: Harvard University Press, $39.95 hb, 389 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Cover Path (no longer required): images/ABR_Digitising_2021/Archives_and_Online_Exclusives/becoming-dickens.jpg

All his life Dickens walked: when he lost his first love and when he wooed his last; when his children were born; when relatives or friends died; when he was escaping domesticity, or developing an idea. This habit of walking matches the Dickens we know best: the creator of unforgettable characters and evoker of an England which is so closely observed, so finely depicted, that it still echoes in our present-day sense of place, especially in London. His walking, like his character Little Nell’s favourite ‘wanderings in the evening time’, also give hints of someone who was both sociable and solitary.

Tomalin’s biography opens with Charles Dickens ‘born on Friday, 7 February 1812, just outside the old town of Portsmouth in the new suburb of Landport, built in the 1790s’. Tucked into this sentence is Tomalin’s central point: of Dickens poised between old and new, between alternatives. Her conjectural agility is a good match for her subject’s ambiguities, as she assesses, for example, Charles’s father, John Dickens, a man who gave himself airs. He ‘may have been the son of the elderly butler [at Crewe Hall], but it is also possible that he had a different father – perhaps John Crewe, exercising his droit de seigneur ... or another of the gentlemen who were regular guests ... Or he may have believed that he was.’

Dickens’s most famous character, Micawber, was based on his father, and in describing this trinity of father, son, and literary creation, Tomalin points to the expansiveness – the exuberance, the melodrama, the elaboration – that we now regard as quintessentially Dickensian. ‘John Dickens was expansive by nature, with a tendency to speak in loose, grand terms, and an easy way with money.’ We learn that, like his father, Charles was also inclined to exceed, he wrote too much, smoked and drank too much, gave away money, and, by his own admission, had too many children. He was English to the core, but fell in love with Paris and wished he was French. Tomalin suggests that Dickens stretched himself physically, socially, and emotionally. One example of his striving and restlessness occurred in the mid-1850s, when he experienced the writing of Little Dorrit (1855–57) as a painful, physical force ‘breaking out all round me’, so that he was compelled to walk all day and prowl about into ‘the strangest places in London by night’. His friend the painter Edwin Landseer said, ‘I should like to catch him asleep and quiet now and then.’ No such luck: according to Tomalin, ‘he did not pause until the day he fell unconscious to the ground’.

Tomalin tells us all the iconic stories, which feature in other Dickens biographies: how as a child of nine, when the family lived in Kent and ‘Dickens became fully aware of the world around him and began to store up impressions’, he admired a mansion and his father told him if he worked hard he would one day own a big house just like that. The house he coveted was Gads Hill Place, which he bought in 1856. Kent became the setting for what is arguably his highest achievement, Great Expectations, published in 1860–61. Tomalin suggests that Great Expectations is not a realistic account, but came ‘out of a deep place in Dickens’s imagination which he never chose to explain’. She calls it ‘an almost perfect novel’.

We are told how the Dickens family moved around a great deal, his father was sent to Marshalsea debtors’ prison, young Charles’s education was neglected and he was obliged to work in a shoe blacking factory, and how, from an early age, in his own words, his whole nature ‘was penetrated with grief and humiliation’. He dealt with this by walking and later also by writing, taking care to ‘keep hold of every part of his life, and relate each to the others’. Most of his biographers agree that he was catching up on boyhood all his life.

By 1840, aged twenty-eight, ‘Dickens knew himself to be famous, successful and tired’. His marriage to Catherine Hogarth in 1836 he would later consider to have been his worst mistake, despite her devotion to him and the ten children they had together. Instead, he loved his sisters-in-law, Mary, who died young and whose ring he wore, and Georgina, who became his housekeeper and confidante, as well as the young actress Ellen (Nelly) Ternan. And of course he loved John Forster, his best friend and chosen biographer.

When Dickens experienced financial problems in the 1840s, he hoped a trip to America would benefit his career. But after an optimistic start he was disenchanted, and ‘going into slave-owning states so upset him for its blatant inhumanity that he decided to turn back after a short stay in Richmond, Virginia’. He packed his ever-growing family into large coaches to travel with him in Italy, Switzerland, and France. He thought Paris was ‘the most extraordinary place in the World ... almost every house, and every person I passed, seemed to be another leaf in the enormous book that stands wide open there’.

Tomalin believes that in his fight against social injustice, and by visiting hospitals, asylums, and jails to report on their conditions, Dickens was like Carlyle and Engels, ‘all fired with anger and horror at the indifference of the rich to the fate of the poor’. He gave financial assistance to his parents and to many friends. In 1847 he established a Home for Homeless Women and helped several of them migrate to Australia. He was especially kind to orphans; it might be said they were his specialty. Abandoned, damaged, unhappy children dominate the conscience of his narratives, and his own favourite book was David Copperfield (1849–50). Tellingly, towards the end of his life Dickens referred to his work as his child.

Forster warned critics and future biographers that ‘it will not do to draw round any part of such a man too hard a line’. But Tomalin has her own views on Dickens and teases out some previously hidden contours. Her greatest worry is his relationship with, and portrayal of, women. She suggests that he ‘did not want a wife who would compel his imagination’ and married a ‘blank and blushing innocent’ for sexual hygiene, domestic comfort, companionship – only to get a shock during their honeymoon in Kent, when he discovered that Catherine was not a walker. After that it was the ‘writing desk and walking boots for him, sofa and domesticity for her’. She was perpetually pregnant. Then, claiming that ‘poor Catherine and I are not made for each other’, he left her and took up with Nelly Ternan.

According to his daughter Katey, his breaking up of the household and abandonment of Catherine caused great misery. Angry at the moral implications of his actions, and the critical attitude of friends, including Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Mrs Gaskell, and Thackeray, he ‘behaved like a madman’. Tomalin believes that he had a son with Nelly and that the child died. She also argues that his preference for insipid women meant that he was unable to create complex female characters.

Aged fifty-eight, Dickens finally exhausted himself. The meteor – flashy dresser, father of ten, esteemed author, lover of games and raspberries, the man who wasn’t satisfied to reach the top of Vesuvius, but had to crawl to the crater’s edge to look into the fire – burned out in 1870. His books carry the light.

Keeping control of every part of his life meant that Dickens was not just ‘an obsessive organizer of his surroundings, even rearranging the furniture in hotel rooms’, but, as Tomalin points out, ‘his pursuit of various goals was so energetic, and he demonstrated such an ability to do many different things at once, and fast, that even his search for a career had an aspect of genius’. This preoccupation with self-invention is examined more thoroughly by Robert Douglas-Fairhurst in Becoming Dickens: The Invention of a Novelist.

Before he was a novelist, Dickens flirted with careers as an actor, stage manager, journalist, and clerk. He also thought about emigrating. And having imagined these alternatives, he later created characters who chose those paths, ‘so his fiction teems with surrogate selves ... fragments of disguised autobiography’. Douglas-Fairhurst argues that biography is not just about hard facts, but must include the what if factor, which looks into the alternatives everyone faces at life’s crucial moments. So we might well ask, what if – like two of his sons and some of his characters – Dickens had come to Australia?

Douglas-Fairhurst writes, ‘the story of what did happen can never fully erase the ghostly outlines of history’s rejected drafts’. His ‘counterfactual investigation’ makes a fascinating case for Dickens the experimenter, someone who set out with every new book to discover the potential of his craft, and who filled his work with scenes of speculation, so that it offers ‘many possible narrative outcomes’. I agree. Charles Dickens’s best work considers every smallest aspect and larger connotation, tentatively, thoughtfully, suspensefully. Therein lies its magic.

Comments powered by CComment