- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Society

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Australia’s penchant for panic

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

David Marr is not on the list of Australian living treasures, but perhaps he should be. Among our best journalists, he stands out as someone who has consistently challenged the powerful, at his best with forensic skill and deep research. Like other journalist–authors such as Anne Summers and George Megalogenis ...

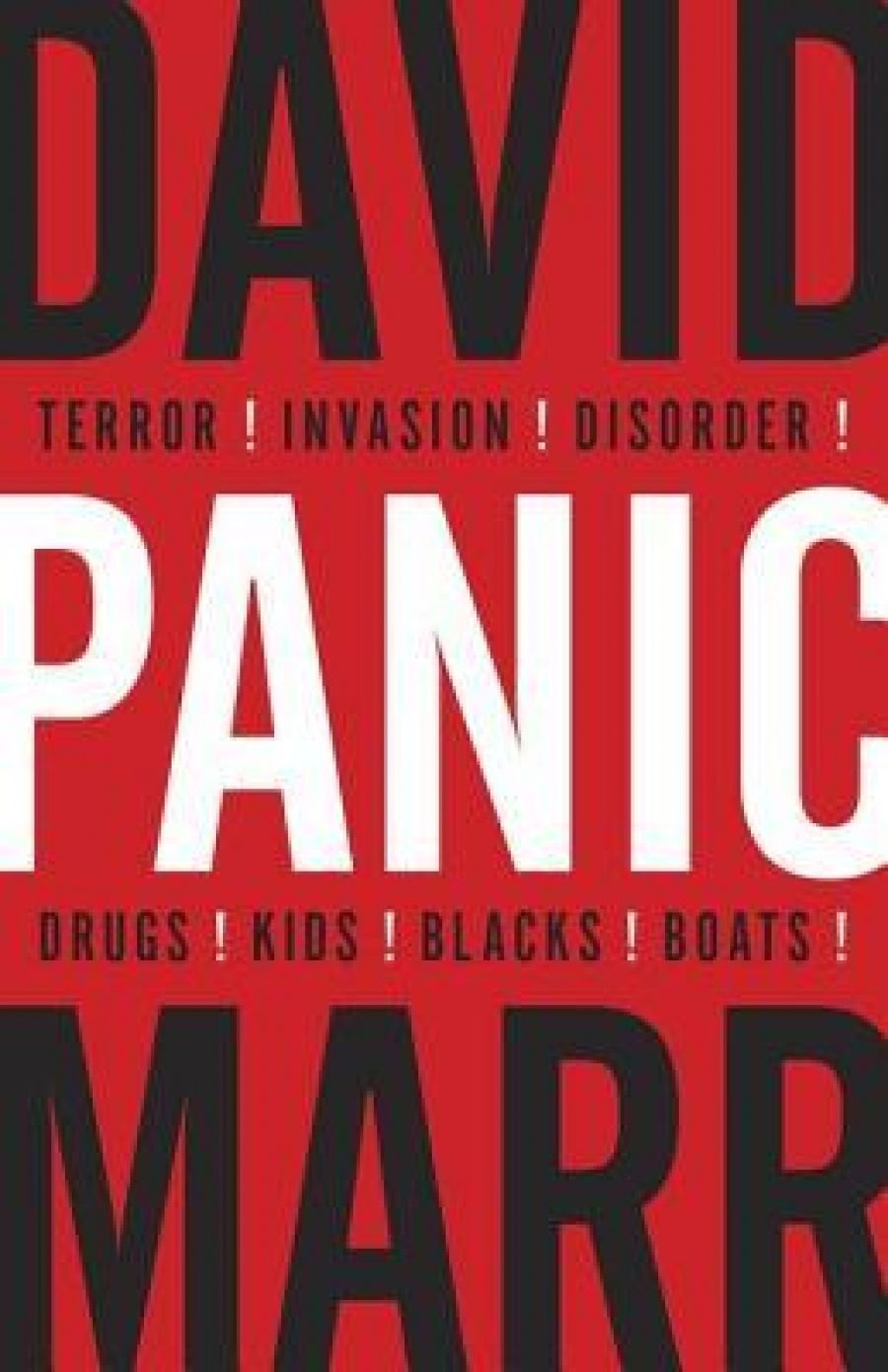

- Book 1 Title: Panic

- Book 1 Subtitle: David Marr

In case this sounds ingratiating, let me note that I have known David Marr for thirty years, though never well; we have never had a meal together. In the exuberance of the early gay movement, I felt that Marr was too slow to join in, while he probably suspected me of being overly zealous. (Not surprisingly, I found his one essay in Panic on the gay movement somewhat pedestrian.) But I agree with Marr that homosexuality is no longer in itself the basis for panic within Australia.

Marr may well be Australia’s leading moralist. I use the term not in the sense one might apply to Cardinal Pell or Alan Jones, both of whom conflate morality with defence of the status quo, but in the more radical sense of someone who demands of us a greater level of humanity and holds us to account for our national hypocrisy.

Marr’s career – whether at the National Times, Four Corners, Media Watch, or the Sydney Morning Herald – is one of the most significant in contemporary journalism. Out of it came several important books, especially Dark Victory (2003),in which he and Marian Wilkinson laid bare the lies and manipulation of John Howard’s asylum seeker policies. He also wrote a major biography of Patrick White (1991), perhaps the most significant literary biography in Australian culture.

But even the best writers do not necessarily benefit from the quick bundling of old essays into new books. Panic strives to be more than a collection of ‘the best of’, and Marr has written a new introduction and conclusion in which he sets out a framework that explains the choice of essays. Put starkly, the thesis is that far from being a relaxed and comfortable society, ours is one permanently haunted by fear, above all fear ‘of being overrun by dusky fleets sailing down from the north’. Certainly, this is a motif in Australian history, and one that historians have consistently discussed. Marr adds details, but his conceptual framework remains fairly simplistic, and is largely aimed at the Liberal Party under Howard and now Tony Abbott:

For those shock jocks and newspaper columnists, the Labor Party and shadowy forces out on the Left are to blame for all the catastrophes closing in on Australia. There is an adage about the tabloids I once put to Bob Carr: that their purpose is to persuade the working class to vote Tory. He replied: ‘I think it is incontrovertible.’

‘Duh’, as my nephew might reply: had Carr disagreed, thatwould be worth recording.

To illuminate his thesis Marr has somewhat reworked a number of former journalistic pieces, mainly on racial politics (Pauline Hanson, Wik, asylum seekers, the Cronulla riots, etc.), with a couple of pieces aimed to show panic over other issues, such as fear of terrorism, child sexuality, and drugs. For this book, Marr has written a new and heartfelt chapter on the insanity of the current hysteria over illicit drugs, which one hopes was put in the Christmas stockings of a number of our MPs. But the heart of the book is his justifiable anger and dismay at the demonisation of asylum seekers, and his sense that our political leaders have betrayed us. I suspect most readers of Panic will share Marr’s indignation, but I fear the book will not change the minds of anyone who disagrees.

There is a nice rhetorical flourish to the claim that ‘I’ve come to believe the fundamental contest in Australian politics is not so much between Right and Left as panic and calm’, but to substantiate such a claim requires more than examples of panic-mongering. There are few societies whose politicians are not skilled at manipulating irrational fears, and there is an extensive literature, which Marr ignores, on the creation and management of moral panics.

Moreover, there are a number of counter-cases where moral panics have been hosed down by political leaders and Australians have responded in rather different ways. The dismantling of the White Australia Policy was largely successful with remarkably little of the sort of hostile fearmongering that Pauline Hanson represented, in part due to conservative politicians such as Abbott. And while the emergence of Aids induced considerable media panic, the responses of the federal and most state governments were among the sanest in the Western world.

The problem with Panic is that it is written entirely from within Australia, and so avoids the obvious question as to whether we are more prone to moral panics than other peoples. Marr states that ‘Panic is so Australian.’ Well, yes: but it is also Malaysian, American, and even Danish. David Marr’s moral indignation is admirable, but it should be tempered with a more analytic dispassion.

Comments powered by CComment