- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: ‘O Rare Ben Jonson’

- Article Subtitle: A definitive biography of Shakespeare's great rival

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Ambitious, arrogant, talented, brave, learned, truculent, and convivial: Ben Jonson was too outstanding, too odd, and too contrary to be taken as a creature of his time. Yet he had so wide-ranging a life that to write his biography is to capture, in little, a great part of his remarkable age.

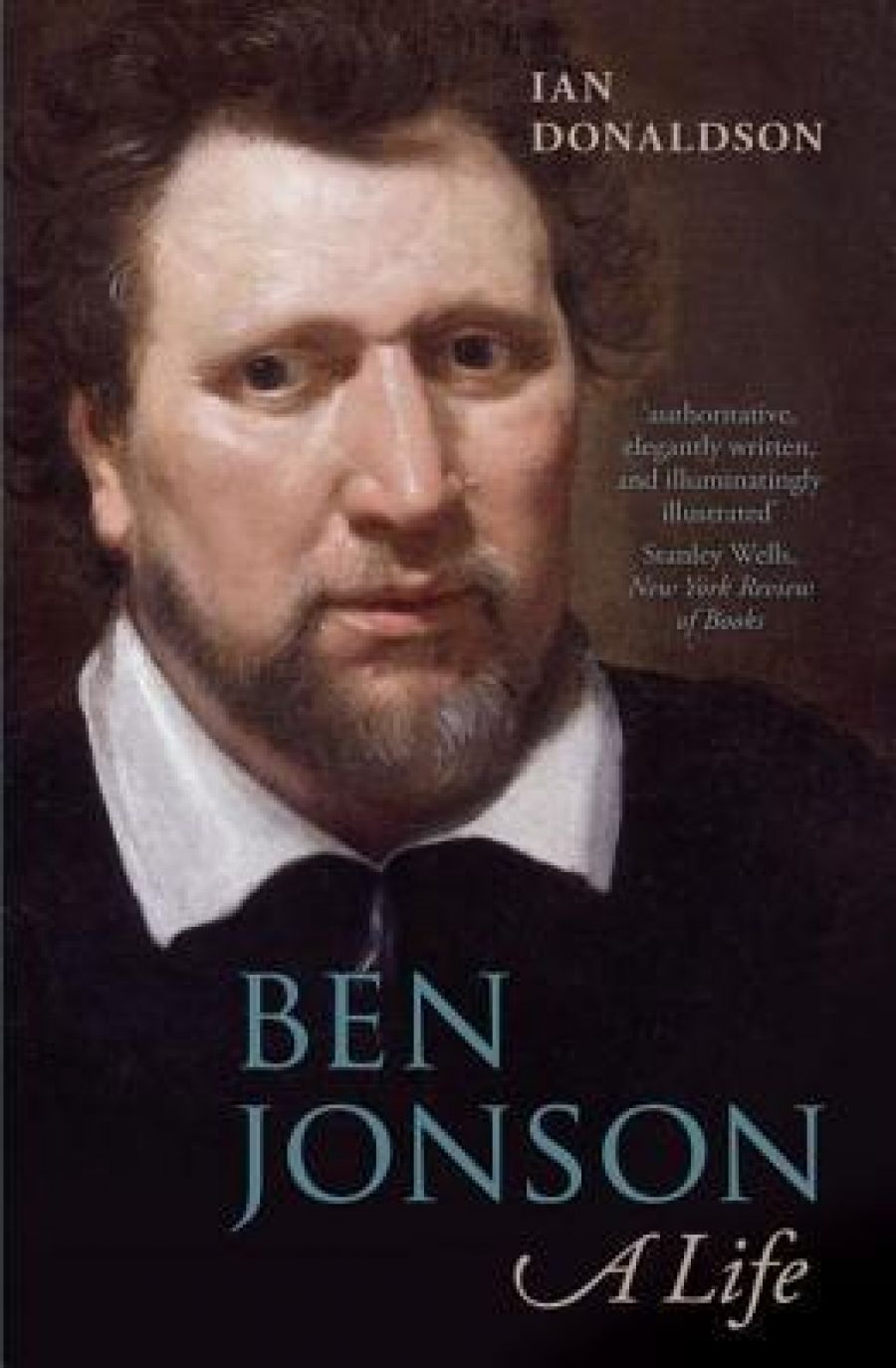

- Book 1 Title: Ben Jonson

- Book 1 Subtitle: A Life

- Book 1 Biblio: Oxford University Press, $48.95 hb, 552 pp, 9780198129769

Jonson was born in London in 1572: eight years after Shakespeare, in the same year as John Donne, and sixteen years before Thomas Hobbes. He was friends with them all. In his lifetime, London became a metropolis. He saw the rise of the shopping mall, the coffee house, the idea of credit, and the trade of luxury goods. He lived through the colonisation of the new world, the development of telescopes, and the new philosophy of space. He was part of that flourishing of English literature, when Greek and Latin works were ‘Englisht’, and when English writers made a national literature of their own.

It was also an age of plague, unrest, religious war, martyrdom, torture, and espionage. These, equally, shaped Jonson’s experience. He served with the army in the Low Countries. His son died of the plague. He was arrested, imprisoned, and tortured after his co-written play The Isle of Dogs was reported to be ‘very seditious and slanderous’. Many years later, Jonson reported that ‘his judges could get nothing of him to all their demands but “ay” and “no”’ – an impressive claim: his interrogators included the notorious torturer, Richard Topcliffe.

Jonson’s age seems in some ways close to ours; in others, startlingly remote. So many of the theories, the literary forms, the metaphors, and the words that we use now were born then. It is hard to avoid that trick of retrospect which overlooks the accidents of history and sees all that has endured as modern, as against all that has passed away. All the same, Jonson’s life seems remarkable in its variousness. The stepson of a bricklayer, he became the king’s poet. A court writer, he ate dinner with the Gunpowder plotters. An Anglican, he converted to Catholicism for a time. Twice a duellist, branded on his hand for killing a man, he was in his writing fastidious and compelled by the idea of decorum. He wrote in different forms, and for disparate audiences: epigrams and verse epistles for friends, poems for noble patrons, entertainments for London companies, translations for the new reading public, masques for the court, and satirical comedies for the public stage. He was one of the first writers to collect and publish the full range of his work. Though fierce in rivalry and jealous of acclaim, he wrote a remarkably generous tribute to Shakespeare.

These days, universities are meant to work like businesses, and academics are meant to publish, every year, a quantity of articles. Ours is the age of the academic thesis and the academic article. When you consider a period as various and fast-changing as early-modern England, such forms – typically tendentious and unaccommodating – often give a misleadingly narrow point of view. I have sat at dinner, for instance, with a writer who thought that Donne should have chosen martyrdom over Anglicanism, as though there were no ground between the two and no honour left for those who would rather live. In such a context, Donaldson’s biography of Jonson is a rare and valuable achievement. Elegant in style, flexible in approach, and characterised by a tone of intelligent curiosity, it is engaging as well as definitive. It allows for the complexity of that time when a Catholic with a brand on his hand could write for a king.

For the most part, Donaldson takes Jonson’s life phase by phase, and gives each phase its defining characteristic. This allows him to trace, chapter by chapter, the various ways in which Jonson’s work took up the life of his time. Donaldson shows, for instance, how the founding of a new shopping mall sparked Jonson’s satiric wit in Bartholomew Fair, and how the discovery that one of his patrons was impotent prompted him to cut short one of his poems in print, marked by a tag, ‘the rest is lost’. Donaldson has a gift for selecting the telling detail: for instance, how the word ‘plot’ took on new meaning after the discovery of the ‘Gunpowder Plot’. In this way, Donaldson marshals his extraordinary knowledge into a story full of glimpses of daily life.

The biography concentrates on how Jonson’s work reflects the social and political life of his time. Donaldson spends less time on how Jonson’s poems relate to the work of his contemporaries. Along with David Bevington and Martin Butler, Donaldson has spent more than ten years editing The Cambridge Edition of the Works of Ben Jonson; this biography should serve as an unofficial companion to that imminent edition and its close textual analysis, for if Jonson was in many ways an outward-looking writer, curious and satirical, he was nevertheless immersed in writing, new and antique. He often borrowed and condensed images and phrases. Donne’s lines, in particular, echo through Jonson’s work. This is, perhaps, what Jonson meant when he claimed that he was ‘better versed and knew more in Greek and Latin than all the poets in England and quintessenced their brains’ – a claim dryly noted by his host in Scotland, William Drummond of Hawthornden, who seems to have found him a trying guest. Jonson was also a careful and deliberate writer who ‘vext’ his lines. Not for him the sprezzatura, real or assumed, of the courtier-poet. His model of a learned, judicious, and analytical writer was a defining part of his legacy.

The book opens and closes with a sense of Jonson’s life in history. Donaldson shares Jonson’s fascination with how reputations rise and fall. Jonson defended poetry as the arbiter of history: the rise and fall and rise of his own reputation itself suggests the precariousness of fame. In the biography’s closing chapter, Donaldson traces how Jonson’s reputation fell with the rise of the Romantics, who took Shakespeare as their guiding light. In a prologue full of marvels, Donaldson tells the story of Jonson’s bones. Jonson once asked Charles I to grant him eighteen square inches of ground. The King agreed and asked him where that ground might be. ‘In Westminster Abbey,’ answered Jonson. He is buried there under the simple epitaph, ‘O Rare Ben Jonson’. Donaldson describes how Jonson’s grave was opened three times in the nineteenth century; and how – in a twist that would have delighted Marston – Jonson was buried not only upright, but upside down. Think of Hamlet handling Yorick’s skull, or of Donne’s poem ‘The Relique’: ‘When my grave is broke up againe / some second guest to entertaine ...’ There fall often these moments in sixteenth-century studies when images, whose meaning is for us almost entirely emblematic, turn out to have had their life in fact. So many people tried to filch Jonson’s skull that its resting place now is lost.

If this account brings home the anonymity of bones, there survives nonetheless plenty of material to flesh out Jonson’s life and character. ‘A staring Leviathan’ with ‘a parboiled face ... punched full of oilet holes, like the cover of a warming pan’ was how Thomas Dekker described him. Late in life, Jonson described himself as:

a tardy, cold,

Uncomfortable chattel, fat and

old,

Laden with belly, and doth hardly

approach

His friends, but to break chairs or

crack a coach.

His weight is twenty stone within two

pound,

And that’s made up as doth the

purse abound

(‘Epistle on My Lady Covell’)

When it came to burying Jonson, eighteen square inches might not have sufficed.

Donaldson’s biography wonderfully evokes Jonson’s friendship with poets and writers, ‘the tribe of Ben’. ‘Howsoe’er, my man / Shall read a piece of Vergil, Tacitus, / Livy, or of some better book to us, / Of which we’ll speak our minds, amidst our meat ...’: if Jonson’s celebrated lines inviting a friend to supper give the flavour of their enjoyment, so too do some remarks his neighbour and friend, James Howell, made in a letter:

I was invited yesternight to a solemn supper by B.J., where you were deeply remembered. There was good company, excellent cheer, choice wines, and jovial welcome. One thing intervened which almost spoiled the relish of the rest, that B. began to engross all the discourse, to vapor extremely of himself, and vilifying others to magnify his own Muse. T. Ca. [Thomas Carew] buzzed me in the ear that, though Ben had barrelled up a great deal of knowledge, yet it seems he had not read the Ethics, which, among other precepts of morality, forbid self-commendation ...

Ben was obviously a character both teased and beloved. In one sad and celebrated adventure, he travelled to Europe as tutor to Sir Walter Ralegh’s son, Wat Ralegh, who got him drunk and wheeled him around the streets in a barrow.

But probably Ben Jonson’s most famous adventure was his journey on foot from London to Edinburgh in 1618. Donaldson’s biography includes details from a manuscript which the Edinburgh scholar James Loxley recently discovered among some Aldersey family papers: ‘My Gossip Joh[n]son his foot voyage and mine into Scotland.’ For all their dryness, these notes offer a rich picture of the journey: how they were pursued by ‘a lunatic woman’, who went dancing in front of them, as well as ‘a humourous tinker’ and some minstrels with a song about the Earl of Essex; how Jonson bought new shoes at Darlington, and how in Sherburn they ate ‘cherries in the midst of August’.

Comments powered by CComment