- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

When the book arrived for review, a paperback of 656 pages, my heart sank. Americans are the world’s greatest researchers. Reading it would be like drinking from a fire hose. But it began incisively, with a turning point in the 2008 presidential campaign that established Obama’s audacity as a ‘complex, cautious, intelligent, shrewd, young African-American man’ who would project his ambitions and hopes as the aspirations of the United States of America itself. Soon we were in Kenya, with Tom Mboya, Jomo Kenyatta, the Mau Mau uprising, and Barack Hussein Obama Sr, a promising young economist with a rich, musical voice and a confident manner on his way to the University of Hawaii. We also meet the most compelling character in the book, perhaps in Obama’s life: his mother, a seventeen-year-old from Kansas, intrepid and idealistic, who takes up with the dasher from Kenya, becomes pregnant and marries him.

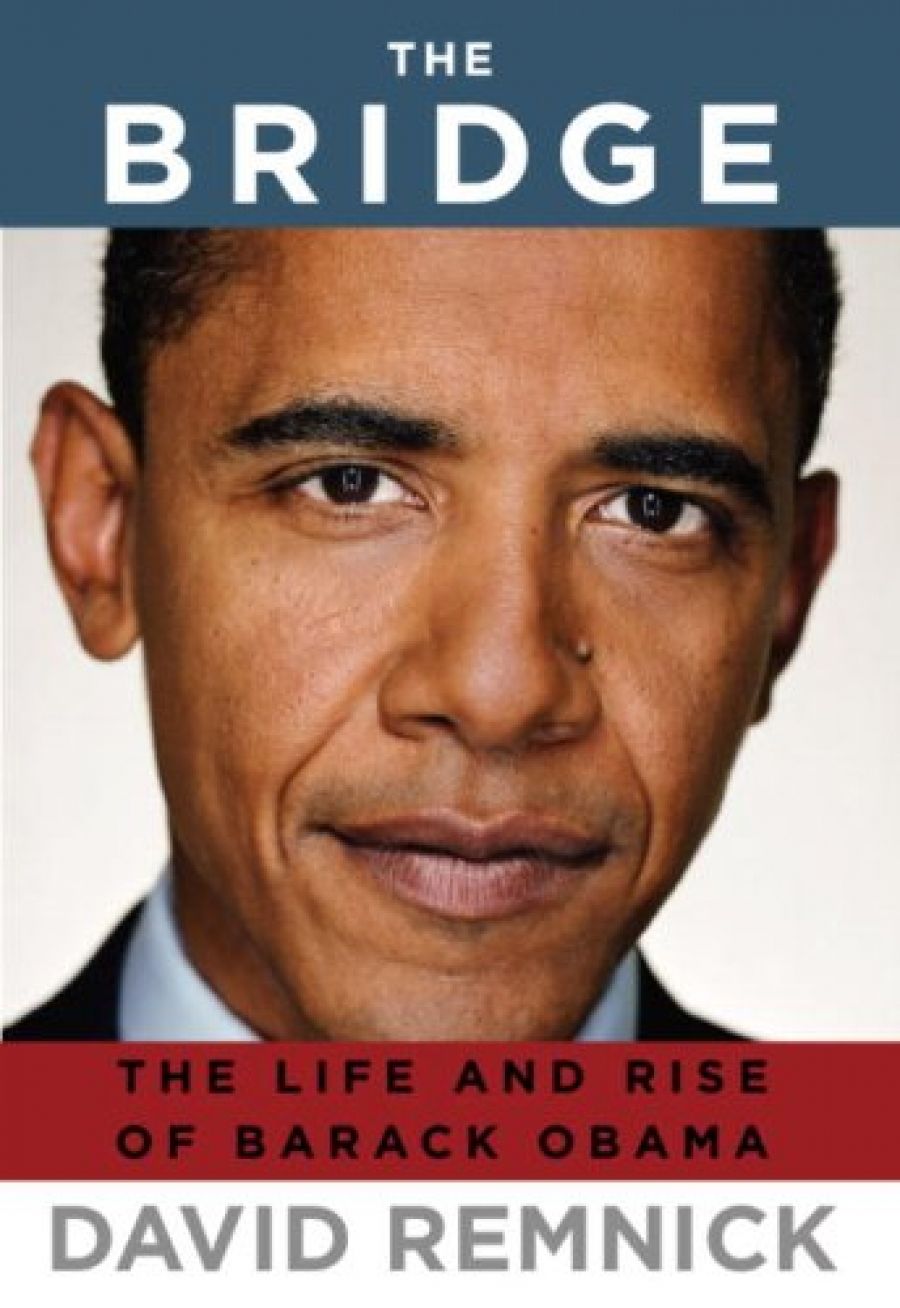

- Book 1 Title: The Bridge

- Book 1 Subtitle: The life and rise of Barack Obama

- Book 1 Biblio: Picador, $39.99 pb, 656 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://booktopia.kh4ffx.net/x7LKv

Stanley Ann Dunham (‘Hi, I’m Stanley, my father wanted a boy’) was born in 1942 while her father was on wartime service in the US army in Europe. Her parents, church-going Republicans, were peripatetic after the war; her father became a furniture salesman, moving to Seattle and then Hawaii. At high school, Ann wore pleated skirts and twin sets, but was a budding bohemian and an Adlai Stevenson Democrat. In Hawaii, ‘slightly plump, with large brown eyes, a pointed chin and chalk-white skin’, she met Obama Sr in a Russian language course. When he returned to his other wives in Africa, she married an Indonesian geologist, Lolo Soetoro, in 1965. For readers interested in the early years of the forty-fourth president of the United States, his boyhood in Jakarta, in a stucco house on a dirt lane that turned to mud in the wet season, then in more comfortable middle-class surroundings, is vivid, not just for the picture of young Barry in kampong mode but for the determination of his mother, ‘ensnared and enchanted by the culture’, in the words of a friend. Obama was later reserved about his mother’s enthusiasms, but in Remnick’s telling she has her own kind of audacity. She undertook a doctoral dissertation in anthropology (on village crafts) and, after her divorce from Soetoro and her son’s return to Hawaii and the US mainland for education, worked in Indonesia for organisations concerned with the rights of women, labourers and consumers. She stares out at us bravely in a 1968 photograph. One is reminded of the Student Christian Movement and Australian women in the Volunteer Graduate Scheme in Indonesia in the 1950s and 1960s.

By the time Barack begins his political journey, the reader has been immersed in a tantalising mix of social milieux and interesting, even eccentric, people. Remnick does not try to explain Obama, avoiding the temptations of popular psychology. In the end, befitting a former reporter with the Washington Post, now editor of the New Yorker, Remnick provides a dense profile, asking readers to make their own judgement. The political core of his study is the US political system, its checks and balances, party primaries, electoral college based on winner-takes-all state voting and its human fabric of ambition, courage, risk, paranoia, lobbying and preferment.

The American presidency, like the papacy, has come to mean more than the constitution says it does, and because the electorate is so diverse – north and south, east and west, and in between a vast heartland that regards itself as the moral centre – the popular vote tends to be a blend, indeed bland. It is a curious fact that Australia’s archaic system, based on a colonial constitution, an absent, hereditary head of state and parliamentary, not popular, election of the head of government, has produced a more varied range of titular leadership than has the American system. We had Catholic prime ministers long before the Americans managed a Catholic president, Jewish governors-general and now a female prime minister (agnostic, as well) in advance of the new world icon of modernity across the Pacific.

As the Bush presidency seemed doomed, the Democratic primary contest between the first African-American and the first woman, which is a large part of Remnick’s book, became a kind of pregnancy of a new America. Some old themes, however, emerge. One of them is the surprising degree of Jewish support for Obama in the influential mix of law, business and community politics in which he and Michelle Robinson, who became his wife, were active. Another is the great American tragedy, now perhaps its romance, the legacy of slavery. Born in 1961, Obama was too young for the civil rights movement, but as a black politician he had to deal with its consequences, the assassinations of 1968, Black Power, the lure of separatism, the fears and resentments of the ‘brothers’ and ‘sisters’. He was with the movement, but not of it. He decided to be open about his mixed race, his youth and inexperience, his ‘exotic’ background. Even in the dark moments of his struggle with Hillary Clinton, he kept his candidacy on track. Another theme is money. If you are not yourself rich, you need wealthy backers to succeed in American politics. Obama is as at ease with the corporate sector, the top end of town, as he is with working families and struggle street.

Now that he is president, his world view, especially his attitude to ‘ideology’, has come under scrutiny. Remnick provides context, if not answers, drawing on Obama’s time as a student and teacher at Columbia and Harvard, as a state politician in Chicago and a national one in Washington. He detects an ‘insistent reasonableness’ in what Obama says and does. He is ‘pragmatic’, using that quality to describe what Obama called a ‘meeting of minds’ with the deposed Australian prime minister, Kevin Rudd. In 2005 Obama was a modest critic:

[The American people] don’t think George Bush is mean-spirited or prejudiced, but have become aware that his administration is irresponsible and often incompetent. They don’t think that corporations are inherently evil (a lot of them work in corporations) but they recognised that big business, unchecked, can fix the game to the detriment of working people and small entrepreneurs. They don’t think America is an imperialist brute, but are angry that the case to invade Iraq was exaggerated, are worried that we have unnecessarily alienated existing and potential allies around the world, and are ashamed by events like those at Abu Ghraib, which violate our ideals as a country.

Obama emerges as neither radical reformer nor passionate believer. On the issues of war and peace, he said in an interview for the book earlier this year, after the embarrassment of receiving the Nobel Prize for Peace, ‘[We] have to recognise that this is a dangerous world … but also that in fighting … there’s the possibility that we ourselves engage in terrible things.’ According to Remnick, he has made only a slight alteration to the Oval Office, although it was significant, replacing a bust of Winston Churchill (a gift from the British government after the terrorist attacks of 9/11) with busts of Abraham Lincoln and Martin Luther King Jr.

He has shown no sign of wanting to make fundamental changes to the economic and political system of the United States, nor of wanting to change the international system of states. His attitude to the United Nations is cautious. But he has shown a preference for the broader G20 group (which includes China and India – and Australia) over the G8 group of advanced industrial states. He has taken a stance on the reduction, even abolition, of nuclear weapons, has reached out to the Muslim world and has shown sensitivity to issues of the environment and global warming. One of the virtues of this lengthy book is that it takes account of contingency. Observers, especially academics, tend to be interested in rules and trends, ignoring the ups and downs that have to be dealt with by politicians in office. An oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, a nuclear test in North Korea or Iran, the collapse of a bank with global customers – events such as these have to be managed with the best resources available at the time. The evidence is that Obama relies on expert advice rather than on intuition or conviction but, as experts often do not agree, he has confidence in his capacity to resolve differences, so that action is possible.

In all the ways that power can be measured, the United States is head and shoulders above everyone. Its economy is the world’s largest. It spends more on arms than any other country. Its troops are stationed abroad in more countries than any other. Its air force and navy patrols the globe, and it has the most advanced satellite technology for gathering intelligence. It has more nuclear weapons than anyone else and is the only state to have used them. American popular culture permeates the world. The entire world says ‘Okay’. Many say ‘Hi’, and increasing numbers advise each other to ‘Have a nice day’. Despite its recent lapses, American business remains the beacon of best practice. Advertising in what used to be called the American manner, in other words, brashly and intrusively, is universal. ‘Market forces’, which during the Cold War were the ideological weapon of one side, are now accepted by those who once demonised them.

This combination of hard and soft power is not threatened by any other state, or combination of states, but what has driven it, the idea of American ‘exceptionalism’, is challenged in the groping for a new world order in response to issues such as the global financial crisis, climate change, refugees, terrorism and nuclear proliferation, and even old stalwarts such as poverty and war. To retain confidence in the American system, without wanting to impose it on others, a new kind of political leadership is needed; passionate patriotism is not enough. Obama may be that leader. He emerges from this examination as a person with empathy and understanding of others, unusually acquainted, as an American, not to mention an American president, with the diversity of the world. Whether it is because of the blood of an adventurous Kenyan father or a romantic Kansan mother, the mild Pacific air of Hawaii or the communal culture of Indonesia, he is at ease with the world. That in itself is a major development in American politics.

Comments powered by CComment