- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Features

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Were I Editor in Chief of The Australian for a day, the first thing I would do is can the ‘Cut and Paste’ section on the Letters page. Its schoolyard bullying of the fools and knaves idiotic enough to oppose the paper’s line – usual suspects include Fairfax journalists, the ABC, Greens politicians, Tim Flannery, and Robert Manne – lies at the heart of what stops The Australian from being a great newspaper. A favourite game is quoting a commentator saying discordant things at different times. As an argument, this is right up there with great moments in adolescent wit like, ‘You said Chanelle was a slag last week, and now you are going out with her!’

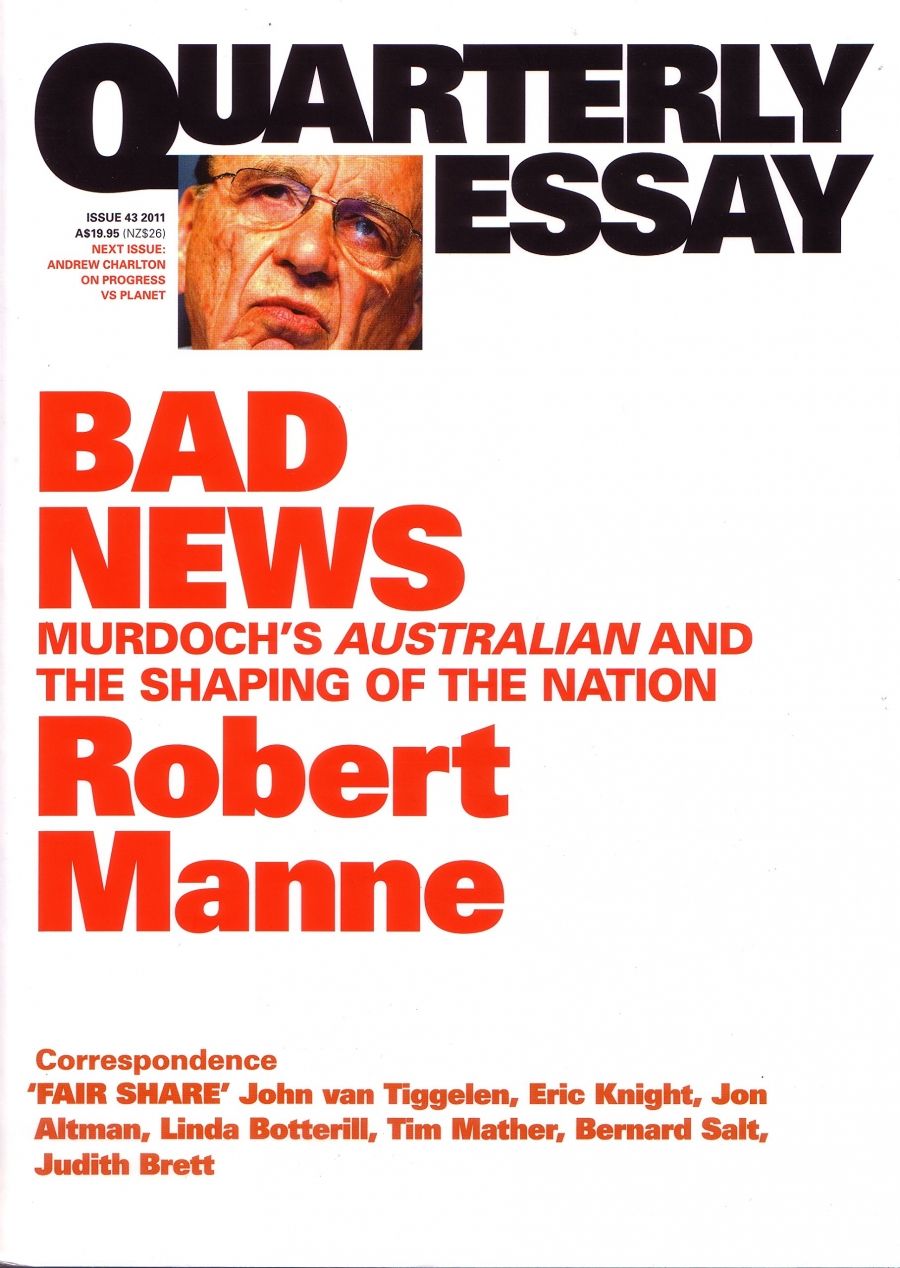

- Book 1 Title: Bad News: Murdoch’s Australian and the Shaping of the Nation (Quarterly Essay 43)

- Book 1 Biblio: Black Inc., $19.95 pb, 141 pp, 9781863955447

Even if the abuse were evenly spread across the ideological spectrum (and it isn’t), it would still be destructive sniping rather than robust debate. We have rendered politicians mute (at least in terms of thought and content) with a journalistic culture that takes everything down and uses it eternally against them. The last time John Howard thought out loud was on Asian immigration in the mid-1980s. His pronouncements were endlessly recycled against him, despite repeated denials, and he learnt never again to say anything that hadn’t been extensively road-tested with spin-masters and focus groups. Left, right, and centre have been playing the game of ‘But you said’ with increasing ruthlessness for decades. So now the ‘Cut and Paste’ standard, even for commentators, seems to be that one must spring from the womb with a perfectly formed set of convictions one never has cause or permission to vary. This isn’t deliberative debate in a properly functioning public sphere; it is a contact sport.

‘Cut and Paste’ is, for me, the clearest illustration of the juvenile vengefulness that limits The Australian. Not always but too often, the paper refuses to accept that anyone can seriously or honestly hold alternative views about economic reform, the US alliance, industrial relations, or the primacy of growth over the environment. A conviction that one’s opponents are a perverse coalition of fools and knaves (a confederacy of dunces, to quote Swift) is a bad starting point for political parties. In a newspaper, it is the triumph of opinion over journalism.

Now a defender of The Australian will complain that this is a partial reading of the paper, and I freely concede that point. There is much that is admirable, investigative, and evidence-based about the paper. To take just a couple of examples: George Megalogenis and Paul Kelly really sift the evidence, and even surprise themselves occasionally with the conclusions they reach; Henry Ergas probably is not surprised to keep discovering that the answer is freer market forces, but he makes a cogent case every time, one that requires reasoned dialogue. I have been reading the paper daily since I moved to Adelaide twenty years ago, and there is much that is admirable about it, along with the flaws.

It is the vengeful thread that hides behind the notion of ‘crusading’ that Manne reveals in his Quarterly Essay, and I hope that the paper takes account of the criticisms he makes. It is important that they do, for The Australian is the only organ in the country that has a business model for thriving as a quality broadsheet. The classified ‘rivers of gold’ that supported The Age and the Sydney Morning Herald are rapidly being diverted to the Web, and Fairfax is not diversified enough to run those papers as respect-gathering loss leaders. Something may come along to return them to robust profitability, but it is hard to see what it might be. The Australian, by contrast, didn’t make a profit at all for its first twenty years, and has never made much money. It doesn’t need to: the paper sits at the head of the Australian arm of a huge media empire, protected pragmatically by the national influence it wields (especially in federal politics) and emotionally by its place in the heart of the mogul himself.

Rupert Murdoch has not been known for his commitment to quality journalism ever since he went to London and the Sun in the late 1960s, but things were different in 1964 when he set up The Australian to shock broadsheet journalism in Australia out of its slumbers. He was deeply engaged in the new national newspaper: there are legendary stories of him on foggy winter’s mornings at Canberra airport, in his pyjamas, persuading reluctant pilots to fly the matrices of the paper out to Sydney and Melbourne to be printed. While the paper has reflected his ideological transit from the anti-Establishment left to the anti-Establishment right, it has never followed the empire’s centre of gravity down market, and appears to have privileged status in News Corporation.

A hint as to why this might be so was given in the darkest part of the recent phone hacking scandal. The father of Milly Dowler (the murdered girl whose phone was hacked by News of the World) came from an interview with Rupert and reported his description of the hacking as ‘not the standard set by his father, a respected journalist, not the standard set by his mother’. Keith Murdoch (official correspondent during World War I and manager of the Herald and Weekly Times group) has been dead since 1952, but remains a model of serious achievement for his son. Dame Elisabeth is still among us, formidable as ever, an incarnation of most of the virtues of Protestant public-mindedness. The News of the World does not reach their standards, and was expendable, but The Australian remains in many ways the sort of newspaper a striving but ultimately dutiful son would like to take home to his parents. Things will have to be very desperate before it is cast off.

Manne’s argument is not with Murdoch himself, however. He does not give in to the conspiracy theorists who see Rupert’s hand everywhere in his empire, telling editors what to say. The essay would more accurately be subtitled ‘Mitchell’s Australian’ rather than ‘Murdoch’s’, because it is the reign and bullying style of Chris Mitchell, Editor in Chief since 2002, that offends Manne. I do not mean to undermine the cogency of Manne’s evidence against some of the paper’s crusades by using the word ‘offend’. The self-serving argument led by environment editor Graham Lloyd in December 2010 that The Australian had always supported the scientific consensus that human-induced climate change is a real and serious problem is exposed to the sort of quantitative analysis of column space that blows it deservedly out of the water. Manne’s arguments have too much hard evidence to be reduced polemically to ‘opinion’. He is, however, primarily a moralist, offended by the methods and positions of an institution he strongly feels could do better with its talents and resources.

The systematic clash in this fine, if not definitive, essay is between Manne’s moralism and the rather limited ‘rationalism’ of the pointy end of editorial and opinion at The Australian in the Mitchell years. Manne’s J’accuse is summarised early on: ‘The Australian is ruthless in the pursuit of those who oppose its worldview – market fundamentalism, minimal action of climate change, the federal Intervention in indigenous affairs, uncritical support of the American alliance and for Israel, opposition to what it calls political correctness and moral relativism.’ He reprises controversies over Keith Windschuttle; Iraqi weapons of mass destruction; the pursuit of Media Watch, Julie Posetti, Larissa Behrendt, and the Greens; climate change and denialism; the making and breaking of Kevin Rudd. Clearly Manne would like a national newspaper of a different ideological colour, but the real cogency of his case lies in the exposure of a glass-jawed and bullying culture. The Australian, for all its trumpeting of freedom of speech in pursuit of its own crusades, is exposed as intolerant of other voices.

Even if half of Manne’s points were entirely fictional, the broad criticism would stand and need a response, so there is little need to argue through each of the points in detail; some, naturally, are more cogent than others, and that is up to readers anyway. We should not be overly paranoid about the influence of The Australian and News Corporation. A concerted campaign from them can wreck nearly anything they dislike, but the evidence for their capacity to achieve a positive agenda is much more slender. On industrial relations, tariffs, Aboriginal affairs, and a number of other areas of substantive policy, the paper may be able to run enough defence to stall what they oppose, but they are clearly not getting all of what they want. Nevertheless, the problem of public debate in advanced democracies at present is that nil-all is the easiest result to achieve in any contest of policy or ideas. Mitchell’s Australian can probably stop many things, but can it make much happen?

It is the national paper, with the strongest presence in Canberra politics, so its response to Manne’s calculated, substantial provocation is really important. Much depends on whether there is room for reasoned disagreement and respect for evidence in our increasingly cacophonous, opinion-driven public sphere. And the initial signs were not good. An immediate response from Paul Kelly headlined ‘Manne Throws Truth Overboard’ (14 September 2011) was followed by a double-spread on the weekend, amusingly headlined ‘A Considered Response to an Intemperate Attack’ (17–18 September 2011). This looked like the zealot’s refusal to entertain the possibility that an opponent of your views could possibly be acting in good faith. Since then, however, the vengefulness has subsided. A balanced review by Matthew Ricketson in the Review section (24 September 2011) is all I have noticed by way of direct engagement.

This could be a refusal to give a critic airtime rather than a recognition that he need not be viewed as an enemy. What I would like to imagine (and think I can detect in places) is an embryonic recognition that it is not the job of a newspaper of record to crusade at all costs. In our shrinking broadsheet market, it would be good if the healthiest specimen, and the only truly national one, recognised that we need more mutual respect in public debate if we are ever going to sort through the complex problems and opportunities that confront us. A ‘winner takes all’ mentality is neither ethical nor practical in the long run, unless, of course, you can be certain that you will never be wrong or have to review an earlier opinion. One of the things I like most about being Australian is that we have never been much given to fundamentalism.

Comments powered by CComment