- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Don Watson sits low in his chair, shy and silent when faced with a group of university administrators gathered to hear him talk about management speak – those weasel words that Watson has hunted down with grim enthusiasm. He speaks hesitantly at first, struggling to recall examples of misleading expression, evasive phrases, dishonest communication. Soon the rhythm quickens. There is indignation now in the voice, derision anew at the decay of public language. The speaker rocks forward, ranging more widely as he explains the link between thought and expression. Jargon hides intentions. Clichés abandon serious engagement with an issue. This is not the pedant’s obsession with grammar, but anger when the contest of ideas is undermined by impenetrable language.

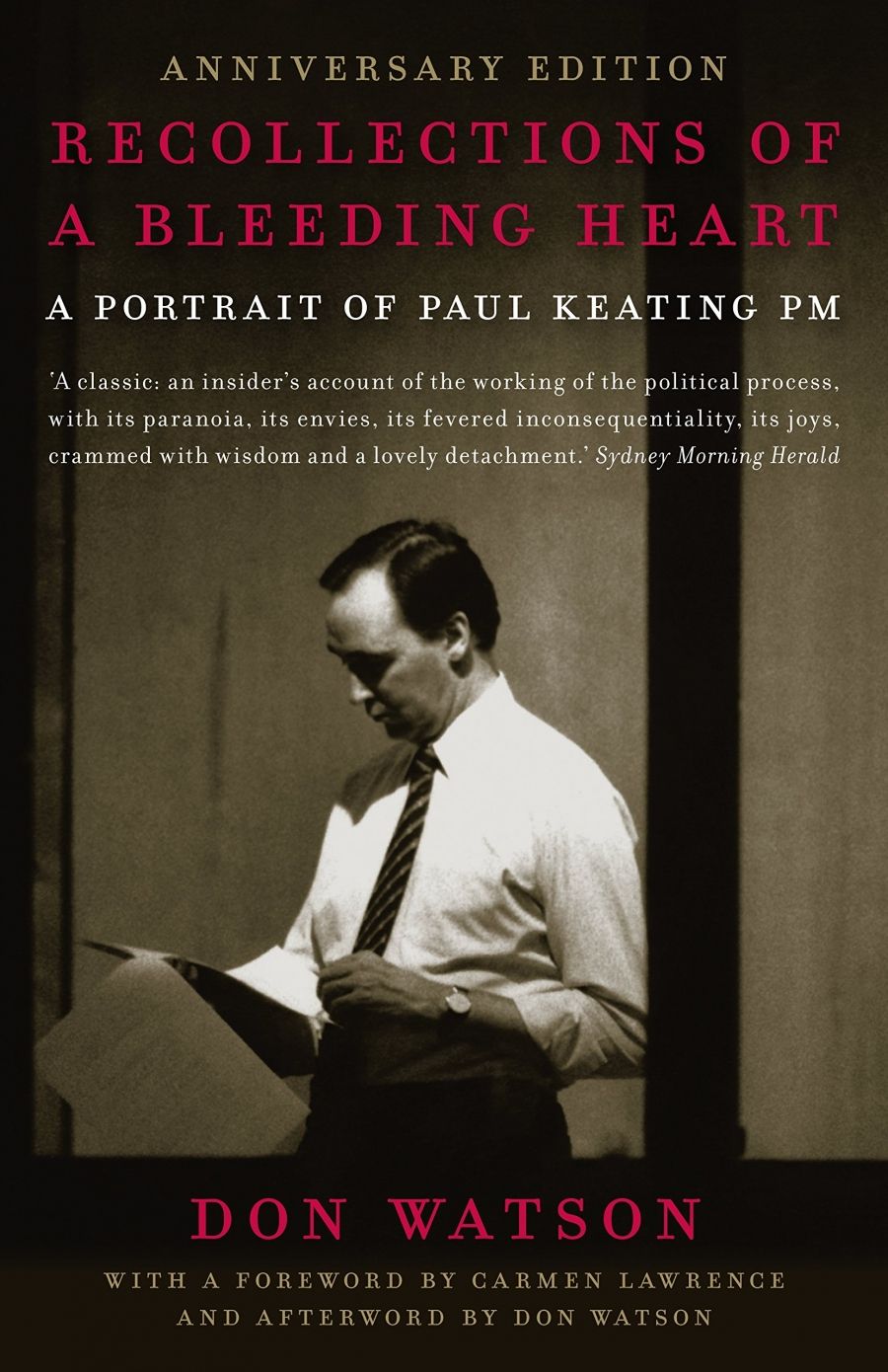

- Book 1 Title: Recollections of a Bleeding Heart

- Book 1 Subtitle: A Portrait of Paul Keating PM, Second Edition

- Book 1 Biblio: Vintage, $29.95 pb, 801 pp

Words matter to a professional speechwriter, as they seek to shape and influence opinion. Great political speechwriters – Ted Sorensen for John Kennedy, Peggy Noonan for Ronald Reagan and George Bush Sr, Graham Freudenberg for Gough Whitlam and a slate of Labor premiers, and Don Watson – know that reality is malleable. Expressed in the right order, delivered with conviction, ideas can alter the contours of society. When Paul Keating stood to deliver the Redfern Park speech on 10 December 1992, using only the words that Watson wrote, Keating’s delivery made the speech his own. By addressing these concerns in this place, by using the authority of the prime ministership to signal that reconciliation must be the nation’s business, Keating changed the public conversation. Despite all the disappointments since, the Redfern conclusion – that we bear collective responsibility for Indigenous outcomes – has endured.

The relationship between writer and speaker can be intense. To write convincingly for someone, you must understand the person and his or her program. To draft a speech is to give form to ideas perhaps still inchoate for the leader. Indeed, voices may become indistinguishable. National Reconstruction was the title of a 1990 collection of speeches credited to Bob Hawke. The pages captured succinctly the program of national consensus and economic liberalism championed by Hawke as prime minister. His speechwriter Graham Freudenberg not only wrote all the content, but also penned Premier Neville Wran’s Introduction to the book.

The speechwriter works in the shadows. Watson calls this ‘the contract’ – the ‘common understanding that political leaders own their speeches regardless of who writes them’. It is the politician who takes responsibility for the words and their consequences. The leader’s additions, amendments, revisions, and changes mid-flight take ‘intellectual and political possession of speeches’, says Watson. His account of the Keating years is, in part, the relationship between writer and speaker. The first edition closed with an acknowledgment to Keating for ‘inspiration and rare generosity’. Keating did not reciprocate. For him, the publication, with its personal revelations and private glimpses,broke that contract. Keating fulfilled a commitment to speak at the book launch and then, a single sour phone call a few years later aside, cut all contact with Watson.

The rift clearly hurts. Watson’s Afterword, a welcome addition to this tenth anniversary edition, defends the book as overwhelmingly affectionate, fair, and consistent with his original engagement by Keating. In difficult moments, Watson would warn his colleagues – and the prime minister – ‘just remember, I’m writing all this down you blokes’. In Watson’s judgement, the contract stands. For Keating, writing this book was a form of betrayal, revealing moments that belong only to the participants. The former prime minister, aggrieved, described his speechwriter as a bat, returning always to the dark to feed.

This is an argument we readers cannot join. In her perceptive Introduction to the tenth anniversary edition, Carmen Lawrence notes the strain between two former allies, and hopes for reconciliation. She sees Recollections of a Bleeding Heart as a ‘complex, sculptured and vivid portrait’ of ‘a man worth knowing’, and hopes Keating might one day revisit the account. Yet few subjects are happy with biography. As Watson told ABC Radio, ‘None of us like to be written about. We all feel traduced by anything that’s said. That’s one of the advantages of being dead at your funeral – you don’t hear what people make of your life.’

On its original publication, Recollections of a Bleeding Heart gathered numerous prizes and glowing reviews (Neal Blewett reviewed it for ABR in June–July 2002). A decade later, it should do so again. Watson’s account is now an Australian classic, and is offered substantially unchanged, with the addition of a brief Introduction and Afterword. Here is a chance to reread Watson’s detailed, and subjective, account of the Keating prime ministership from 1991 to his defeat in 1996. Watson is partial in several senses; in awe of someone he liked instantly on first meeting, drawn both to Keating’s vision and underlying melancholy – and partial because the picture is incomplete. As a member of the Prime Minister’s Office, Watson did not see Keating in key settings such as cabinet, when the politician became the policy maker, dealing with the challenges facing any national government. As Keating observed, the book is a dialogue with just the pilot, leaving out the crew and passengers.

Despite these limits, the book remains the most cited work on the Keating years – a testament to its vivid depiction, even if viewing a prime minister through the narrow prism of his political office. Keating’s rebuke at the launch – that Watson was a black box, dutifully recording everything that happened, but unable to distinguish the important – stings, but has not deterred readers. Watson prefers the metaphor of a hand-held camera, able to capture office arguments between humanist ‘bleeding hearts’ such as himself, and the sharp economic mind of Don Russell, the ‘pointy head’. Neither description approaches the reality. There is more art, more skilled shaping of the account than the form suggests. It is Watson the historian, and occasionally Watson the satirist, that frame the compelling observations, while Watson the writer turns diaries, scribbled, exhausted, on flights to Melbourne, into memorable prose.

What lessons should we draw a decade after publication? In her Introduction, Carmen Lawrence regrets the continued degrading of political debate – the emphasis on image and personality, policy through focus groups, the absence of ideas. Watson picks up the same theme in his Afterword. Keating, he argues, has been replaced by a generation of Labor leaders who ‘discard big picture politics for poll-driven caution’, turning their back on a Labor movement of ‘spirit and character’ for the ‘anaesthetising grip’ of contemporary political practice. Keating’s forays onto Lateline provide a vivid reminder of his skill with word pictures and his ability to explain complex economic forces through striking metaphors. His story lives on stage, touring for the nation’s true believers. Yet to work as satisfying theatre, Keating! The Musical changed the ending – the hero was not rejected by the electorate in 1996, but triumphs over John Howard. Those Labor leaders who followed Keating faced a more sobering truth about how the Australian electorate responds to reforming prime ministers.

Reflecting on the reissued Recollections of a Bleeding Heart, commentators have urged Keating to write his memoirs. Watson calls Keating ‘the greatest storyteller Australian politics has ever seen’, but Keating has yet to tell the story he knows best. As John Howard demonstrates with Lazarus Rising (2010), the public seeks firsthand accounts of our shared lives and times. Though Keating has been dismissive of the traditional memoir, as of other honours offered former national leaders, he must live with Recollections of a Bleeding Heart as the record until he decides to write. Should Keating sign his contract, I suspect that Don Watson would be a willing co-author, keen once again to enjoy the intense, if fractious, relationship that bind leaders and speechwriters, words and action.

Comments powered by CComment