- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Jamie Mackie’s recent death was a sad reminder of a time when enthusiasm for Asian studies mirrored the Australian government’s developing perception that the future lay in ‘our’ part of the world. The small cohort of academics who initiated these studies were genuine pioneers. For instance, Mackie, in the decades after 1958, became founding Head of Indonesian Studies at Melbourne University, founding Research Director of South-East Asian Studies at Monash University, and founding Professor of Political and Social Change in the Pacific and Asia at the Australian National University. Prior to World War II, there had been virtually no Asian studies in Australia. Now the field was wide open for those who were skilled and interested, and Herb Feith was among the earliest.

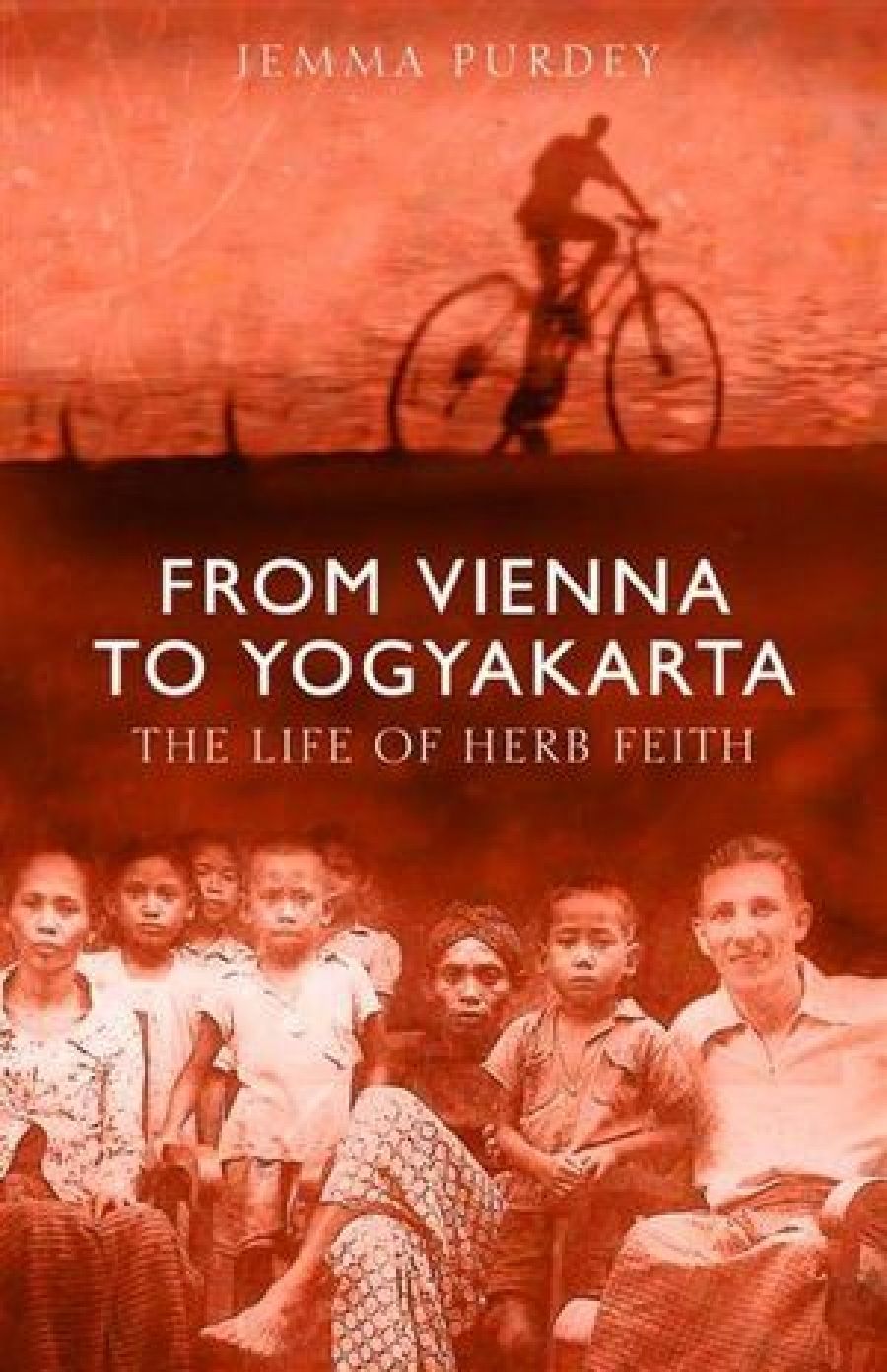

- Book 1 Title: From Vienna to Yogyakarta

- Book 1 Subtitle: The Life of Herb Feith

- Book 1 Biblio: UNSW Press, $69.95 pb, 576 pp

It was the war that first brought people such as political scientist William MacMahon Ball and entrepreneur Kenneth Myer into contact with Asia, and led them to promote the study of Asia’s cultures and languages as a foundation for our postwar role. At Melbourne University, ‘Mac’ Ball brought Asia into International Relations, while, at Ken Myer’s instigation, the Myer Foundation funded the inaugural Oriental Studies Department.

Scholarship and student interest developed so rapidly that by the mid-1990s the Asian Studies Review reported a total of fifty-five Asian Studies Centres across Australian universities. Monash University taught Thai, Lao, Korean, and Hindi, in addition to the more usual Asian languages, and its Centre of South-East Asian Studies was the primary Australian focus for Indonesian scholarship. Many Australian secondary, and even some primary, schools were enthusiastic about ‘our Asian future’, and offered students Chinese, Japanese, or Indonesian, in addition to the usual European languages.

The changed passions and priorities of the last twenty years have undermined such initiatives. Especially disturbing is the big decrease in those schools that offer Asian languages. But a much reduced group of Australian Studies Centres still exists, thanks to the continued involvement of dedicated teachers and students, and Australia’s international reputation among Asianists remains high.

At the start of all this was Herb Feith (1930–2001), the first Australian student volunteer in Indonesia, whose sympathetic biography by Jemma Purdey is the first major assessment of his life and work. As she reminds us, Feith’s stature in the Asian Studies community and beyond is due not only to his intellectual accomplishments, but also to his human qualities, which moved him to direct personal involvement, often to the detriment of his health and emotional equilibrium. Meeting Herb wheeling his bicycle across the Monash campus, his base from 1961, was always an arresting experience. It was impossible not to be drawn by the feeling that you, among all the people in the world, were the person he was most delighted to see, and to sense that this was not artifice, but a recognition of our mutual humanity.

Herb’s distress about human inequality was partly fuelled by his early experience as a displaced person. Born in Vienna into a middle-class Jewish family, he arrived in Melbourne at the age of eight and began the first of his many cultural adjustments. An only child, he was devoted to his parents, who imparted a sense of obligation not only to them but also to humankind: ‘a terrible lot was expected of me. Basically I was expected to make the world into a better place.’ His parents were intellectually and practically engaged in his activities, their pride only tempered by concern for his health and, in his mother’s case, by disappointment that Herb never embraced the more religious aspects of Judaism. He called himself a ‘syncretistic Jew’, the syncretism including the Student Christian Movement, Quakers, and Buddhism, in an attempt to learn to ‘live religion in the plural’. As a secondary student and member of the United Nations Club, he had already embarked on charitable activities, cycling around Melbourne’s eastern suburbs collecting money for impoverished postwar Europe. Along the way he met his similarly engaged future wife, Betty, an ardent Methodist. Their intertwined lives and careers afforded Herb his greatest strength and security.

It was as a political science student of Mac Ball in 1949 that Herb became aware of South-East Asia, and Indonesia in particular. Its struggle against the Dutch colonisers was a lively issue in Australia, and Herb was fascinated both by Mac’s tales of visits to this exotic neighbour, and by journalist Douglas Wilkie’s enticing reports in the Melbourne Sun.Herb sought out Wilkie, who told him about Molly Bondan, an Australian who was married to an Indonesian, who, like her, worked for the Indonesian government. Herb’s letter to Bondan initiated a lifelong friendship.

With ideas from Molly, Betty, Mac Ball, the Student Christian Movement, and a call by Indonesian students for technical assistance from overseas, a plan evolved for a Volunteer Graduate Scheme under the auspices of the National Union of Australian University Students (the Australian government agreed to pay fares, insurance, and the cost of a bicycle). In 1951 a scholarship for MA research led to Herb’s first visit to Indonesia. After some hesitation, the Indonesian Ministry for Information offered him two years’ employment under Molly’s supervision, as a civil servant on a local salary. He then started language lessons at the Indonesian Consulate in Melbourne. With such small steps began the tradition of student volunteers and Herb’s life work. His MA thesis was the first major Australian scholarly work on post-independence Indonesia.

The names of the first generation of Australian Indonesianists and their international colleagues resound throughout the book. Jamie Mackie, also under the influence of MacMahon Ball, stopped on his way to Indonesia in 1957 to visit a young John Legge (Sukarno’s first biographer [1972]), who had just returned from study at Cornell University’s Modern Indonesia Project. Founded in 1954 by noted Indonesianist George Kahin, it became a second home for young Australian scholars, including Herb.

From Vienna to Yogyakarta is as much a primer on Indonesian politics as an account of Herb’s development, the two being inextricably linked. His struggles with political theory, his growth as a writer and as a much-loved teacher in the Monash Politics Department, his despondency at the decline of constitutional democracy in Indonesia (the title of his seminal work [1962]), his close relations with Indonesian friends and his insistence on living at their economic level, the growth of his family, and his international reputation, all make absorbing reading. Purdey tellingly interweaves the parallel story of how the intensity of his emotional commitments led to increasing depression and illness and to his eventual abandonment of Indonesia as his core focus, as Ivan Illich’s strong influence attracted him towards peace studies and local and international activism. Feith’s lifelong struggle was, as he put it, a conflict of ‘mind versus heart, theorizing versus action, professional work versus deconditioning, critical versus liberating’.

Herb’s shocking death on his bicycle at a Melbourne railway crossing in 2001 deprived Australia of one of its most remarkable individuals. Had he lived longer, he might have found solace in the renewal of Indonesian parliamentary democracy.

Comments powered by CComment