- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

What to do with Whiteley? Forget the gutsy audacity and visual energy; in Bernard Smith’s estimation he was ‘egocentric, pseudo-profound and self-pitying’ (Australian Painting 1788–2000). Smith could not abide Whiteley’s ‘incapacity for detachment’; his cult of personality, poured into every last crevice of his work. With the hegemony of the social and theoretical construction of art, the actual person of the artist has been an increasing problem for art critics. Whiteley’s work, driven by personality and fuelled by sensation, is easily viewed as a romantic indulgence.

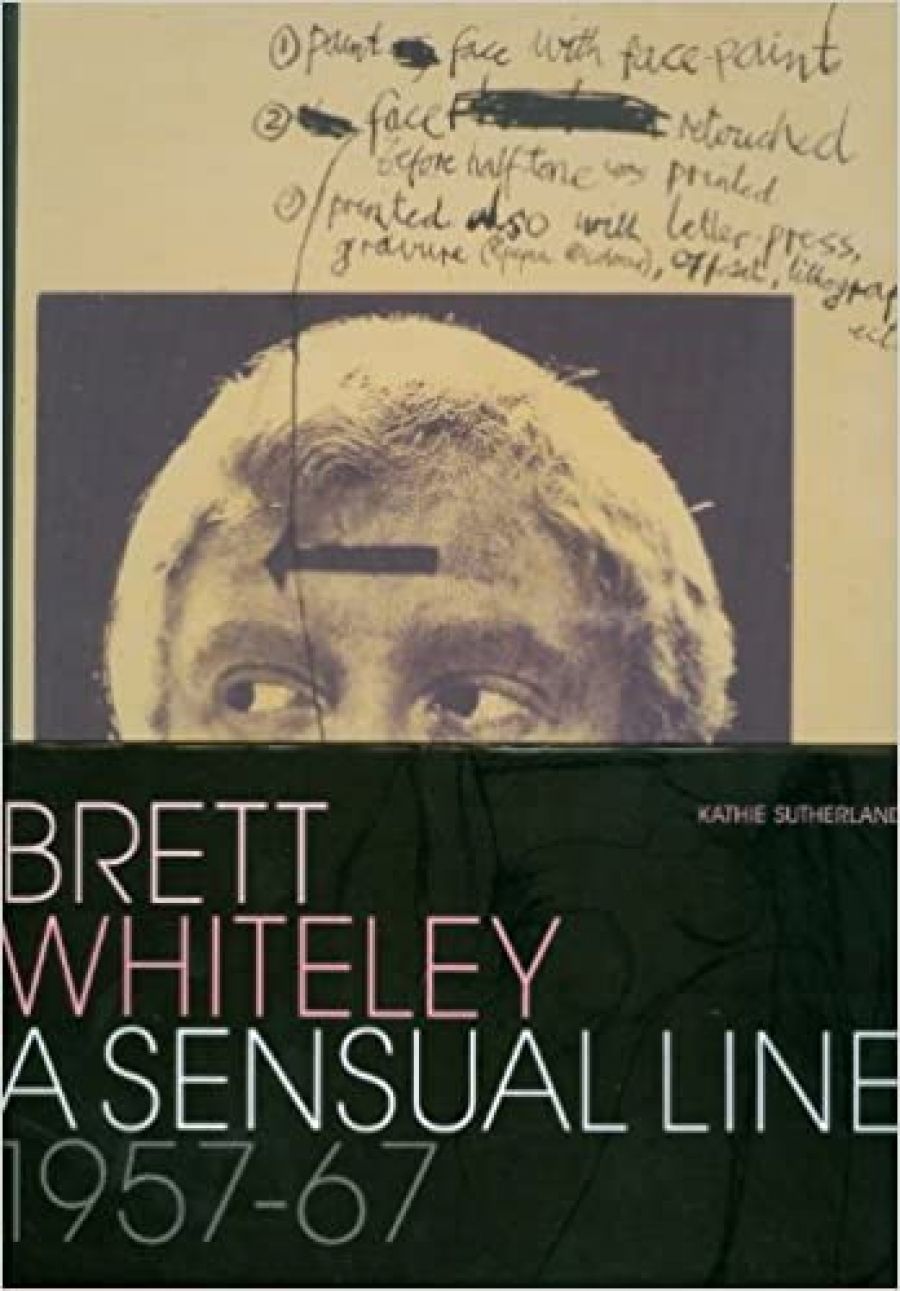

- Book 1 Title: Brett Whiteley

- Book 1 Subtitle: A sensual line 1957–67

- Book 1 Biblio: Macmillan Art Publishing, $130 hb, 342 pp

Brett Whiteley has attracted more monographs than most Australian artists; and almost all – from Sandra McGrath’s biography (1979) to Barry Dickins’s almost hysterical prose (2002) – include large doses of personal memoir. Sutherland’s new addition may be justified on the basis that it attempts a more objective account alone. Focused on the early years between 1957 and 1967, she prefers to concentrate on the art rather than on the life. The book itself, however, emits the aura of celebrity; large and glamorous in black, pink, and yellow, with a wrap-around cover. With its attractive and entertaining visual mix and wealth of images, it has a number of the virtues, but also most of the faults of current graphic design. The toughest for the reader is the small, pale grey, sans serif text, virtually invisible quotation marks, uneven columns of text, and the arbitrary interruption of the text by large-scale illustrations. Under these conditions, Sutherland’s argument and themes are not easily followed. There is also an absence of comparative visual material, which is a special loss given the extent of artistic influences on Whiteley’s development.

Against these odds, then, we follow Sutherland’s trail through Whiteley’s mercurial career over its first, white-hot decade. His development is simultaneously an art historian’s dream and nightmare, with an over-supply of documentation, controversies, and artistic milieux. He soaked up multifarious influences, wrung them out in his own distinctive manner with a Bob Dylan-style stream of consciousness commentary. We learn of, but unfortunately do not see, numerous formative influences from Lloyd Rees to Bonnard and Bacon. Interviews with Wendy Whiteley reveal fascinating aspects such as the source of the warm tomato red of the works painted in Florence and Siena in barrels of ancient tempera pigment obtained from a local art shop. In patiently accumulated detail, Sutherland charts the evolution of his characteristic body-as-landscape visual habits from early anthropomorphic ‘clefts and protuberances’, culminating in the sensuous rhythmic body masses of the Bather series, 1962–64.

Sutherland’s approach is sound, clear, and complex in the range of material feeding into analysis. She deploys a classically progressive historical model, declaring in her introduction that her underlying mission is to show that a ‘continuous progression and interrelationship of ideas shaped Whiteley’s approach to form during the years 1956–65’, and that ‘the catalyst for change and progression was expatriation’, his travel to Europe and Britain. These are laudable, if somewhat predictable, themes based on squeaky-clean art-historical methods. Yet this is an artist whose work demands debate over an array of issues: aggressive vulgarity, sensationalist use of popular culture, hero-worship of van Gogh, Dorian Gray-style self-projections on Rembrandt’s self-portraits, wild declarations on politics, identification of the human and animal in the inspired Zoo series, submersion in drugs, manipulation of the female body, to list just a few.

Indeed, it is impossible to confine the most important challenge for the interpreter of these ten years to pure art history: how to move from the idyllic hedonism of the bathers to the Christie series of 1964–65. John Christie committed a number of horrific rapes and murders from 1943 to 1952, in a small grimy flat in Notting Hill. Obsessed with the grisly details, Whiteley researched the cases and visited 10 Rillington Place, where the murders occurred. His depictions are disturbingly seductive, and Whiteley himself worried about their relationship with the evil depicted. For most critics, including Sutherland, the Christie series manifests the duality of Whiteley’s persona, his fascination with evil and with reconciling opposites in human nature, under the influence of writers such as the psychiatrist R.D. Laing (The Divided Self),and Colin Wilson (The Outsider). She connects Whiteley’s impressive portrait of Christie with Hannah Arendt’s idea of ‘the banality of evil’ and argues for the impact of art incorporating violence, including an exhibition of Goya’s Disasters of War, which had opened at the Royal Academy in 1963, and, above all, the works of Francis Bacon.

Sutherland engages in a number of well-informed and exploratory discussions. Indeed, she identifies Whiteley’s dual personality and his sexual and sensual traits as a ‘sub theme’, although analysis of such ideas is not developed in its own right and remains mired in her chronologically driven narrative. But she brings a new seriousness and academic clout to her subject. Besides its glorious images, the book provides abundant documentation, including a list of exhibitions and an excellent catalogue raisonné, which lays the foundation for future debate about the many issues raised by this most lively of artists. For all his faults, Whiteley was articulate, unafraid of ideas and in touch with his times. Even Smith concedes a ‘moral grandeur’ to his efforts. Above all, Whiteley could draw, a technical facility that gave rise to the sheer swooping, leaping vivacity of his high-velocity vision. His disturbing failures of taste, of which there were many, can nevertheless be interesting. His successes are among the most exuberant and adept of twentieth-century Australian art.

Comments powered by CComment