- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

‘I kept thinking: if his face looks like this, what must his balls look like?’ David Hockney’s assessment of the craggy countenance of W.H. Auden is clipped and convenient, but I suspect Auden would have been far more interesting on the subject of sitting for Hockney. Given the concentration and quality of the encounters between English portrait painters or sculptors and their subjects, it is slightly odd that more writers have not published accounts of the experience of sitting for their portrait.

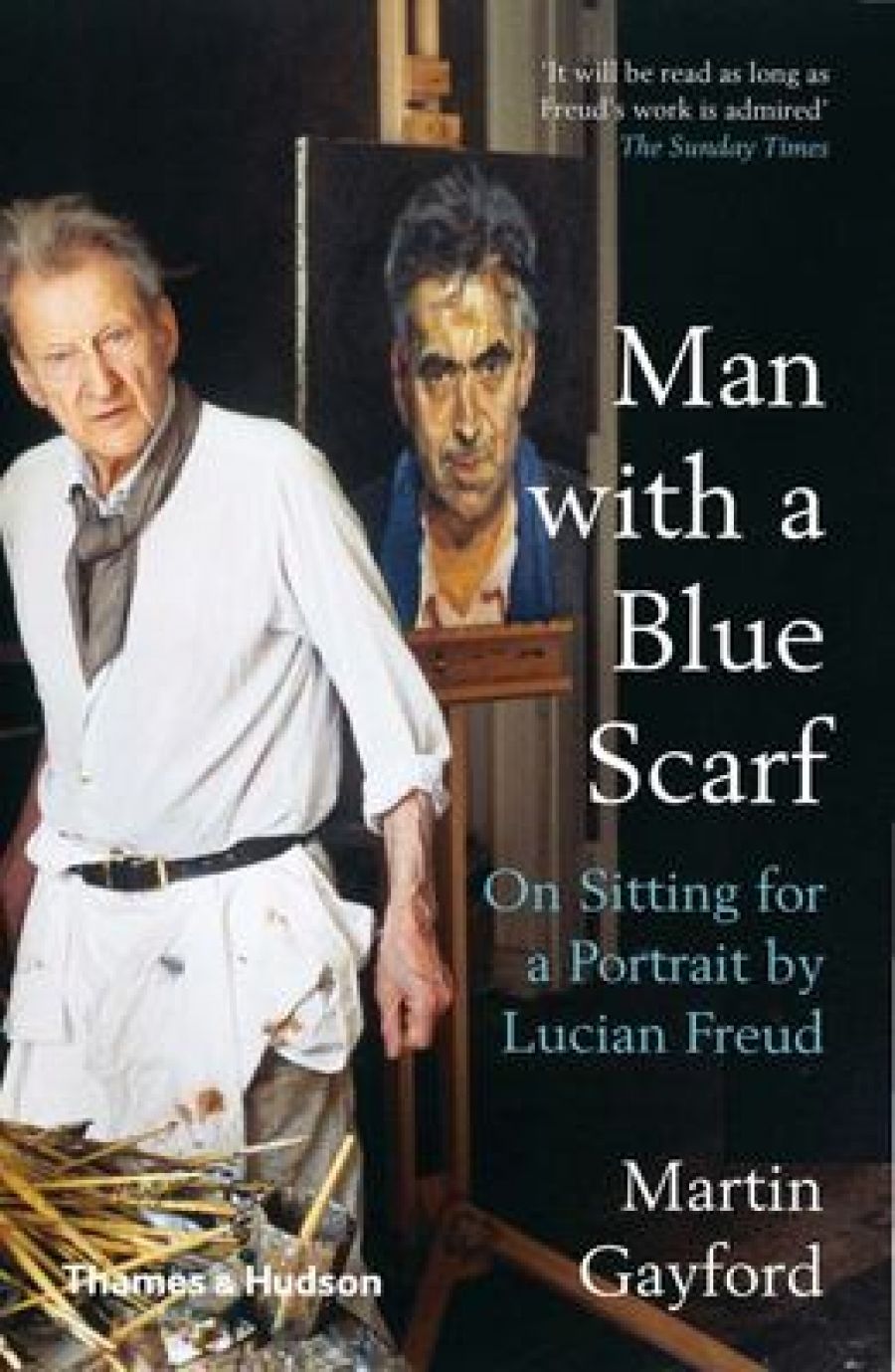

- Book 1 Title: Man with a Blue Scarf

- Book 1 Subtitle: On sitting for a portrait

- Book 1 Biblio: Thames & Hudson, $49.95 pb, 237 pp

Think of the possibilities: Alexander Pope on Louis-François Roubiliac (clever); Sir Joshua Reynolds on himself (pompous); Warren Hastings on Sir Thomas Lawrence (urbane); John Ruskin on George Richmond (bossy); Charles Dickens on Daniel Maclise (chatty); Cardinal Newman on John Everett Millais (perhaps tormented by the sin of pride); Oscar Wilde on William Powell Frith (witty); Daisy of Pless on the Lafayette studios (dotty); Henry James on John Singer Sargent (long-winded); T.S. Eliot on Wyndham Lewis (guarded), Einstein on Epstein (complicated), Winston Churchill on Graham Sutherland (terse), and so on. In the 1960s the memoirist James Lord wrote a detailed account of sitting for Alberto Giacometti, but apart from that I cannot think of any other book that resembles this fascinating account by Martin Gayford of the lengthy process of sitting for Lucian Freud.

Sitting or posing for a painter ought to be compulsory for students of art and of the history of art, because nothing gives you a faster, fuller, or better insight into the complex enterprise of studio portraiture than collaborating in the fabrication of your own. Lately I have had this experience, thanks to the generosity of my colleague Jonathan Weinberg. Notwithstanding the easy flow of conversation back and forth between the easel and the couch, I was struck by how intensely soporific it was to pose more or less motionless for at least several hours at a time. Ipso facto, do all subjects of portraits end up looking sleepy? Evidently, had I attempted what Gayford has achieved, I would never have managed to stay awake long enough to keep track of the process, or to take careful note of the painter’s train of thought. As it applies to a genre that is so central to the recent history of art, that process is remarkably under-studied.

The dispassionate, sometimes even coldly reductive observations made by a portraitist are thoroughly intertwined with the emotional ping-pong of artist and sitter, every bit as much as leaves, stems, buds, and tendrils enmesh in a Morris wallpaper. Much of the time, those observations simply cannot be described as objective. The portraitist is observing you observing him observe you. He is a searcher out of imperfections, the documenter of crease and jowl, the enquirer into your frame of mind. He may well be a flatterer, or else a curmudgeon – any sort of aesthetic disengagement is impossible. The merest mention of the large mole on your cheek can generate an uneasy intake of breath, and a slight adjustment to the position of your chin. A new and different contour becomes apparent. It is complicated, because what the painter sees is both a process of accumulation, and of playing musical chairs with your bits and bobs on his jealously guarded paint film.

Auerbach famously scrapes everything off the canvas at the end of the working day, and starts afresh at the next sitting; the finished painting is what is left at the end of the very last session – a tacit acknowledgment of the ancient Chinese principle that the accumulated culture and experience acquired by an artist in the course of a lifetime ought to be contained in a single brushstroke. From the outset, Freud and Gayford’s enterprise must have been complicit, not merely collaborative; I doubt that Freud would have undertaken it without approving of Gayford’s plan to write a book beforehand. Inevitably, therefore, what we get is the product of what both men are prepared to reveal about the nature of their unscripted performance.

Old artists are not usually in a hurry, and Freud certainly takes his time: The Queen sat for him upwards of twenty-five times, but Gayford sat for him no less than forty times in 2003–04, and inevitably the work slowed to a snail’s pace when the conversation got lively. That is actually the reverse of my own experience, which was that when the talk sped up so did Jonathan’s brushwork. Freud describes his personal taste as ‘floorboard-ish’, and there is something of a monastic seclusion in his top-lit London studio surroundings. Though spry, at times Freud seems nervous, sometimes working ten hours a day, between baths. If the artist is on edge, so is his subject. How will it turn out? Effectively, how long must Gayford put his life on hold before the picture is finished?

Queen Elizabeth sits for Lucian Freud. Photograph by David Dawson, 2001.

Queen Elizabeth sits for Lucian Freud. Photograph by David Dawson, 2001.

Lucian Freud can be a spiky man. I once wrote to him about his superb early head study in Adelaide, which was purchased for the Art Gallery of South Australia upon the recommendation of Kenneth Clark – the first painting by Freud to enter the collection of a public art museum. Some months later I received a postcard with the slightly unnerving message: ‘I don’t much like the painting. It is rather lopsided.’ Gayford captures a similar propensity to downright crotchetiness, along with an odd array of opinions and stories. Freud hates Leonardo; the Mona Lisa is awful. D.G. Rossetti is the nearest that painting comes to the condition of bad breath. Picasso was intellectually dishonest, and Matisse was a lot better. The nude is a human animal. Francis Bacon once booed drunkenly while Princess Margaret sang a song. Portraits require a bit of ‘poison’.

Freud’s hero is Titian. He knows he has finished the job when it begins to feel as if he is painting another artist’s picture. (The perfect follow-up question: Which artist?) At one point Freud mentions an incident when, as a young man, he served in the merchant navy during the war, and a convoy returning from Nova Scotia was attacked by Germans. A vessel following his own was blown to pieces, and body parts and wreckage rained down on all sides. Recently, I asked another old painter, John Hoyland, about his experience of the bombing raids on Sheffield in the industrial north. He told me his mother didn’t like to take John and his sister into the air raid shelters because of all the screaming and wailing – they were both little. There is more trauma and less stiff upper lip in all of that than the Ministry of Information was ever prepared to acknowledge. At enormous peril to herself and her children Mrs Hoyland, who is still alive, preferred to turn the nightly raids into an adventure: chocolates under the bedclothes.

Freud is older, but the sense of displacement was for him, if anything, the greater – escape from Vienna, a strange new country and language, world war, rubble, and body parts. No wonder there is in Freud’s approach to flesh more than a suggestion of slab and charnel. You do not have to stretch a very long bow to grasp how the anxiety and fear experienced by the child were parents to the artist, and there is on top of everything an elephant in the room off Bayswater Road: Lucian Freud’s psychoanalytical grandfather – not the lightest of dynastic burdens to carry, especially in our time and at Freud’s advanced age.

According to Thames and Hudson, ‘Man with a Blue Scarf is a book unlike any other: the inside story of how it feels to pose for a remarkable artist, and to be transformed into a work of art.’ Martin Gayford is, of course, a critic and not a work of art, but his account of the creation of his portrait is valuable, nuanced, frank, and entirely absorbing.

Comments powered by CComment