- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Features

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

During the Cairns Indigenous Art Fair (CIAF) held this August in far north Queensland, the city was buzzing with the visit of many of the country’s leading contributors to contemporary indigenous arts and culture. I ran into some of the most significant visual, performing and literary indigenous artists and arts professionals, many with hereditary links to the region, such as internationally renowned artists Vernon Ah Kee, Ken Thaiday Sr, and Daniel Boyd, and leading arts advocates, mingling with emerging artistic practitioners.

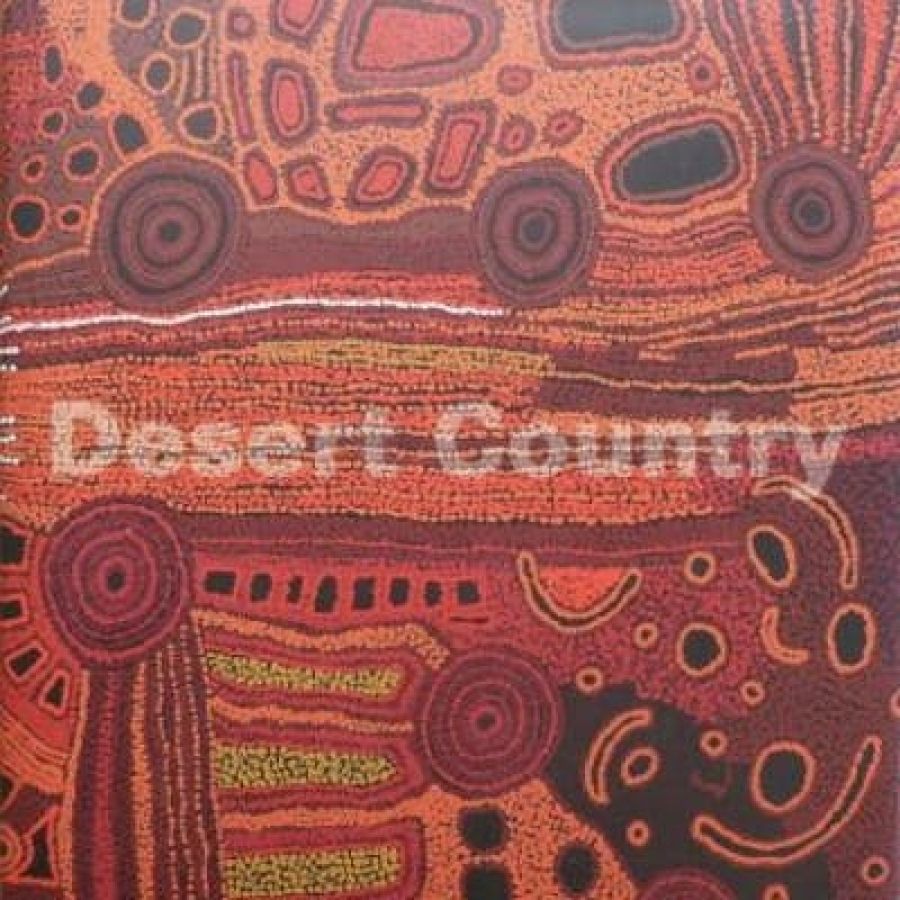

- Book 1 Title: Desert Country

- Book 1 Biblio: Art Gallery of South Australia, $80 hb, 216 pp

- Book 2 Title: Yiwarra Kuju

- Book 2 Subtitle: The Canning Stock Route

- Book 2 Biblio: National Museum of Australia Press, $59 pb 255 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Cover Path (no longer required): images/1_SocialMedia/2021/August_2021/META/yiwarra-kuju-the-canning-stock-route_view2_1200px_2ca28265-9816-4cb6-9e11-56bdc9f64eaa.jpg

One of the guest presenters at the CIAF symposium had travelled farther than most of those in attendance. Rebecca Hossack, whose gallery of the same name, located in central London, was instrumental in promoting indigenous visual art to British audiences at a time when what is now considered the quintessence of Australianvisual international representation, indigenous art and culture, was principally unknown beyond the ethnographic academy.

An Australian expatriate, Hossack was seduced by The Songlines (1987), the influential publication of celebrated British author Bruce Chatwin’s travels through central Australia in the 1980s. The idiom ‘Songlines’ became synonymous with all things Aboriginal, rather like ‘The Dreaming’, and Hossack used it to promote her annual exhibitions of contemporary Aboriginal art. She was the first to showcase the exceptional work of Papunya Tula alumni, the late Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri. She also presented him to Queen Elizabeth, which generated the newspaper headline ‘Big Black Artist meets Great White Queen’. A more uncertain enterprise was presenting the critical social documentary photographic work of indigenous auteur, the late Michael Riley.

At CIAF 2010, Hossack recalled that when she began her career in the indigenous visual arts and cultural sectors, there were extremely limited reference materials on the fledgling art movement to edify intrigued but fundamentally untutored viewers. People may have been enthused by the (flawed) writings of Chatwin’s twentieth-century ‘grand tour down-under’, but many had little idea how to ‘read’ contemporary Aboriginal art, other than at a superficial level. However, in 2010, Hossack mused that the quantity of publications on all aspects of indigenous art produced over the past twenty or so years could possibly fill one of the former oil tanks now home to CIAF as the Tanks Art Centre – though we had reservations about some books’ quality.

Herein lies the conundrum. What sources does the discerning viewer–reader select in order to transcend the limiting Western constructs of ‘traditional’, ‘urban’, and even ‘contemporary’ indigenous visual art and culture? Due to the magnitude of individual artists and movements – continually developing throughout the country since first colonial contact in the late 1700s, and arguably even earlier, through cultural exchanges with Macassan, Chinese, and Dutch visitors, among others – no single tome can adequately cover all these aspects.

Albert Namatjira, Illum-Baura (Haasts Bluff), Central Australia, 1939, watercolour on paper, 34.9 x 52.7 cm, Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

Albert Namatjira, Illum-Baura (Haasts Bluff), Central Australia, 1939, watercolour on paper, 34.9 x 52.7 cm, Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

However, there are many excellent publications on specific projects and topics, and further knowledge can be gained through one’s own research. Two recent publications offer distinct vignettes into this complex, profound world. They mirror the diversity of contemporary indigenous art and culture in the twenty-first century, while sustaining inextricable connections to an ancient ancestral past. Yiwarra Kuju: The Canning Stock Route, published by the National Museum of Australia Press to coincide with the Museum’s co-curated exhibition of the same name, and Desert Country, which accompanies an exhibition of works from the collection of the Art Gallery of South Australia (AGSA), are vital additions to the compendium of existing texts on Aboriginal art in Australia, for different grounds. (Both exhibitions are on display until 26 January 2011; Desert Country will then tour nationally.)

Of these, Yiwarra Kuju is more likely to engage readers. The subtitle, The Canning Stock Route, is a McGuffin, in that the narratives – visual and literal – included within the book cover complex aspects of cultural life and belief structures for Western and Great Sandy Desert peoples associated with the Stock Route, revealed in a spectacular visual lexicon. The dark and light aspects are noted: the mutually beneficial cultural exchanges and the cruelly punitive colonial shocks that still resonate across and through communities today. One man’s folly, or, more fittingly, a government imposition which generated irrevocable access to lands previously safeguarded by lack of contact, unintentionally created the setting for the birthplace of superb indigenous visual representations that documented shared cultural archives.

Desert Country, eagerly awaited by this reviewer, is the first major publication overseen by the inaugural indigenous curator of Aboriginal art at the AGSA, Nici Cumpston. AGSA holds the paradoxical record of being the first fine art museum to acquire a work by an Aboriginal artist as a work of art – Illum-Baura (Haasts Bluff) by Albert Namatjira (1902–59, Western Arrernte) – and the last state public cultural institution to create a specified position to oversee the indigenous collection, let alone an indigenous-identified position. While neither book is revelatory in terms of design, both satisfy the status quo of contemporary indigenous visual art.

This reviewer was fascinated by anthropologist Kim Akerman’s remarkable depiction of the actual, inefficient route overlaid by myriad customary Dreaming/Ancestral pathways. In conjunction with the painting by Clifford Brook, the nephew/son of revered, if de facto, Canning Stock Route affiliate, Rover Thomas (c.1926–98, Wangkajungka/Kukatja peoples), Blood on the ground, Wells 33–41 might have been better placed on the cover as the point of entry for readers, providing them with an embracing visual and metaphorical construct.

Likewise, within Desert Country, it would have been good to see a reproduction of that work by the great Namatjira, whose spirit resonates in all contemporary indigenous artists, represented in the AGSA publication.

Reviewing such publications is rather fraught: the more that is available, the greater the opportunity to be better informed. In Aboriginal argot, ‘same, same, but different’; otherwise, lest we forget.

Comments powered by CComment