- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Modern travellers can hardly conceive the perils of the sea in the age of sail. Merchant seamen excepted, today’s average seafarer rides a massive cruise ship warned by radar to skirt round storms and stabilised against the rolling of all but the most powerful swells. The terrors of the deep do not extend far beyond poor maintenance, food poisoning, bad company, and illicit drugs administered by persons of interest to the police. Global positioning devices make navigation a breeze. Fifteen-year-old girls single-handedly circumnavigate the globe, and Antarctica is a fun destination for seniors.

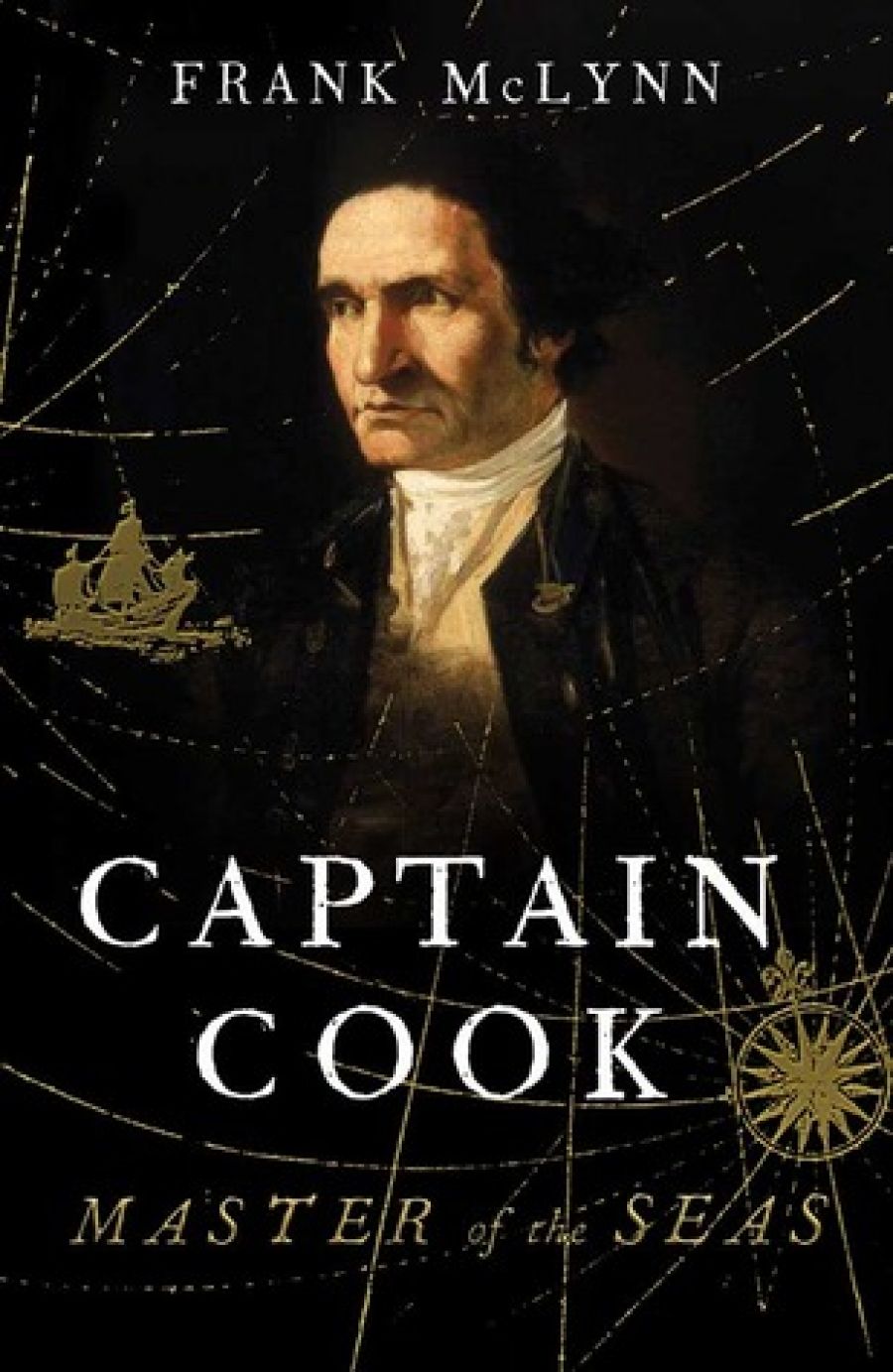

- Book 1 Title: Captain Cook

- Book 1 Subtitle: Master of the Seas

- Book 1 Biblio: Yale University Press, $45 hb, 510 pp

To conjure up how very different were Pacific voyages of the eighteenth century, imagine a five-day flight to Los Angeles during which the aircraft would incessantly pitch and roll. At any moment heavy weather might shoot the plane up two thousand metres, then cause it to plummet like a stone before steadying with a bone-jarring shudder. It would be little comfort to have the steward’s assurance that the captain had flown this route many times without coming near to hitting a mountain.

James Cook wins our admiration not just for piloting his ships through towering seas, typhoons, and ice fields, but for braving uncharted waters and coming back with accurate maps. That is why accounts of his voyages have enjoyed a wide readership over the last two-and-a-half centuries. A British explorer in West Africa once saved his skin by telling a cutthroat slave trader that he was on a mission like Captain Cook’s (the chief had a copy of Cook’s Voyages in his hut). Every decade or so a new biographer comes along to remind us of his greatness. The last was Vanessa Collingridge in Captain Cook: The Life, Death and Legacy of History’s Greatest Explorer (2002). Frank McLynn reiterates the message in a very handsome book. Justly renowned for meticulous production methods, Yale University Press has done the author proud. The cover is brilliant, there is not a typographical error to be found, the colour plates are marvellous, and the index is all that could be desired. Readers unfamiliar with Cook who want a day-by-day account of his voyages will find this an eye-opening introduction.

Scholars, however, will wonder why Yale took on the project. McLynn has nothing new to say about Cook or his ventures. He produces not a scrap of evidence that corrects or extends J.C. Beaglehole’s magisterial biography and extensively annotated editions of Cook’s journals. Indeed, most of McLynn’s notes reference Beaglehole’s work. It could hardly be otherwise, given the speed with which he works. In the past fifteen years, McLynn has produced biographies of C.G. Jung, Napoleon, Marcus Aurelius, Richard the Lionheart, and King John – not to mention a history of the Mexican Revolution, as well as Wagons West: The Epic Story of America’s Overland Trails (2002) and Heroes and Villains: Inside the Minds of the Greatest Warriors in History (2009). How does he do it? Simple. Take some standard reference works, adopt the point of view of your heroes, and proceed to give a chronological account of their lives. McLynn appears to have a fascination with explorers, for he has previously written on Henry Morton Stanley and Richard Burton. Why then was he not tempted to do some exploring of his own? Ask some new questions? Take a novel point of view? It is a mystery. What McLynn offers is not research, but attitude. Captain Cook was a great man whose opinions on all people and subjects were correct, though he lost the plot a bit on his final voyage.

In order to build up Cook, McLynn thinks it necessary to run down Joseph Banks, whose presence on the first voyage is regarded as an annoyance. His wealth and social connections are prima facie evidence he was a snob. What business had a trained botanist aboard a ship whose proper business was charting the Pacific and making observations of the transit of Venus? When Banks insists on bringing the remarkable Tahitian seaman and linguist Tupaia on board the Endeavour, Cook is annoyed because he could ‘see through’ the man’s pretensions to importance. So McLynn is also annoyed. This leads him to miss altogether Tupaia’s significance as a witness to the capabilities of Polynesian seamanship. He was able to point out correctly the precise position of scores of islands, and to accurately plot the Endeavour’s progress by the stars almost all the way to Indonesia. He could make himself understood to the Maori in New Zealand and to any other speakers of Polynesian languages. But because he big-noted himself to the Maori, McLynn wishes him gone. Banks also comes in for more scornful comment after the epic voyage simply because society treated him like a rock star, not immediately recognising Cook as the greater man. When Banks fails to win Admiralty support for inclusion in Cook’s second Pacific voyage, McLynn exults, for he was a ‘fantacist’, whose ‘loud-mouthed vociferations all over Europe’ must be deplored by men of sense.

Even worse treatment is accorded to the scientific complement on Cook’s next voyage: Johan Forster and his son George. They are ‘well summed up as “standard Teutonic Herr Doktor Professors”’. McLynn likes the joke so much he repeats it when describing ‘Herr Professor’s quarters’. Cook ‘could barely tolerate him; he had all Banks’s irritating quirks without his money and social status’. He was, in short, ‘a typical academic’ with ‘no street wisdom or even common sense’. The same goes for Anders Sparrman, a Swedish botanist whom the Forsters discovered in Cape Town and recruited to the voyage. No matter that he went on to write zoological and ethnographical accounts that continue to be consulted to this day. McLynn professes delight, along with his hero, when no scientists of any description are taken on the third and final voyage.

To most modern scholars, the greatest missed opportunity of Cook’s Pacific voyages was the failure to recognise the need for linguists who could engage with island peoples. Not until humble missionaries sat down in the 1820s to learn Polynesian languages and provide them with grammars did the West begin to get an idea of the complexity and accomplishments of these societies. Instead, eighteenth-century Europe ignorantly debated whether the South Sea savages were to be classed as noble or ignoble. McLynn enthusiastically enters the lists against Rousseau and others who celebrated life in the supposed state of nature. Cook (of course) correctly perceived the defects of savage society, unlike some of the officers who accompanied him. Lieutenant King, who was ‘inclined at first to be a bien pensant liberal’ only gradually ‘penetrated the savage reality of everyday life on the Friendly Isles’, and realised the necessity for Cook to punish incessant Polynesian thieving with floggings, shootings, and kidnappings.

Bien pensant (the new term of contempt for those formerly called ‘politically correct’) McLynn is not. While providing a veneer of rather antiquated anthropological commentary on Polynesian society, he expresses little sympathy or interest in the people. Most of us would find Omai of Tahiti a fascinating character. Taken to England by Tobias Furneaux, who commanded the Adventure, which accompanied Cook’s second voyage, Omai became the object of intense curiosity in London as the first visiting Polynesian. Because Cook disliked him and resented having him aboard his ship on his final Pacific voyage, McLynn ridicules him unmercifully. He is ‘the absurd Omai’ whose woeful attempts to speak proper English are hilarious. More character defects emerge when, back in Tahiti, ‘the crackpot scapegrace’ consorts with ‘flatterers, low-lives, vagabonds and wastrels’. How can this eighteenth-century invective possibly enlighten twenty-first century readers?

Things get much worse when McLynn gets onto sex, which he does a lot. Infuriated that Cook should ‘in later bien pensant criticism have been held responsible for spreading venereal disease around the Pacific’, when he actually tried to prevent it, the author explains over and over that no one could have stood between the sexually voracious Polynesian women and manly British tars. ‘Given human nature, this was like the legendary papal bull against the comet.’ In case you didn’t get it the first time, he later calls Cook’s prescriptions against venereal disease ‘like Canute ranged against the sea or the papal bull against the comet’. Words fail him, and fail him badly, when it comes to sexual congress. Men fight ‘over a dusky beauty’. ‘Tongan houris’ were ‘the most lascivious in all the islands’. Sailors are ‘crazed with desire for the voluptuous and curvaceous island girls’. Everyone gets ‘into the lubricious action’. There are ‘frenzied lubricious dalliances’, seamen ‘coupled frenziedly with the local girls’, caught up ‘in their pagan joy of copulation’.

Academic critics who raise their eyebrows at such views of first contact are denounced, but not engaged, by McLynn. ‘Some more howling and foaming-mouthed than others’, academics have seemed to ‘swim toward the dismembered hero like sharks, determined to finish him off’. With ‘certain scholars there is contempt and hatred of biography tout court’. He mentions no names, but we get the general idea. Today’s academics are the equivalent of Banks and the Forsters, pedants lacking in common sense and street smarts. And so we may be. The puzzle is that a book grounded on that premise should be published by one of the world’s great academic presses.

Comments powered by CComment