- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Cult of workplace

- Article Subtitle: A novel about our broken working lives

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

For earlier generations, joining a cult typically signified a rejection of mainstream values – careerism, property ownership, the nuclear family – in favour of spirituality and communal living. Ata time when a mortgage and stable employment are no longer assumed to be within reach of an average thirtysomething in Australia, the workplace arguably becomes a cult, with its own perplexing lingo, rigorous standards for membership, and redefinitions of family.

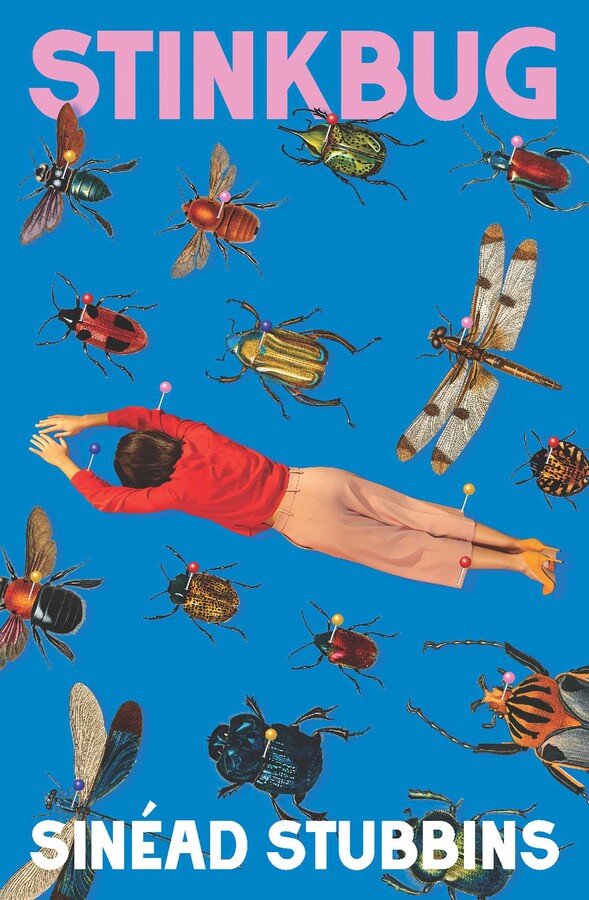

- Book 1 Title: Stinkbug

- Book 1 Biblio: Affirm Press, $34.99 pb, 304 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.readings.com.au/product/9781923135475/stinkbug--sinead-stubbins--2025--9781923135475#rac:jokjjzr6ly9m

Such is the thesis of Sinéad Stubbins’s corporate black comedy, Stinkbug, which follows the employees of Melbourne advertising agency Winked as they partake in a team-building retreat before a catastrophic restructure. ‘The Swedes are coming,’ a harried middle manager blurts out within the novel’s first pages, explaining why Winked’s CEO looks like he is ‘trying to electroshock his own brain’. Nöje, the Swedish firm taking over Winked, is a mysterious, cold-blooded interloper, inspiring nosebleeds and threatening mass redundancies ‘for aesthetics alone’.

The Swedish firm provides convenient cover for Edith, who masterminds the firing of her ex-boyfriend. The turfed-out Pete is as beloved at Winked as Edith is disliked, an imbalance that, while raising Edith’s social capital during the relationship (‘he softens you,’ says one colleague), causes her stock to plummet in its aftermath. Even as Edith fears for her future at Winked, she remains quietly, guiltily assured of her capacity for secrecy and backstabbing.

Edith is a gnarled character. Her unpopularity among her colleagues and dejection over the breakup, while positioning her as an underdog whom readers are inclined to root for, are complicated by her shiftiness. Deoes she actually experience a disadvantage? She has a ‘best work friend’, after all, in the assertive and charismatic Mo. She has the favour of testy British middle manager Danny. She is not relegated to administrative work like poor Eun-ji, the novel’s moral centre, who makes the mistake of coming back from maternity leave.

Although the Winked offices are a sausage fest, a male dominated environment in which Edith is expected to bring baked goods to morning teas, manage the men around her emotionally and logistically, and soften her demeanour so as not to appear threatening, she is skilled at playing the game. More importantly, she enjoys it. ‘Edith didn’t really care about the work she was doing,’ Stubbins clarifies early on. What Edith loves is the ‘ceremony of presenting an idea … in a 21.5 degree room that smelled of imported Japanese candles’, of anticipating clients’s needs, of ‘being the one to fix things’. To quote former Liberal politician Christopher Pyne, Edith is ‘a fixer’, and though her addiction to fixing is almost certainly maladaptive, it is an animating principle in the broken working world of which Winked is a microcosm.

It would be easy for Edith to fall into the trope of the messy, disaffected millennial woman who typically heads novels about late capitalist malaise. However, she is more active and less alienated than the protagonists in works such as The New Me (2019) by Halle Butler and Raven Leilani’s Luster (2020). Neither her sexuality nor her unhappy childhood is the main source of drama. Though Edith’s desires and motivations are often opaque to herself and the reader, her reactions appear as natural developments – or revelations.

Stinkbug is Stubbins’s first novel. It follows a comedic essay collection and an established career as a pop culture commentator and television writer. This background is evident in the novel’s many strengths. Stubbins has a knack for sketching minor and supporting characters through details of wardrobe, gesture, and turn of phrase. Take Bruno, ‘one of those bosses … who felt comfortable airing grievances to his subordinates as long as he ended his complaint with “but, anyway”’. Or Alice, who dresses like a member of Fleetwood Mac and refers to a South Asian office hunk as ‘Dev Patel’.

Wrangling a large cast of characters is an ambitious feat, one which is more readily achieved on the screen than the page. Although Winked’s advertising bros blur together, their idiosyncracies offer enough local colour to counterbalance moments of confusion (who is Keith again?). Moreover, some level of minor player dispensability seems fitting given the promise of a work retreat in the style of Battle Royale (2000).

If Edith is more than the sum of her parts, the same cannot always be said of the plot she is entangled within. I appreciated Stubbins’s choice not to engage in lengthy scene-setting, opting to intersperse swift action descriptions among dialogue. However, there are times when the logic of characters’ movements become lost amid the banter. The weighting of certain incidents, their very inclusion in the novel, at times seemed unjustified. Why, for instance, does Stubbins show Edith calling her mother in a moment of crisis, when the conversation does nothing to complicate or challenge the troubled relationship that has already been established?

Some of the more shocking aspects of the novel’s denouement risk eliciting shrugs rather than gasps. This may be because the ‘culty wellness’ narrative feels tired compared to Stubbins’s more nuanced exploration of the workplace and how spirituality, family, and ambition converge on this site. Where Stubbins lands in this exploration is open to interpretation. ‘Work is just work,’ declares Fredrich, a sage-like German graphic designer, when Edith asks whether he has succeeded in the team-building goal of making a best work friend. ‘You don’t have to love it. It won’t love you.’

These are wise words which come, notably, from an enigmatic European without a social media presence. Whether they are true for the likes of Edith is questionable. When being gainfully employed means sacrificing weekends, being a fun Friday drinks companion, and appeasing surrogate parents in management, work may in fact be everything – love included. As dystopian as this reality is, for a few misfits like Edith it may also be cathartic.

Comments powered by CComment