- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Music

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Paul was the walrus

- Article Subtitle: Why the Beatles endure

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The cover of the paperback version of Ian Leslie’s John and Paul comes with an extraordinary claim from British journalist Cailtin Moran celebrating ‘the first new Beatles story in decades’ (my emphasis). Really? Don’t we know everything about the band already? Do we need another book? Sure we do, after all, the Beatles are a monumental and serious subject for investigation. For instance, as Leslie recalls, the double A-sided single ‘Penny Lane’/ ‘Strawberry Fields’ was nominated by one critic as the greatest work of art of the last century. For some, this is an extraordinary claim, but then that is part of the joy of thinking about and being affected by the Beatles.

- Book 1 Title: John and Paul

- Book 1 Subtitle: A love story in songs

- Book 1 Biblio: Faber, $55 pb, 432 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.readings.com.au/product/9780571376124/john-and-paul--ian-leslie--2025--9780571376124#rac:jokjjzr6ly9m

Leslie is certainly invested in the affective nature of the Beatles. The book’s subtitle, A love story in songs, underlines his focus on the relationship of John Lennon and Paul McCartney, of how these songwriters spoke to that emotion in their work and indeed the kind of extraordinary responses they have elicited. Of course, the joy that many feel for the Beatles lies predominantly in the music, the life of the songs in the hands of other artists, and the way in which they have become a folk feature of everyday life, their words and melodies sung and played by young and old. Pleasures are manifest too in the ways and extent to which we – dissenters included – talk about the Beatles.

While not everyone has in them a book about the Beatles, most people have an opinion concerning their best song, their favourite member, identifying significant events as well as hearsay such as whether Paul really did die in a car accident in 1966. (He didn’t.) Opinions and perspectives are impassioned, whether original or rote, and are inevitably guided by the fact that from the very beginning the meaning of the Beatles was thoroughly mediated and mythologised, from within and without (‘here’s another clue for you all, the walrus was Paul’). This process continues, even as we get further from the eight glorious years in which they were active as recording artists.

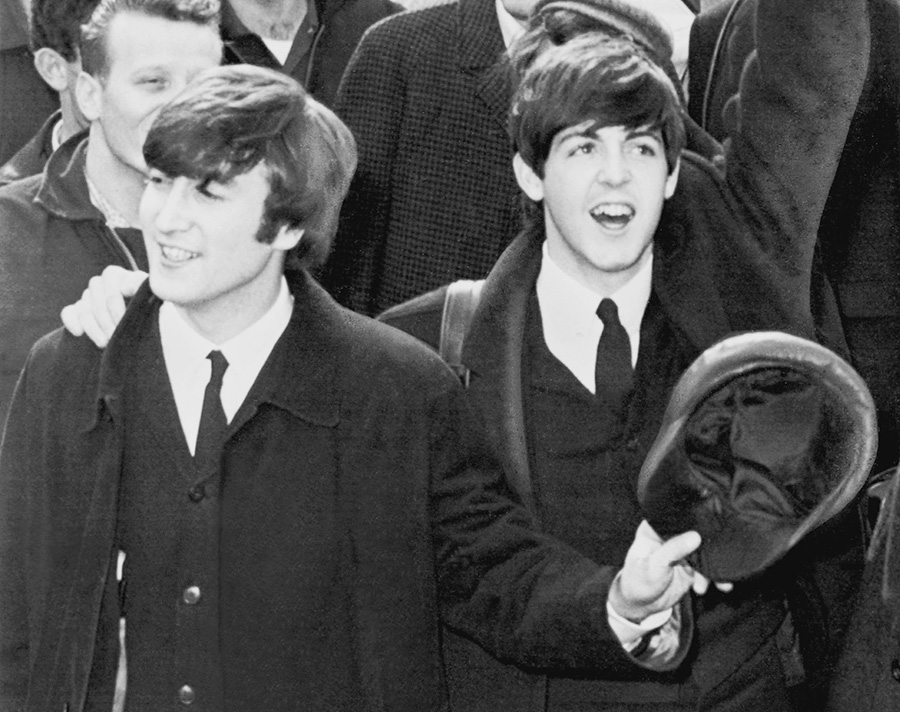

John Lennon and Paul McCartney at Kennedy Airport, 1964 (via Wikimedia Commons)

John Lennon and Paul McCartney at Kennedy Airport, 1964 (via Wikimedia Commons)

The authors of a great number of books about the Beatles are content to rehearse well-polished details and moments, providing the apocrypha accompanying the canonical recordings (188 originals and twenty-five covers released between 1962 and 1970). The challenge is to add new detail and perspective and assert why the Beatles still matter.

Kenneth Womack offered us Living The Beatles Legend: The untold story of Mal Evans (2023); in What They Heard (2021), Luke Meddings examined ‘how the Beatles, the Beach Boys and Bob Dylan listened to each other and changed music forever’. Popular music history and Beatles lore have been blighted by misogyny. An urgent corrective is Christine Feldman-Barrett’s A Women’s History of The Beatles (2022).

Moreover, there is a wealth of podcasts, weblogs, YouTube channels, and conventional films and TV series, equally well researched and often reflexive, regarding the Beatles. Peter Jackson’s bravura long-form documentary The Beatles: Get back (2021) displaced Michael Lindsay-Hogg’s miserable Let it Be (1970), its archival material suggesting different versions of the band’s end.

As Leslie observes, scenes from Jackson’s documentary portray four men who ‘slept on top of one another in freezing vans, who have seen one another fuck and wank and vomit and cry, who discovered drugs together, and who played to sixty thousand screaming fans’. As is well documented, professionally and personally, the band’s relationship was an intimate one.

With almost no original research, Leslie nonetheless makes creative use of an excellent, albeit limited, range of earlier work to tease out and explore this love story. Arguing that ‘we get Lennon and McCartney so wrong’, he suggests that we have a problem understanding deep friendships between men: ‘We’re thrown by a relationship that isn’t sexual but is romantic: a friendship that may have an erotic or physical component to it, but doesn’t involve sex.’ Maybe, but I suspect that this friendship may have been an aspect of the band’s appeal for all those young women, and often men, who screamed themselves hoarse when in live communion with the band.

A writer of several studies of human psychology, Leslie is adept at framing personal interactions. While sometimes limited in his writing on musical motifs, he constructs a valuable and lyrical thread in this moving and empathetic perspective. Inevitably perhaps, as he acknowledges, Leslie does a disservice to George and Ringo in exploring the qualities and depth of Lennon and McCartney’s mutual affection.

Leslie is sensitive to the emotional trauma experienced by Lennon and McCartney in the loss of their mothers during their teenage years – a loss which gave them a shared, if unaddressed, bond. The medium of song was how they communicated with the world, with each other, and indeed with their inner selves. As Leslie writes, ‘The songs they wrote and sang together were not “about” their feelings – they were their feelings, including those for each other.’ At worst this formulation presents lyrics as roman-à-clef (ah, so that’s what ‘I Lost My Little Girl’ is about!); at best it brings nuance to our understanding of the affective dimension of songs in their construction, performance, and consumption. He notes that Paul and John would often swap a song’s narrative voice in performance, managing melody in relation to the grain of their respective range: ‘A technical necessity resulted in the distinct and thrilling aesthetic effect of two men who share the same “I” – the same consciousness.’ For Leslie, this device expressed the camaraderie of the group, evoking ‘how two people can slip in and out of each other’s subjectivity: the way we internalize the voices of those we know and love’. In performance, in swapping lines and sharing the microphone, Lennon and McCartney enacted their love.

At the centre of Lennon and McCartney’s relationship, and this book, was their love of music and the mechanism of songs, as well as their fascination with words, chords, and musical discovery. This book shows why they were, and are, head and shoulders above so many of their contemporaries and those who followed. Leslie’s is a serious and imaginative book that befits its subject, demonstrating that the Beatles deserve the breadth and depth of attention, scrutiny, analysis, and continued reinterpretation that they engender. As some have observed, popular music may not be the vital force that it once was, but it appears that the Beatles will endure as testimony to its possibilities.

Comments powered by CComment