- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

‘Thank God I have done with him!’ – the words uttered by Dr Johnson’s publisher when he received the final proofs of the dictionary from its author – might well have been Peter Ryan’s own in 1988 when Manning Clark confessed that he had changed his mind about the character and career of Robert Menzies. No longer did Clark consider him an ‘imperialistic booby’. Melbourne University Press was about to publish the final volume of Clark’s History of Australia, and the book was printing as the author confessed that he no longer believed his own, uncomplimentary text. This, for Clark’s publisher, Peter Ryan, was ‘the last straw’ in their tumultuous publishing relationship of twenty-six years. He boycotted the launch, and five years later he let fly in the pages of Quadrant with a critical attack on the press’s most profitable author, his methodology, and his work.

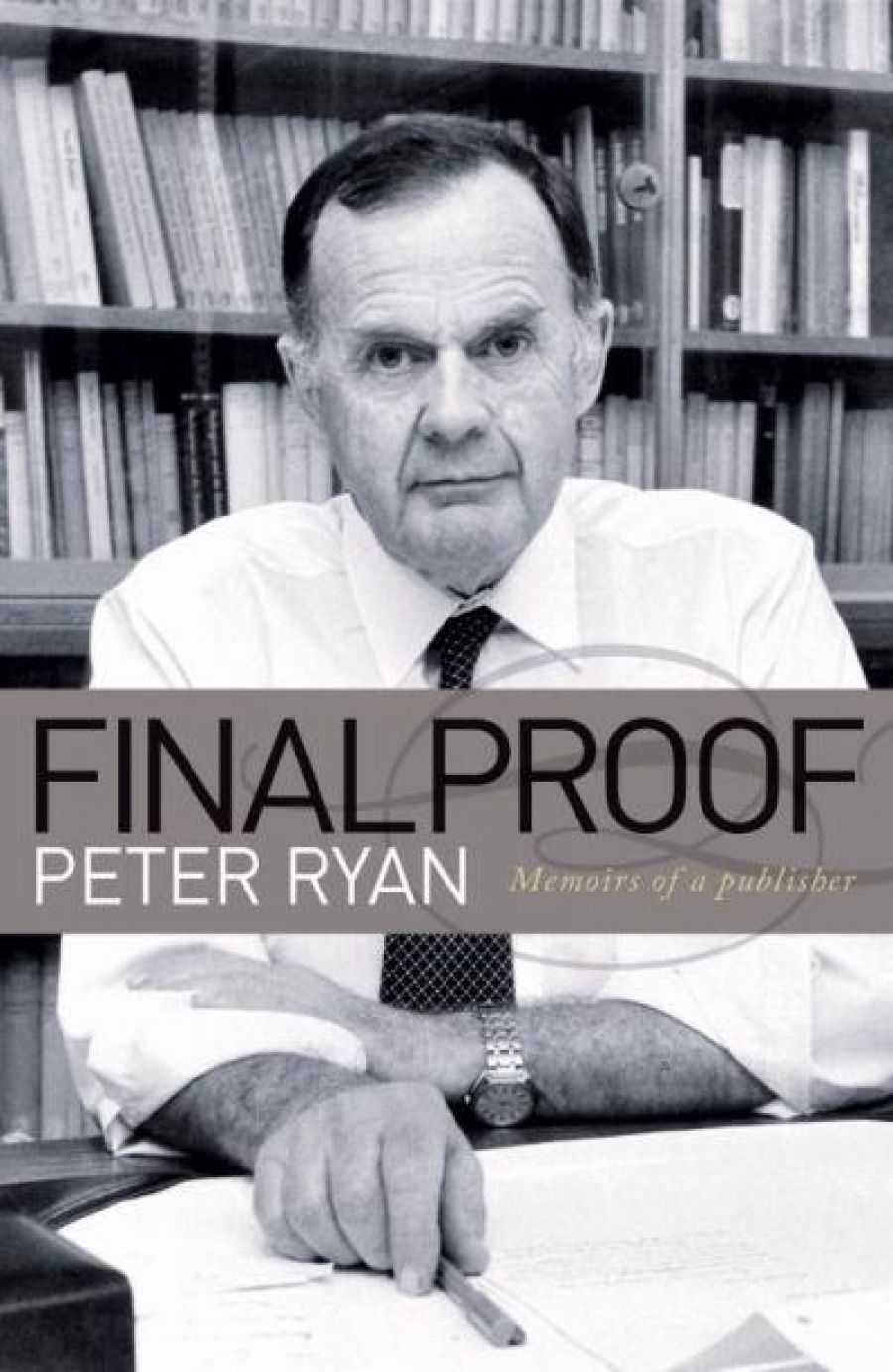

- Book 1 Title: Final Proof

- Book 1 Subtitle: Memoirs of a publisher

- Book 1 Biblio: Quadrant Books, $44.95 hb, 210 pp

Ryan tells us he was confident that his article was ‘polite’ and that ‘cogent evidence’ supported his assertions, but many did not agree – particularly some historians – and the article made headlines. Critics were ferocious and swift to respond; one choice description labelled Ryan ‘a pornographer of power’ (Professor Paul Bourke), and Russel Ward considered him ‘mad’. Ryan playfully described the years following his article as ‘My life as a leper’.

It is probably a coincidence that Peter Ryan’s Final Proof: Memoirs of a Publisher was launched six months before Mark McKenna’s biography of Manning Clark appeared in May 2011 under the Miegunyah imprint of Melbourne University Publishing, but given the uproar Ryan created with his Quadrant article in 1993, it is inevitable that his name will continue to be linked with Clark’s. He contributed to this nexus himself when his Lines of Fire: Manning Clark and Other Writings was published in 1997, even as he asks us to forget about the Lenin lookalike and his ‘long and windy’ history. (The publisher in him must have gained the upper hand here – commercial advantage over the author’s finer feelings.) They had known each other for fifty years, since Ryan attended Clark’s lectures as an undergraduate after World War II. McKenna’s book partially exposes some of the frustrations suffered by Ryan over twenty-six years, as he maintained that delicate balance between producing as scholarly a work as possible from a profitable author whom he considered unsound, and not killing the goose that continued to lay MUP’s golden eggs. Any publisher will recognise the balancing act. The eruption that occurred two years after Clark’s death, and that blew to kingdom come the traditional confidential relationship between publisher and author, had been seething under a thinning crust of tolerance for over thirty years.

Many will know Ryan as the author of Fear Drive My Feet (1959), his autobiographical account of wartime Intelligence work behind the Japanese lines in New Guinea (for which he won the Military Medal); his reviews and articles have been published widely; and since 1993 he has been a regular contributor to Quadrant, now the voice of the literary right under its editor Keith Windschuttle, a leading protagonist in the ‘history wars’.

What were Ryan’s qualifications in 1962 for the new role of director for Australia’s oldest university press? He prided himself on his ability ‘to do an elegant lunch’ – expected, almost without exception, by authors – and ‘passionately shared with Gibbon “the early and invincible love of reading”’. It was, he says, ‘the luckiest break of my working life’.

He skates lightly across his time as a left-wing ex-serviceman undergraduate and friend of Creighton Burns, then an academic at the university but later to be editor of The Age,whom Ryan had to thank for his appointment as a suitable successor to Gwyn James. Not everyone approved of the new director. His public relations experience, plus a few forays into the publication of comics and racing form guides, led to John La Nauze, a member of the university’s Press Board, threatening to take his manuscript on Alfred Deakin to Cambridge University Press if they persisted in employing a ‘crass commercial type from downtown’. Too late: the university had chosen and the appointment had been made. La Nauze calmed down and that redoubtable editor Barbara Ramsden apparently breathed a sigh of relief at the prospect of a new boss. Ryan was even more relieved that Ramsden would continue to oversee the editorial department, for he had only a hazy idea of how to begin building a list, although he soon conquered the challenge of running a mixed business that comprised a printery, a campus bookshop haemorrhaging turnover through persistent thievery by students (plus an academic or three), a post office, and various other commercial opportunities.

On his admission, Ryan took MUP from near-bankruptcy to comfortable profits and a healthy reserve during his twenty-six-year reign, and his publishing skills were as well developed as his fiscal competence: the list is a roll-call of distinguished Australians: Geoffrey Blainey, Robin Boyd, Bill Gammage, Keith Hancock, Paul Hasluck, Alec Hope, Ken Inglis, Geoffrey Serle, Kenneth Slessor, Gavin Souter, to name but a few. There were bestsellers – not least Manning Clark – and the first twelve volumes of the Australian Dictionary of Biography appeared under his watch and imprint; he was the general editor of the Encyclopaedia of New Guinea.

He also induced the staid old lady of MUP to pick up her skirts and enjoy the pleasures of promotion. Clark’s was the first MUP campaign ever, with a rip-roaring launch well fuelled by alcohol and ‘the three most obstreperous drunks of Melbourne’s literary left’. What the formidable Ramsden thought of this romp is not recorded, but her liking for whisky is, so I suppose she was happy to participate. The latter’s influence on editing, editors, and authors was profound, capable as she was of reducing strong men and women to speechlessness with what Ryan is pleased to call a ‘conversational stun-gun’ that invited no riposte. I have never met Peter Ryan, but during the early years of my much lowlier publishing career, I was very aware of the legendary Barbara Ramsden, and Ryan’s admiring reminiscences are a respectful but highly entertaining series of snapshots of daily publishing life in another era.

As, indeed, is the entire book. But for the annual losses from shoplifting, they would have been halcyon days. His urbane and measured style was forged under the critical eye of one Gordon Connell, who taught him English and History at Malvern Grammar and reappeared forty years later, manuscript in hand, as a prospective author. (In his report, Ryan deducted half a mark for ‘neatness’.)

Many old friends with whom I too enjoyed publishing relationships enter and exit the memoirs: rotund Colonel Alex Shepherd, who, like Ryan, operated behind enemy lines, but in Greece rather than New Guinea; Dr Jim Willis, with his beautiful handwritten manuscripts; and author of The Land Boomers, Michael Cannon. The last-named was Ryan’s choice as his successor, only to be pipped at the post by John Iremonger. Ryan interpreted this act by his Press Board as a betrayal and was so incensed that he ‘parcelled up’ the rare copy of Samuel Johnson’s Journal to the New Hebrides, which had accompanied an illuminated address as his retirement present, and returned it to the university with a curt letter. Apart from the titles on Ryan’s bookshelves, it seems the only souvenirs from those publishing days are his memories and Barbara Ramsden’s pair of ‘stout and serviceable desk scissors’, which ‘trimmed the proofs and, in certain cases, the authorial extravagances of some of Australia’s greatest books’.

Comments powered by CComment