- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Bookended by death

- Article Subtitle: Poetry which respects history

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The selected work of a long-lived poet presents the reviewer with so much to consume. A long life and career give a poet plenty of time to make their way through different styles and themes and, perhaps most importantly, to witness moments in history and shifts in culture. In this case, we have a career spanning fifty-something years and a life that ended in 2021.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Sam Ryan reviews ‘Greatest Hits: Poems 1968-2021’ by Tim Thorne

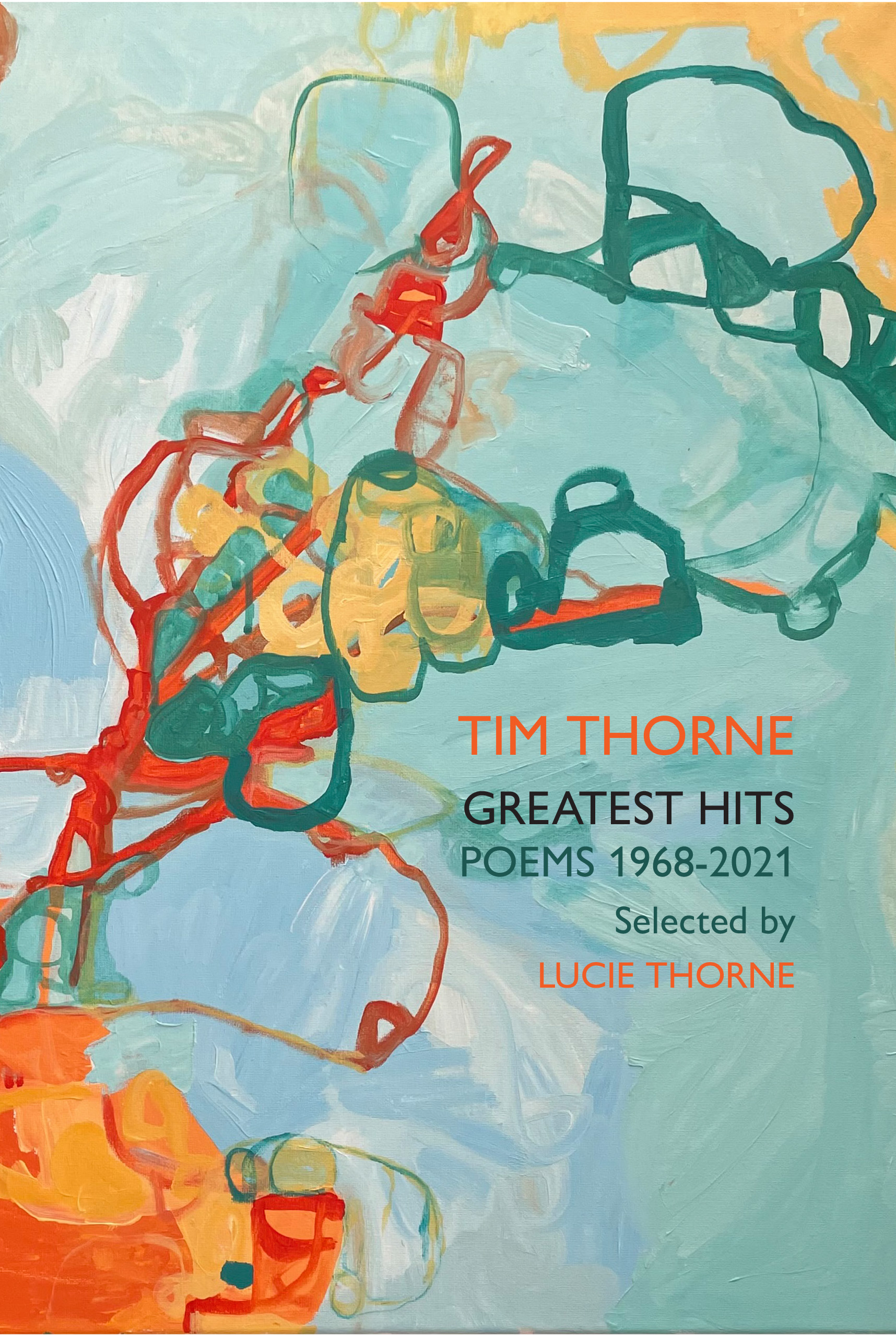

- Book 1 Title: Greatest Hits

- Book 1 Subtitle: Poems 1968-2021

- Book 1 Biblio: Puncher & Wattmann, $32.95 pb, 233 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.readings.com.au/product/9781923099296/greatest-hits--tim-thorne--2024--9781923099296#rac:jokjjzr6ly9m

Noting the poet’s death may seem like a morbid way to begin a review, but this selection of Tim Thorne’s poetry is bookended with death. It begins with the poet’s auto-obituary and ends with ‘Epitaph’, which contrast a solemn mourning with an almost glib acceptance. The obituary is a standard one, detailing the poet’s life and achievements. The final poem is almost flippant and nihilistic, ‘I did not pass. I failed / to stay alive. There is no other side.’ To start and finish with these references to the poet’s death gives the collection a sense of monumentality. What lies between these two literary gravestones is a selection of the poet’s works from his sixteen collections, with a few unpublished poems at the end.

Pop culture and high-minded references mix, earning the ‘greatest hits’ portion of the book’s title. In ‘Are We There Yet?’, Thorne starts with Corey Worthington, that yellow sunglassed youth, and Narre Warren and alcopops, and then moves to Sigmund Freud, and Beijing in 1989, using these eclectic references to describe suburban mundanity and a kind of literary wanderlust. A few pages later, in ‘Clancy of the Cultural Studies Department’, Thorne writes after Banjo Paterson:

In my academic fancy non-visions come of Clancy

no longer prowling libraries or the student union bar.

Vanished thanks to Derrida: not even dead and buried a

worse fate could not have been his had he been hit by a car.

This tongue-in-cheek nod to, or mocking of, the academy written in that famous metre might be typical of Thorne. He is comfortable in his intellectualism, with little to prove. He doesn’t feel the need to pay much reverence to poetry’s theoreticians, though he is clearly aware of their work.

History, and the events that shape it, are paid their due respect. The poems in the series ‘Fukushima Suite’ explore the various stages of the nuclear disaster’s effects, ‘the amniotic ocean in slow spin / delivers change, brings Hello Kitty catfish’. In ‘Piraeus’, he memorialises Alexandros Grigoropoulos, who was killed by police during the 2008 anti-austerity protests in Greece. In ‘Chile, September 1973’, he writes about Victor Jara, a guitarist tortured and executed during Pinochet’s coup,

We know better. We know that your guitar

held more humanity than all Kissinger’s thugs,

and that, around the world, it still

accompanies a growing chorus of voices.

Thorne is attentive to history’s impact on art and its denizens, and their obligation to tell its stories. The nine-poem ‘Mesopotamian Suite’ is a good example of this, with Thorne reflecting on the Second Gulf War, mixing then-current politics and critiques of Western imperialism with references to the ancient culture that occupied the land where so many wars have been fought.

Thorne is appropriately intertextual for a poet whose career spanned so many years in Australian literary circles. Banjo Paterson is referenced, and John Forbes, Gwen Harwood, Shelton Lea, and more contemporary poets like Kent MacCarter, all make an appearance. Ern Malley – Australia’s most famous poet, depending on whom you ask – even gets a line.

The previously unpublished poems, ‘The Golden Mile’, ‘Chemo’ and ‘Epitaph’ – presumably written towards the end of the poet’s life – adopt an appropriately more sombre tone. Of the three, ‘Chemo’ is my favourite. In typical fashion, Thorne mixes history (‘Cancer is not the Ottoman empire’), sarcastic irony (‘six pairs of steel-caps marched in / to demonstrate bedside manner’), and a reference to a great Australian poet, (‘named after a Forbes collection, / ‘The Stunned Mullet’), to chronicle his time in chemotherapy. He devotes the final stanza to Tasmanian devils:

Then back home where the cancers are on the devils

and metastase across the landscape as plantations

of greed and nitens: Tasmania! I would weep for you

but the cytotoxins have turned my tears to poison.

Thorne was a lifelong Tasmanian and there’s a lot of Tasmania in this collection. ‘Waldheim’ references the Waldheim Cabin, a colonial-chic shelter in the state’s centre, which is part of a ‘Siegfried Line’ that stretches across the landscape ‘to keep the currawongs and ring-tails in Prussian discipline’. As with many Tasmanian poets, the island and its history are especially important to Thorne. In ‘Love on a Brick’, he writes, ‘“Love” impressed on a convict brick / instead of an arrow shows that someone soared / out of Van Diemens Land’s [sic] cold mud.’

Working with Tasmania’s unique brand of parochialism was a theme throughout Thorne’s life: many of the island’s poets understand that that parochialism is to be embraced, shunned, and, if necessary, denied. A Tasmanian poet needs to be both proud and ashamed of their isolation. Thorne shows a healthy mix of the two.

The state seems to punch above its weight in the business of producing poets, and Thorne was one of our best. His daughter, Lucie Thorne, has done us all a service in her curation of this collection.

Comments powered by CComment