- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Fossil and Lamb

- Article Subtitle: Poetry of the provisional

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Barry Hill has written thirteen collections of poetry, including Eagerly We Burn: Selected poems 1980-2018 (Shearsman, 2019). These volumes demonstrate his interest in the natural world, Australian history, White Australia’s relationships to Indigenous and Asian cultures, and cross-cultural experiences more generally. His poetry explores politics, art and ekphrasis, literature, autobiography, and spiritual issues, including, persistently, Mahayana Buddhism and its teachings about ‘emptiness’.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Paul Hetherington reviews ‘Lamb’ by Barry Hill

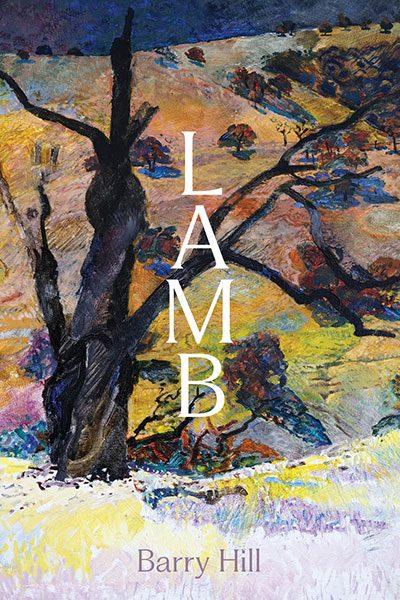

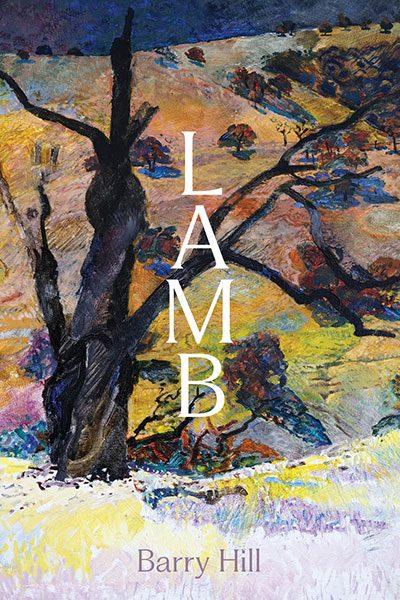

- Book 1 Title: Lamb

- Book 1 Biblio: re.press, $30 pb, 199 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.readings.com.au/product/9780648728276/lamb--barry-hill--2024--9780648728276#rac:jokjjzr6ly9m

At nearly 200 pages, Hill’s latest book, Lamb, is relatively long. It is more discursive and colloquial than much of his earlier work, although consistent with his longstanding interest in constructing poetic sequences. Indeed, it is a kind of diary in verse covering a moderately short period when, as he states in the volume’s Preface, he turned eighty and in ‘the same year fate and good fortune injected me with a sense of rejuvenation in the form of my first grandchild, a little girl called June, aka … Lamb’.

Lamb is both a ‘real’ figure in this book – foetus, infant, toddler – and also as a motif or symbol representing a transformative renewal and hope: ‘I was so overcome by the sudden flare / of light in the heart, its gash of slow vanishing fire / like a star’s message, that I am still holding / a vedic breath with the image of it’ (‘Great Mother Ultra-sound’).

More generally, this volume extends Hill’s interest, present throughout his oeuvre, in presenting his responses to environments he encounters and situations he witnesses, along with the events and occasional disruptions of his domestic life. This self-reflexivity includes the use of an alter-ego named Fossil, who is a somewhat opaque and ultimately elusive figure.

Overall, the self-reflexivity is mostly deftly handled, although occasionally there are moments of self-consciousness that disrupt the poetry’s flow. Perhaps these moments of disjuncture are deliberate as Hill attempts to make connections, or to reveal the dislocations, between ideas of nascency and self-perception, warfare and its cruelties, openness and cynicism, apartness and togetherness, the quotidian and the abstract, self and emptiness, and poetry and the spiritual.

Conduits into understanding these juxtapositions are provided by Hill’s extensive use of quotations from two primary texts, many as epigraphs to his poems. The first is David Hinton’s translation of a selection of the work of the eminent Chinese Tang Dynasty poet Tu Fu (712-770). Tu Fu’s often autobiographical poetry unites key Confucian, Buddhist, and Daoist ideas; he lived through and documented aspects of the catastrophic Chinese civil war known as the An Lushan rebellion (755-763). Hill identifies with him, writing: ‘again I felt like Tu Fu. / Between rebel uprisings, Tu Fu hunkered down’ (‘Amble-Awe’). The second text he mines for numerous quotations is Norman Waddell’s translation of the famous and sometimes acerbic Commentary on the Heart Sutra by the Japanese painter, calligrapher, and Zen Master Hakuin Zenji (1686-1769).

Almost inevitably, the various subjects Hill addresses do not fully cohere as he highlights the contradictory and irreconcilable nature of different aspects of human perception and experience, even while pondering forms of synthesis and resolution. His Preface states that Lamb was partly prompted by ‘the disgraceful exit from Kabul by the American armed forces, when they took the money and ran … about the time the Russians invaded Ukraine’. Gaza is also mentioned. The book more than once refers to the continuous nature of warfare and its grotesqueries: ‘In the other war / all seek to survive the slaughterhouse. / Starving children die in memories / of rubble. No way out. / We are what we are // riddled in fretful peace’ (‘Dead Man Peeping’). Hill’s frequent allusions to and remarks about war are mostly passing comments on the destructiveness of human behaviour, or particular examples of crisis or harm, and they have a cumulative and salutary effect. They are also laterally informed by the deep consideration of, and immersion in, the human predilection for destructiveness we find in Tu Fu’s work, delivered via Hill’s quotations.

The most compelling aspect of this book is its sometimes idiosyncratic and surprising meditations on and around the birth and early life of Lamb, and the poet’s tender association of her with his reflections on mortality and frailty. In this light, his quizzical and eddying considerations of notions of self and self-understanding, along with ideas of presence and emptiness, take on a moving resonance and gravitas:

Fossil nurses a picture of a toddler

losing her way in the nursery. She is such a lamb.

All she has to go by is her own gentlenessand Fossil would follow her anywhere

during this war, or the next, if it comes to that.(‘No Title Today’)

Such reflections gain additional weight because the poet does not shy away from registering a powerful sense of human imperfectibility, including his own.

It is in this context that Hill’s Buddhist preoccupations are animated as a way of informing his sometimes provisional understandings of himself as a poet and person. Indeed, as this work proceeds, its sense of provisionality is revealed as one of its major preoccupations. The collection returns repeatedly to the contrasts and contradictions between what W.B. Yeats called ‘bodily decrepitude’, new life, and the striving to create art and make sense of a troubling world.

In pursuing these ideas, Hill asserts the importance of human connection, however problematic it may be, along with thoughtfulness and care as a counterpoint to the grinding brutalities and arbitrariness of war. In doing so, he invites the reader to travel with him into personal anecdote, extended ruminations, and moments of reminiscence in order to move into the realm of a broader philosophical questioning.

Comments powered by CComment