- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Music

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Bong bong bong

- Article Subtitle: Genius rarely looms larger

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

You can imagine the question popping up on one of those television quiz shows. What connects Miles Davis, John Coltrane, and Bill Evans? Anyone with a rudimentary knowledge of jazz would have hand on buzzer in a flash. Answer: Kind of Blue. There is an altogether darker, and equally correct, answer: heroin.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Des Cowley reviews ‘3 Shades of Blue: Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Bill Evans and the lost empire of cool’ by James Kaplan

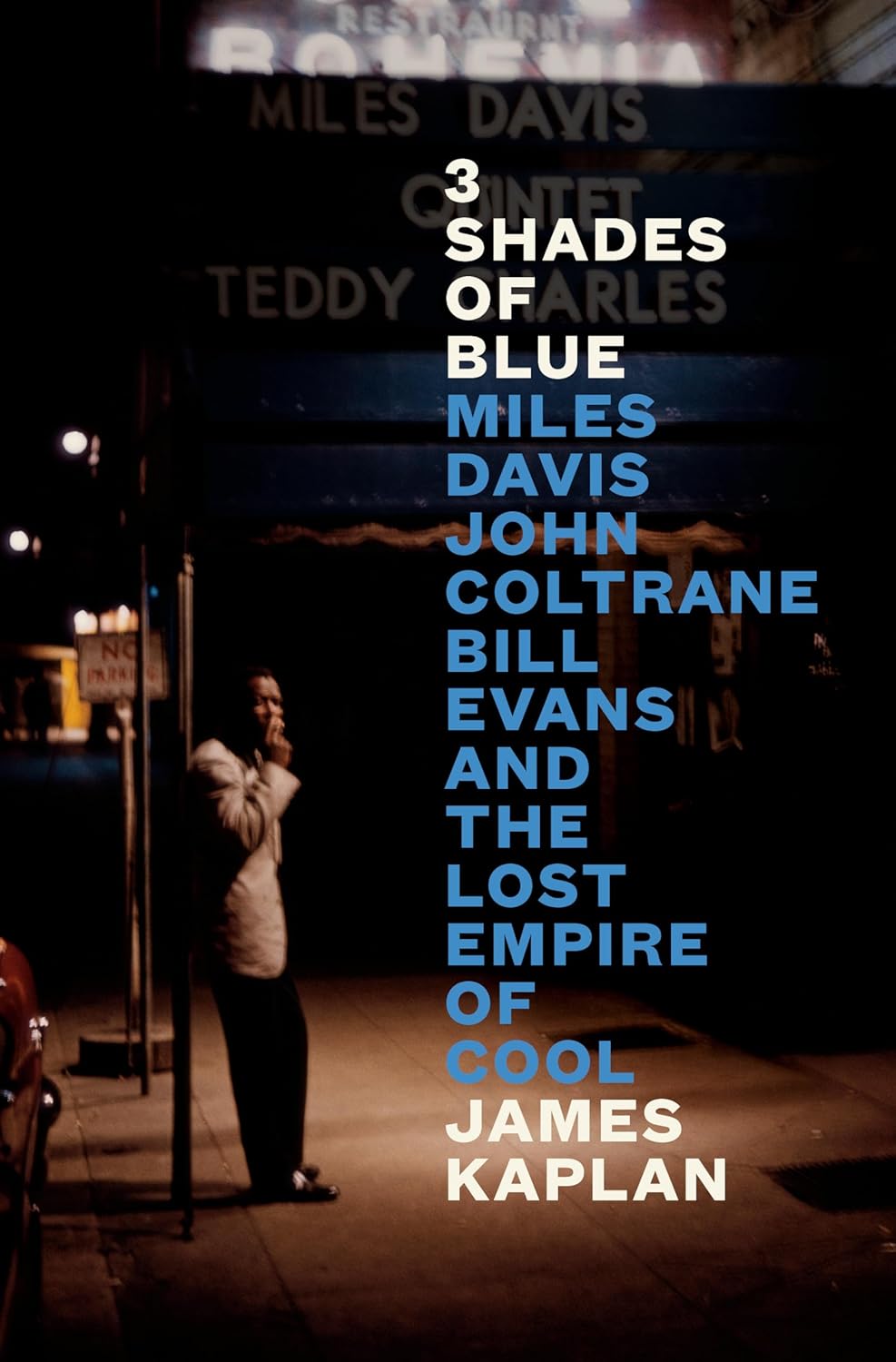

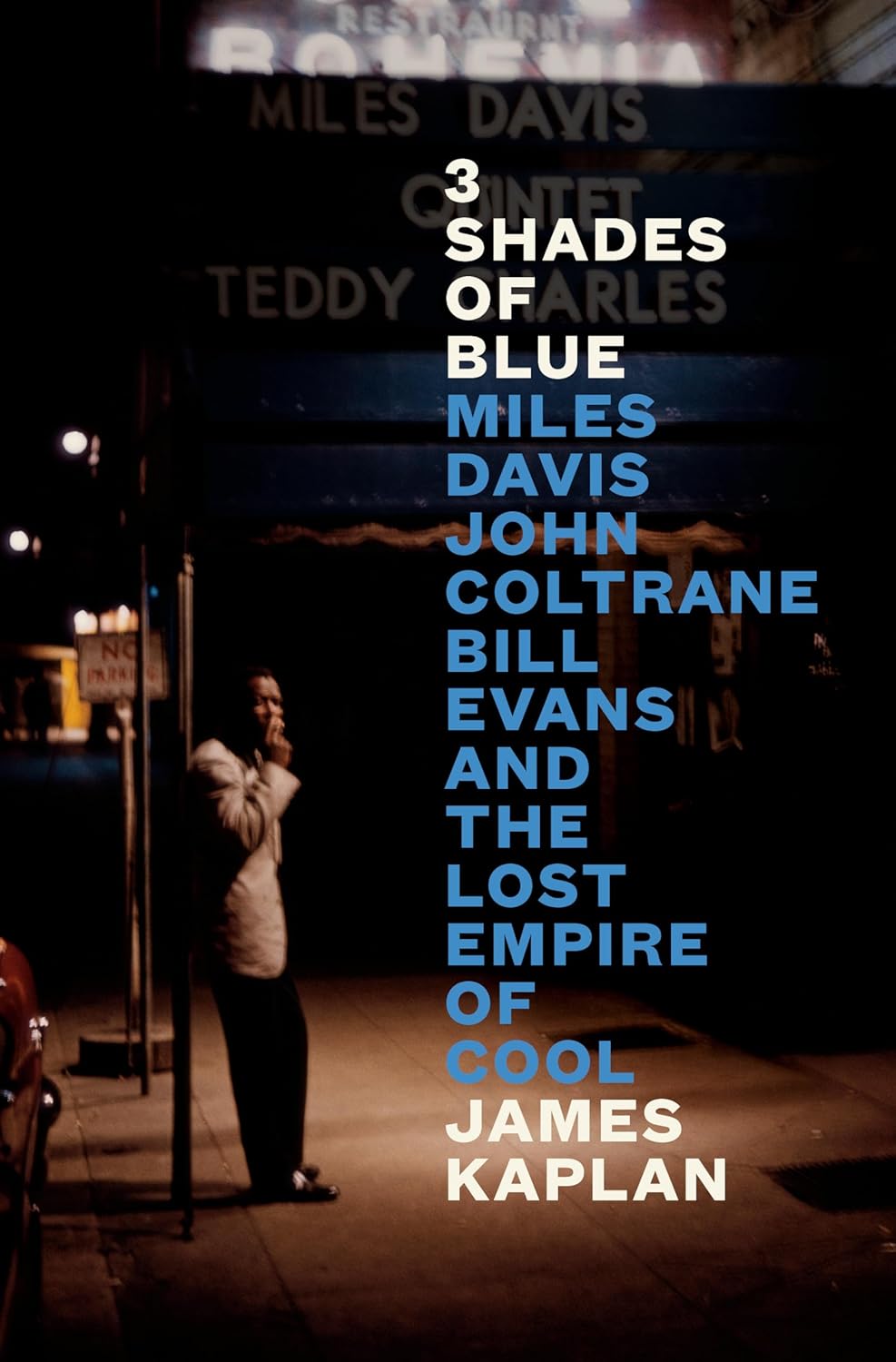

- Book 1 Title: 3 Shades of Blue

- Book 1 Subtitle: Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Bill Evans and the lost empire of cool

- Book 1 Biblio: Canongate Books, $49.99 hb, 484 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.readings.com.au/product/9781805302001/3-shades-of-blue--james-kaplan--2024--9781805302001#rac:jokjjzr6ly9m

On paper, it no doubt looked like a good idea. Three revered musicians, each a towering figure in jazz, who came together in Columbia Records’ Thirtieth Street studio on 2 March 1959 (there was a second session on 22 April) to create what is arguably the greatest jazz album of all time. The fact that all but one of its tracks, aside from a few false starts, were recorded in single takes, mostly cobbled from Davis’s rough sketches brought along to the sessions, remains stupefying. Genius rarely looms larger. The sextet that recorded Kind of Blue never performed together again, and few pieces from the album were ever performed live. In Kaplan’s estimation, the three key musicians – Davis, Coltrane, and Evans – ‘came together like a chance collision of particles in deep space, produced a brilliant flash of light, and then went their own separate ways to jazz immortality’.

Given the time that has elapsed – more than sixty years – and the fact that few are left to tell the story, Kaplan by necessity leans heavily on those authors who have preceded him: Miles Davis’s The Autobiography (co-authored with Quincy Troupe, 1989), Ashley Kahn’s Kind of Blue: The making of the Miles Davis masterpiece (2000), John Szwed’s hefty biography on Miles Davis, So What (2002), Peter Pettinger’s Bill Evans: How my heart sings (1998), and countless others. While this reliance on secondary sources comes with obvious pitfalls, Kaplan has supplemented his account with a small selection of firsthand interviews, including with Wallace Roney, Chick Corea, and Jack DeJohnette.

Kaplan makes patently clear that saxophonist Charlie Parker was key to Davis’s early career (and, to a lesser extent, Coltrane’s). Parker’s fluency on alto, combined with his innovative approach, served to upend jazz’s popularity as dance music, ushering in the modern. To an eighteen-year-old Davis, Parker’s and Dizzy Gillespie’s intricate, high-speed tempos – designated Bebop – represented the future.

Unable to play as high or fast as Gillespie, Davis instead converted his shortcomings into strengths, playing in the middle register, and developing a drop-dead gorgeous tone. By 1945, he had assumed the trumpet chair in Parker’s band, going on to record a series of classic sides for the Savoy and Dial labels that represent high-water marks in jazz history. Few careers get off to such auspicious starts.

John Coltrane, Cannoball Adderley, Miles Davis, and Bill Evans, 1958 (Album/Alamy)

John Coltrane, Cannoball Adderley, Miles Davis, and Bill Evans, 1958 (Album/Alamy)

The fact that Parker could play with such dexterity while high on drugs provided unfortunate encouragement to others. Within a few brief years, a new generation of innovators, inspired by Parker’s example, were battling their own demons: Davis, Coltrane, Sonny Rollins, Jackie McLean. It kept Davis in the wilderness for the better part of a decade, incapable of holding together a steady band, even as he recorded prolifically. It would not be until he kicked the habit, around 1954 (stories vary), and put together his first great quintet, with John Coltrane, that things fell into place. Signed to Columbia Records in 1955, he produced a series of brilliant albums – especially those with composer and arranger Gil Evans – that laid the groundwork for Kind of Blue.

Kaplan is judicious in cherry-picking those stories that best track Davis’s and Coltrane’s convoluted trajectory in the lead-up to the 1959 recording. If anyone gets short shrift, it is pianist Bill Evans, who does not appear in Kaplan’s account until near the midway point. Yet Evans’s presence was crucial to Kind of Blue. The pianist, schooled in George Russell’s musical theories, was ripe to translate Davis’s musical vision, which preferenced modes over chords, to the point of assuming a co-composer role (uncredited at the time).

If Kaplan handles his early material adroitly, his chapters on the recording of Kind of Blue come across as anti-climactic. While he covers the bases – who, what, when – he is hard pressed to reveal the mystery. From thereon, his book scatters in all sorts of directions as he strives to chart the largely separate careers of these artists, who between them expanded the vocabulary of jazz. Coltrane went on to record A Love Supreme in 1964 – an album that rivals Kind of Blue as one of the bestselling albums in jazz history. Davis kick-started fusion or jazz rock (call it what you will) with Bitches Brew (1970); while Evans reinvented the piano trio with his 1961 Village Vanguard recordings, featuring bassist Scott LaFaro and drummer Paul Motion. There is a lot to unpack, arguably too much, and Kaplan is forced to skate over much of it, giving little more than a passing nod to Davis’s ground-breaking recording In a Silent Way (1969) or Coltrane’s watershed album Ascension (1966).

Where Kaplan excels is in his capacity to get inside this music. When he writes ‘At several junctures, for a few breathless seconds, the rhythm section seems to stand in place: as [Horace] Silver and [Jimmy] Heath play a repeated three-note figure – bong bong bong, bong bong bong – Miles blows along on top, fast but with entrancing gentleness’, he provides new entry points into this music.

While Kaplan’s suggestion of a ‘lost empire of cool’ harbours romantic overtones, the reality was far grittier. Charlie Parker was dead by 1955, aged just thirty-four years (the attendant doctor guessed his age was fifty-three years). Coltrane, clean after his early drug habit, burned like a supernova before his premature death in 1967, just shy of forty-one years. Miles would replace heroin with a heady cocktail of cocaine, prescription pills, and alcohol, suffering bouts of ill health from the 1960s onwards. He limped along, invariably producing great music, until 1991, succumbing at sixty-five.

It is the sad tale of Bill Evans death that Kaplan dwells upon in his final chapters. Evans may have looked more like an accountant than a jazz musician, but the heroin habit he picked up in the 1950s proved a lifelong affair. His later years make for harrowing reading, the drudgery of lonely hotels and one-night stands (though the quality of his music rarely suffered), essential to fund his habit, even as he functioned on ‘an eighth of a liver’. Evans’s final girlfriend, Laurie Verchomin, later described ‘her first sight of Evans’s thin legs, cratered and scarred by two decades of drug injections, [as] “something like the surface of the moon …”’.

Kaplan’s engaging narrative will absorb readers wanting to know more about his subjects. If he has failed to sufficiently plumb the depths of these lives, it is because his chosen form – the ‘group biography’ – proves too much of an ask when faced with three of the greatest jazz artists of the twentieth century.

Comments powered by CComment