- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Photography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Three worlds

- Article Subtitle: A new biography of Max Dupain

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Max Dupain’s photographs are well known to Australian audiences. The monumentally cast upper body of his friend Harold Savage, prostrate on the sand is, as Helen Ennis notes in her new biography of Dupain, the ‘most reproduced photograph in Australian history’. The Sunbaker’s ubiquity has seen it configured, well beyond Dupain’s intention, as ‘an ideal of Australian masculinity’. More recently, it is a photograph that has been restaged by artists as a form of creative and cultural critique.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Elisa deCourcy reviews ‘Max Dupain: A portrait’ by Helen Ennis

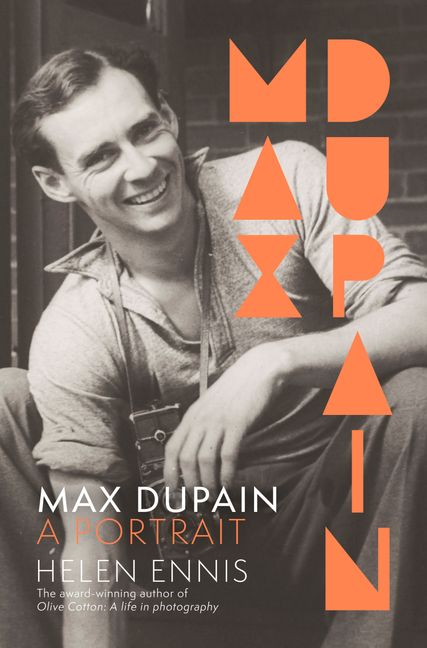

- Book 1 Title: Max Dupain

- Book 1 Subtitle: A portrait

- Book 1 Biblio: Fourth Estate, $55 hb, 532 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.readings.com.au/product/9781460764800/max-dupain--helen-ennis--2024--9781460764800#rac:jokjjzr6ly9m

During his career, Dupain received substantial commercial and artistic patronage. He worked for architectural luminaries, such as Harry Seidler, photographing Australian modernist design. Dupain was also commissioned by companies like CSR to document Australian industry. Alongside assignments such as these, he ran a largely successful portrait studio and maintained a robust art practice in Warrane/Sydney from 1934 until 1991.

Dupain’s images were collected as the bedrock of a contemporary Australian photographic practice when galleries and libraries around the country established dedicated photography curatorial departments from the late 1960s and 1970s. This would also be the case at the National Gallery of Australia, where, in an apt synergy, Dupain was additionally called upon to photograph the construction of the building and within whose inaugural photography department Ennis was employed from 1981 to 1992. Dupain is among the first Australian-born photographers to have his work considered as art worthy of collection by state and national galleries. The first dedicated survey exhibition of his photographs was mounted at the Art Gallery of New South Wales in 1980, curated by Gael Newton. By this stage, Dupain’s images were already familiar to Australian audiences. His photographs had been reproduced in leading twentieth-century periodicals, including Sydney Ure Smith’s The Home and in artist and coffee table books authored and produced by Dupain and others.

Dupain’s work has not evaded attention, and this is precisely Ennis’s point: any knowledge of Dupain himself has long been suffocated beneath his photographs.

The key to Max Dupain: A portrait lies in the subtitle. In seven parts and across sixty-eight concise chapters, Ennis delivers an excavation of the artist as a man. This is an approach signalled first and foremost by the opening illustration which is not by Dupain. It is a portrait of Dupain awkwardly posed during 1984 in his Artarmon studio on Cammeraygal Country for architectural photographer John Gollings. The biography’s penultimate illustration is also a portrait of Dupain, shot in 1991 by the sensitive photographer William Yang, in the same studio. These portraits bookend a literary portrait spanning Dupain’s life. Ennis brings Dupain out from behind his camera, contextualising his uneasy figure in the latticework of his personal relationships, professional associations and artistic influences (what he called his ‘three worlds’).

This is not to say that Dupain’s own photographs do not have their place within this story. The structure of Max Dupain: A portrait mirrors Ennis’s award-winning biography Olive Cotton: A life in photography (2019). Ennis introduces individual photographs interspersed as micro-chapters in the text. This slows down the narration, providing visual reference to the photographic work taking place alongside the life laid bare. In Olive Cotton, such a strategy revealed Cotton’s lifelong relationship with photography. It highlighted the fact that, despite periods of financial hardship and artistic isolation, and in spite of the stifling effect of domineering men around her (including Dupain, her first husband), Cotton’s commitment to photography was unwavering. Ennis made a convincing case for Cotton to be recognised as among the best twentieth-century Australian photographers, a belated recognition and arguably one still not fully realised.

In this new biography, Ennis does not need to make an argument for Dupain as a serious photographer or for his photographs to be taken seriously. Rather, her credentials as biographer, curator, and photo historian open the possibility for a new reading of Dupain’s work against the somewhat tumultuous world of his personal life and the often racist and patriarchal landscape of Australian cultural politics. There are some challenging themes at play here: the rise of eugenic thinking in interwar Australia and Dupain’s family’s relationship with these ideologies as well as the protracted process of mid-century divorce and the reductive value of women as housekeepers and carers, as seen in many of Dupain’s personal relationships. There is a careful, measured craft to Ennis’s writing. She peels back the different strata of Dupain’s existence, blowing the sand from the abstraction, but refrains from arriving at moralising or finite assessments of the man himself.

The chapters dedicated to specific Dupain photographs are enlivened in new ways by this biographical dimension. We learn about Dupain’s withdrawal from the photographic community, with a few exceptions: his friendly relationship with photographer, Harold Cazneaux; his apprenticeship in the studio of Cecil Bostock, and his brief participation in the short-lived collective 6 Photographers. Dupain considered himself much more in conversation with a technical investigation of photography happening in Europe. Ennis shows how these associations manifest in his work: one example being the solarisation (over-exposure of the whites) of a female nude portrait titled ‘Homage to Man Ray’ (1937). In retreating from a local circle of artists, Dupain turned to the literature of D.H. Lawrence and Aldous Huxley as guides for engaging with the modern world. These authors are referenced in overt ways in his photographs through titles, props, and subject matter. Ennis uses the chapters dedicated to specific images to unravel what has previously been seen as certain, confident, and celebratory about Dupain’s photography, highlighting a much more vulnerable side to the images and the artist.

The vacant architectural scenes of Dupain’s photographs and, in other instances, their celebration of anglophone leisure culture, speaks to a great amnesia in ‘Australian’ art of an Indigenous past, present, and future. Ennis acknowledges this, but also gestures to sporadic inflections of Aboriginal culture in Dupain’s own life. In parentheses we learn that Max and Diana gave their first-born child an Aboriginal name. The Dupain’s home in the Walter Burley Griffin-designed harbourside suburb of Castlecrag was set amongst ‘a mixture of old bush and new plantings of thousands of indigenous trees and shrubs’. Nevertheless, Dupain’s photographic practice, which drew heavily from his domestic environment in his final years, gravitated towards flower studies of introduced species: magnolia, Argentinian orchids, and lilies. These are elements of Dupain’s biography (displaying a consciousness of Indigenous culture) and photographic practice (complicit in erasing an Indigenous past or presence) are unreconciled in this volume and point to avenues for future exploration.

Here Ennis demonstrates that the role of the feminist biographer and art historian is not confined to recovering the lost or marginalised practices of women artists (although there is certainly much work to be done on that front). She shows that an important task lies in confronting the larger-than-life male figures of Australian art: revisiting their work alongside its ‘autobiographical, social, cultural and historical moorings’. This does not necessarily operate to displace artists like Dupain from a national imagination, but it definitely casts their photographs in a new light.

Comments powered by CComment