- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Photography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Getting the picture

- Article Subtitle: Can photographs stop wars?

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Has any photograph ever changed the course of a war? It is a claim as old as photography itself, expressing a profound faith in the power of the image to communicate and move. However, like most religious statements, it does not stand up to rational scrutiny. It relies on the coincidence of two highly improbable phenomena. First, it assumes that everybody sees the photograph in question. This was a more contingent possibility in the analogue age, and it is even less certain in our image-saturated times.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

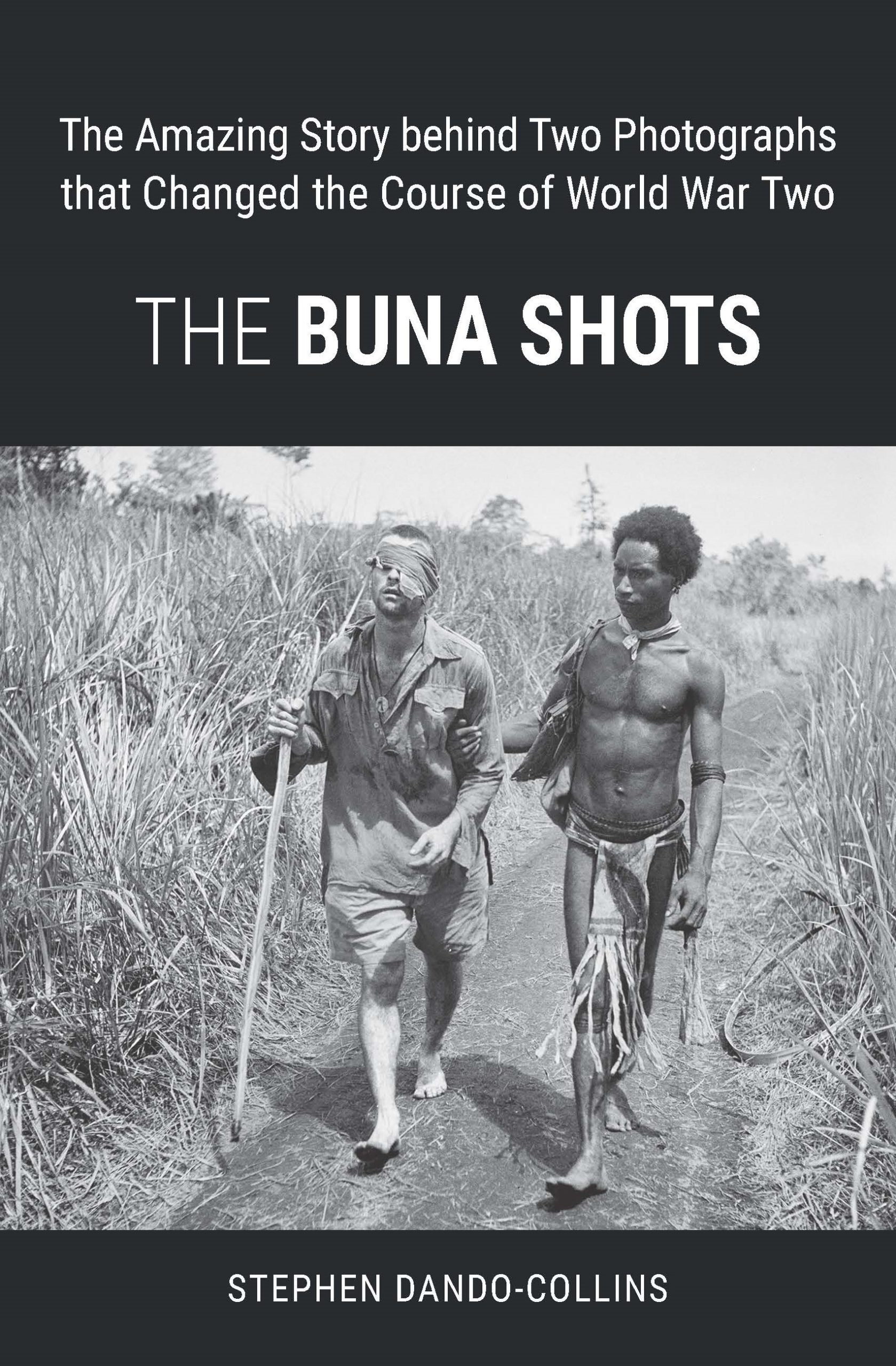

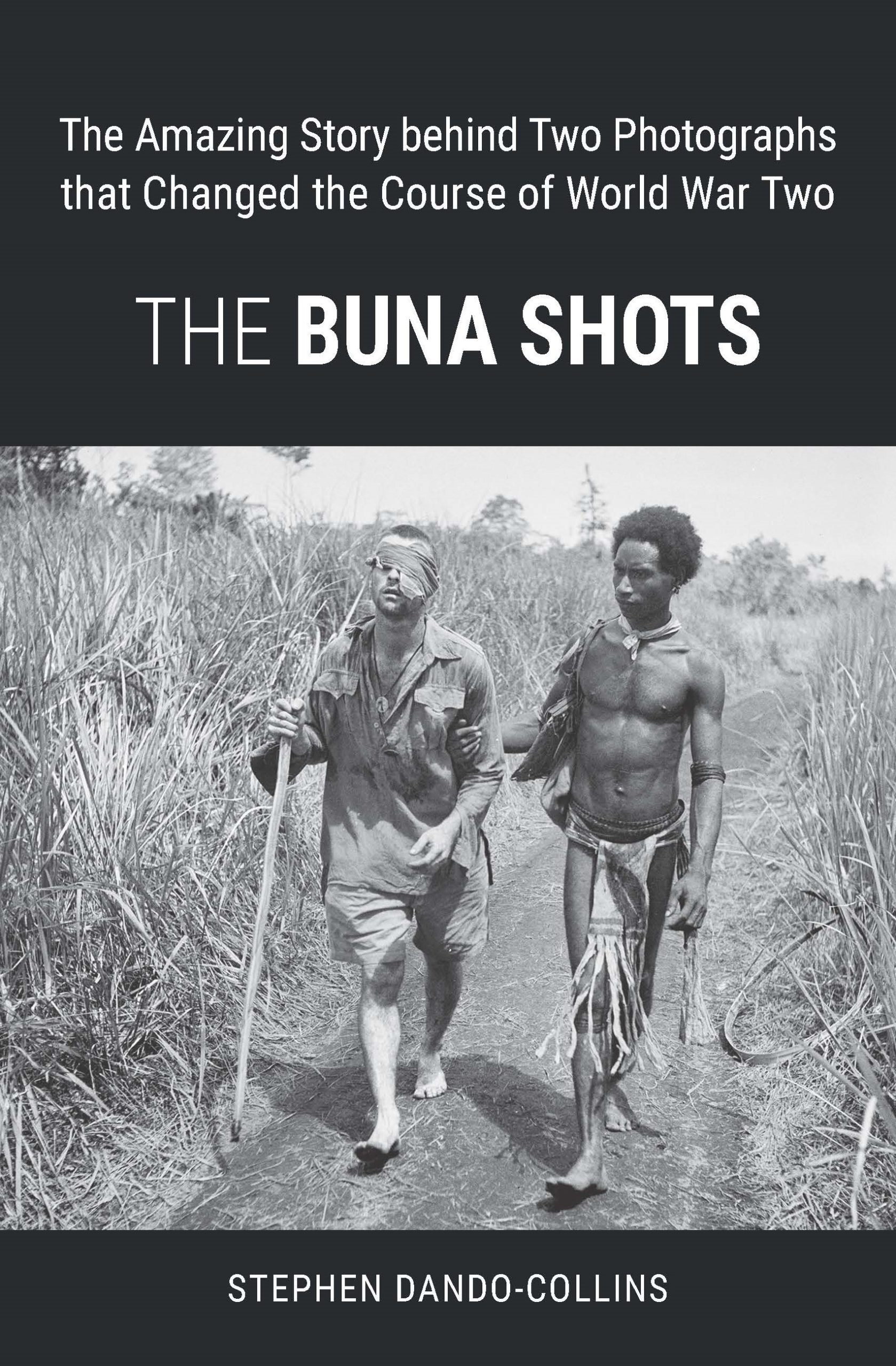

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Kevin Foster reviews ‘The Buna Shots: The amazing story behind two photographs that changed the course of World War Two’ by Stephen Dando-Collins

- Book 1 Title: The Buna Shots

- Book 1 Subtitle: The amazing story behind two photographs that changed the course of World War Two

- Book 1 Biblio: Arden, $39.95 pb, 278 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.readings.com.au/product/9781923267060/the-buna-shots--stephen-dando-collins--2024--9781923267060#rac:jokjjzr6ly9m

Two images commonly presented as evidence of photography’s persuasive powers both come from the Vietnam War: Nick Ut’s 1972 ‘Napalm Girl’ photograph of Kim Phuc, her clothes burnt from her body by a napalm strike, fleeing with other terrified children past impassive South Vietnamese troops on a road outside Trang Bang; and Eddie Adams’s photograph of South Vietnam National Police Chief, Nguyen Ngoc Loan, executing captured Vietcong fighter Nguyen Van Lem with a single shot to the head on a street corner in Saigon during the 1968 Tet offensive. These have, at one time or another, been lauded as, respectively, the photograph that ended the Vietnam War, and the image that turned the US public against the war. Each of these claims is as bold as it is inaccurate.

In the case of Nick Ut’s photograph, by 9 June 1972 when it ran on front pages across the world, the Vietnamisation of the war was in full effect. As the South Vietnamese military assumed more of the tasks formerly performed by their allies, US troop strength in Vietnam fell from a peak of more than 500,000 in 1968 to 69,000 when Ut took his photograph. Two months later, on August 12, the last US ground combat troops left Vietnam. The napalm that gravely injured Kim Phuc was dropped by the South Vietnamese Air Force. This was not the photo that ended the Vietnam War; the US administration had already given up and most of its personnel had been repatriated.

As for Adams’s ‘The Execution’, and the claim that it captured ‘the instant when Western opinion about the Vietnam War shifts fundamentally’, scholarship has shown that it actually had the opposite effect. When the photograph appeared above the fold on the front page of The New York Times on 1 February 1968, it was corralled by headlines and captions that framed the action as a tough but necessary response to the enemy’s unprecedented assault on US bases and Vietnamese population centres over the Tet holiday period: ‘Street Clashes Go On in Vietnam; Foe Still Holds Parts of Cities: Johnson Pledges Never to Yield’; ‘A Resolute Stand – Enemy Toll Soars’. In the aftermath of the publication of the photograph, US public opinion polling recorded a rise in support for Lyndon B. Johnson’s conduct of the war.

Three dead soldiers after the Battle of Buna Gona, New Guinea, 1943 (Granger/Alamy)

Three dead soldiers after the Battle of Buna Gona, New Guinea, 1943 (Granger/Alamy)

All of which is a long prelude to saying that Stephen Dando-Collins’s The Buna Shots is a good book with a misleading subtitle. Its strengths lie in the power, propulsion, and clarity of its narrative. It does a fine job of detailing how war photographers George Silk and George Strock put themselves in the right place at the right time to capture the images that defined their careers: respectively the photograph of New Guinean Raphael Oimbari leading a temporarily blinded George ‘Dick’ Whittington to medical assistance on Christmas Day 1942, and the image of three dead Americans half buried in the sand on Buna Beach, taken a week later. Stricken by malaria, both shuttled between the battlefronts on the northern coast of New Guinea and the 2/9th Australian General Hospital at Seventeen Mile, outside Port Moresby. While recuperating, they milked their contacts and kept their ears open for information about where the action was, climbing off their hospital beds to get themselves there. Both were hardy, uncomplaining, and brave – in Silk’s case, recklessly so. On several occasions, to the astonishment of his colleagues and the consternation of military personnel, Silk exposed himself to enemy fire to ensure that he got the image that he wanted. Both men suffered for their pictures, but in the end, each got the photographs he wanted.

That government censors then refused to publish their most prized images, arguing that the public were not yet ready for such graphic depictions of the fighting and its costs, was a source of enormous frustration to both men. Silk acted decisively: bypassing his employers, the Australian Department of Information (DoI), he had his photograph of Whittington, and two other censored images of fierce fighting at Giropa Point, cleared by US military censors before passing them on to Life magazine. Soon after the Whittington photograph was published in the United States on 8 March 1943, Silk was summoned to Sydney and summarily dismissed from the DoI. Hired as a staff photographer by Life, he went on to cover the Allies’ European campaign and remained at the magazine for the rest of his distinguished career.

Back in the United States in the first weeks of 1943, Strock worked with Life’s executive editor, Wilson Hicks, and more than a dozen senior editorial staff to select the best of his photographs from the Buna campaign. While the first of these images was cleared by censors and published in the 15 February 1943 issue of the magazine, the key photograph of the three dead Americans was held back. With the country still shaken by the Japanese attacks on Pearl Harbor and the military situation in the European and Asian theatres of conflict ‘close to the nadir for the Allies’, President Franklin Roosevelt and his Secretary of War, Henry L. Stimson, were convinced that public morale was dangerously fragile. Accordingly, they directed the Office of War Information (OWI) to stick to morale-boosting images of GI gumption and to protect the American public from the bloody truth of what its servicemen were enduring in North Africa and the Pacific.

Over the first quarter of 1943, the balance of the war began to shift decisively. The Russian victory at Stalingrad, the turning of the tide in the Western Desert, where the Allies were getting the upper hand over Rommel’s Afrika Korps, and in March the sinking of eight Japanese troop transports bound for Port Moresby, portended the beginning of the end for the Axis powers. In this context, as George Roeder detailed in The Censored War (1995), a book conspicuously missing from the bibliography here, as 1943 progressed it became clear to Roosevelt and Stimson that the larger threat to victory was not deepening public demoralisation but growing complacency – a conviction that the war was already all but won. This manifested itself most alarmingly in rising rates of absenteeism and softening productivity in US military industry. In the light of this, it was determined that what the public needed now was not coddling but shock therapy. Strock’s iconic Buna photographs were released for publication in September 1943, among more than one hundred other images previously held back by the War Department’s Bureau of Public Relations, where they had been stored in a file macabrely designated The Chamber of Horrors.

Over the next two years, in an effort to motivate a stubbornly distracted US public to knuckle down and put in the production effort needed to finish the war once and for all, the censors and the OWI released increasingly graphic images of US dead, from the soldiers stripped of their boots, lying in the slush at Malmedy on the Belgian-German border after they surrendered and were massacred, to the lone GI, dead at his station, slumped forward over his rifle, his belongings scattered around him, his uniform spattered with dirt, blood, and maggots.

The publication of Silk’s photograph of Oimbari and Whittington, and Strock’s image ‘Three Dead Americans’ were, for different reasons, consequential. Yet neither changed the course of the war. If the eventual publication of Strock’s photograph heralded a welcome loosening in US censorship, the release of Silk’s photograph resulted in a further tightening of already strict regulations dictating where Australian photographers could go and what they were permitted to depict.

Sad to say, in the decades since they banished Silk to his glittering career across the Pacific, Australian censors in the Department of Defence and the military have barely shifted from their view that the media’s presence on the battlefield is a problem to be managed rather than an asset to be supported and deployed. In the digital age, where information is a more powerful weapon than ever before, Defence’s obdurate refusal to engage constructively with the fourth estate diminishes the ADF’s effectiveness, ill-serves the public, and imperils the nation. It’s time they got the picture.

Comments powered by CComment