- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: ‘Subject to his birth’

- Article Subtitle: The biography of a prince

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

At the beginning of Hamlet (Act I, sc. 3, 177 ff.), Laertes warns Ophelia against becoming too attached to the young prince.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Christopher Allen reviews ‘James Fairfax: Portrait of a collector in eleven objects’ by Alexander Edward Gilly

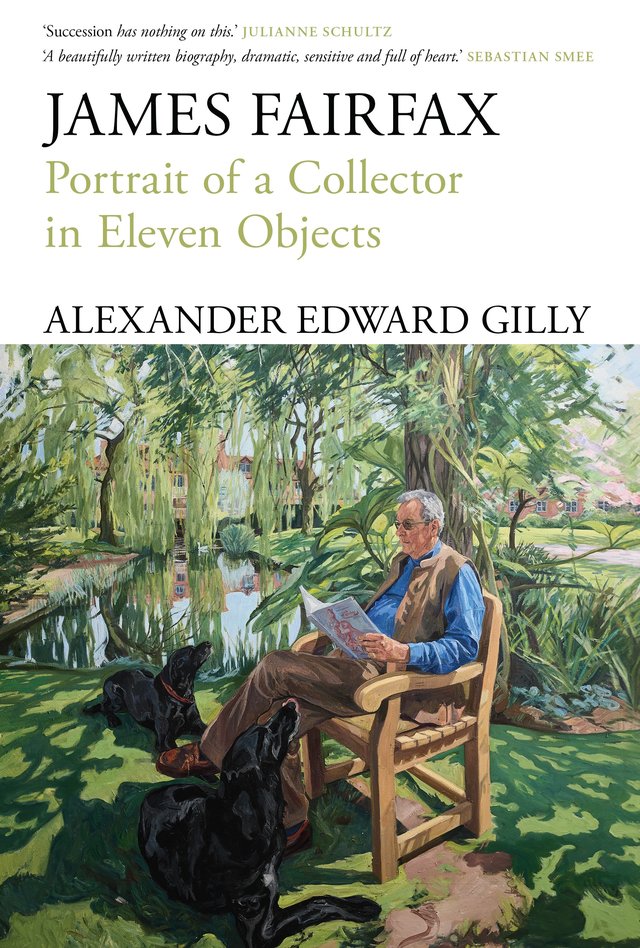

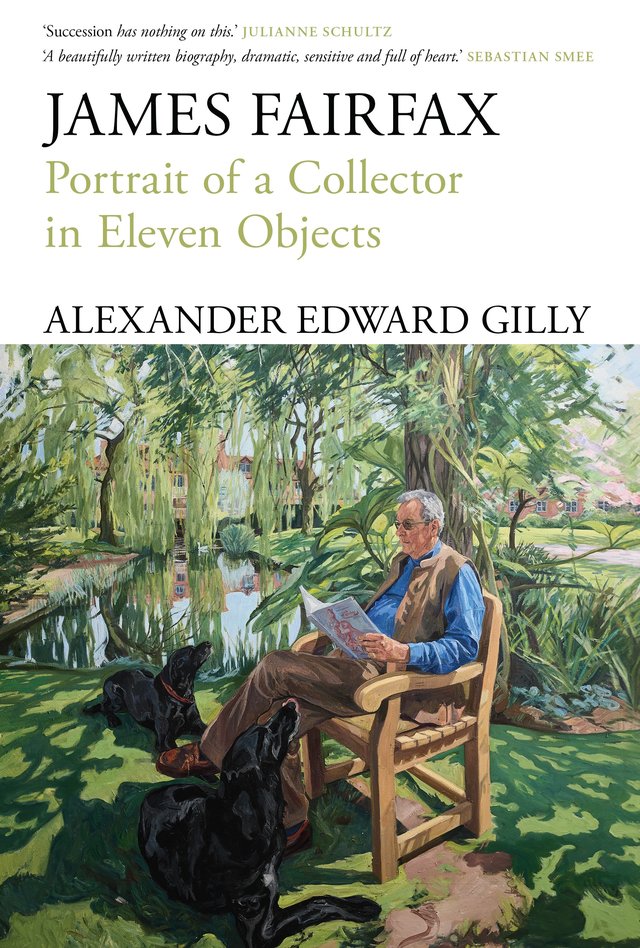

- Book 1 Title: James Fairfax

- Book 1 Subtitle: Portrait of a collector in eleven objects

- Book 1 Biblio: NewSouth, $49.99 hb, 343 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.readings.com.au/product/9781761170249/james-fairfax--alexander-edward-gilly--2024--9781761170249#rac:jokjjzr6ly9m

This passage is important for the understanding of the play and its much-dissected hero, for though Hamlet epitomises the complex, curious, but doubt-ridden intellectual world of the sixteenth century, he is not free to be the independent, self-fashioning individualist that Jacob Burckhardt saw as the true Renaissance man. He cannot carve for himself; the ruler is paradoxically subservient to the body politic of which he is the head.

So is the scion of a great commercial family, and the life of James Fairfax, as told in this absorbing book by his nephew Alexander Edward Gilly, reminds the reader of nothing so much as the biography of a prince, especially in some oriental kingdom in which potential heirs have to vie for the favour of a capricious or stubborn old monarch, and then, after his death, assassinate each other in a series of palace coups.

James Fairfax (1933-2017) was born into the greatest press dynasty Australia had yet seen. His great-grandfather John Fairfax had bought a share in The Sydney Herald in 1841 and subsequently changed its name to The Sydney Morning Herald. It was the beginning of the golden age of newspapers, as the modern steam-powered rotary press allowed them to be printed in vast numbers and at a previously unimaginable speed. The Fairfax family became very wealthy and built a series of splendid mansions, mainly in and around Bellevue Hill in Sydney.

James’s father was the formidable Sir Warwick, who, for half a century, bestrode the stage of Sydney’s newspaper world like a colossus. He was a tall and impressive patrician, yet personally quite diffident, intellectual, and donnish. He was high-minded and had a principled conception of the moral and political integrity that his paper should represent, as well as the unquestioning conviction that he should personally be the ultimate guardian and arbiter of that integrity; publishers and editors were to follow his direction.

For a shy and rather awkward man, Sir Warwick had a surprisingly turbulent personal life. James was his son by his first wife, the beautiful Betty, but in 1945 they divorced, something then almost unheard of among the respectable. After another marriage and divorce, Sir Warwick married his third wife, Lady Mary, who produced a second son, the so-called Young Warwick, setting the scene for one final drama and the collapse of the Fairfax dynasty.

James was a quiet and gentle boy. Indeed, it is hard to read this book without being impressed by his good nature. He showed a capacity for steadfastness and courage in his professional career, and yet he seems to have risen above bitterness and resentment even towards people who behaved appallingly or betrayed him.

There was never any doubt what James would do with his life. He was the heir to the Fairfax empire and was raised to assume its crown. He was accordingly sent to Geelong Grammar and then to Oxford – perhaps the happiest time in his youth – and then returned to learn the ropes of the newspaper business. But much of his life was shaped by the difficulty of dealing with his father, to whom James was never close, perhaps ultimately because of his homosexuality.

The first great confrontation occurred when he and the other board members had to force Sir Warwick to step down from the chairmanship for a time during the scandal of his second divorce and remarriage in 1959. Against much resistance, Sir Warwick was persuaded to sell half his shares to James before his new marriage, to safeguard family control over the company. But the hardest of all was forcing Sir Warwick to resign and allow James to assume the chairmanship in 1977. After this, Lady Mary became an embittered harpy, raising Young Warwick in the conviction that they had been robbed and that he would one day have to win the empire back.

James’s chairmanship (1977-87) was, on the whole, a happy period for the Fairfax company; unlike his father, James did not believe in dictating to his managers and editors, and as a result Fairfax papers could take different political lines. The National Times, for example, was far more radical and controversial than the relatively conservative Herald. In the background, however, the newspaper landscape was beginning to change fundamentally; Rupert Murdoch, who had been at Geelong and Oxford with James, had established The Australian in 1964, and was by far the most brilliant, agile, and decisive newspaperman of his generation. The stories of James’s attempts to defend the company against Rupert’s growing power are reminiscent of Croesus efforts to forestall the rise of Cyrus in Herodotus. They make engrossing reading, and the book vividly conveys the sense of urgency and the momentousness of what was at stake.

Unfortunately, although James ably guided the company through these battles with a uniquely dangerous competitor, his half-brother became convinced that John Fairfax Ltd would fall prey to corporate raiders or that James and the other members of the family on the board would in some way betray him. So in August 1987 he borrowed $2.25 billion and bought everyone else out. Two months later, the stock market crashed, and subsequently interest rates exploded. Young Warwick was ruined, and the family lost control over the business they had successfully nurtured for almost a century and a half.

The tragic irony of all this was that James had been planning to retire in 1991 in any case, and to pass the chairmanship on to Young Warwick. But Warwick, egged on by his mother, couldn’t wait. As for James, he was left with a colossal fortune and spent the remainder of his life building his art collection and then giving most of it away to Australian galleries and museums.

The book, which is engagingly written, is structured around the idea of certain analogies between objects in James’s collection and events in his life. Sometimes the conceit feels a little strained, but often it is quite effective in shedding light on James’s inner life and character. This intelligent, civilised, dutiful, and thoughtful man was quite reticent about his feelings; and yet the many beautiful works that he acquired and with which he endowed our museums speak revealingly of a refined sensibility and a quiet passion for beauty.

Comments powered by CComment