- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Uncertain masculinities

- Article Subtitle: The frailties of patriarchy

- Online Only: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

In his seminal book I Don’t Want To Talk About It (1997), Terrence Real outlines how contemporary men, within the frameworks of white-supremacist capitalist patriarchy, must undergo a severing of self from self, and self from community. Real identifies how the so-called masculine power attained through this severing comes from a ‘one down’ position in which the struggle for ‘power over’, rather than ‘power with’, is a central doctrine of what he calls ‘patriarchal masculinity’. This power over, rather than power with, is similarly manifest in international governance, statehood, community and the family unit itself – and it is even manifest in the representation of male characters in Australian literature.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Tim Loveday reviews ‘Fragile Creatures: A memoir’ by Khin Myint

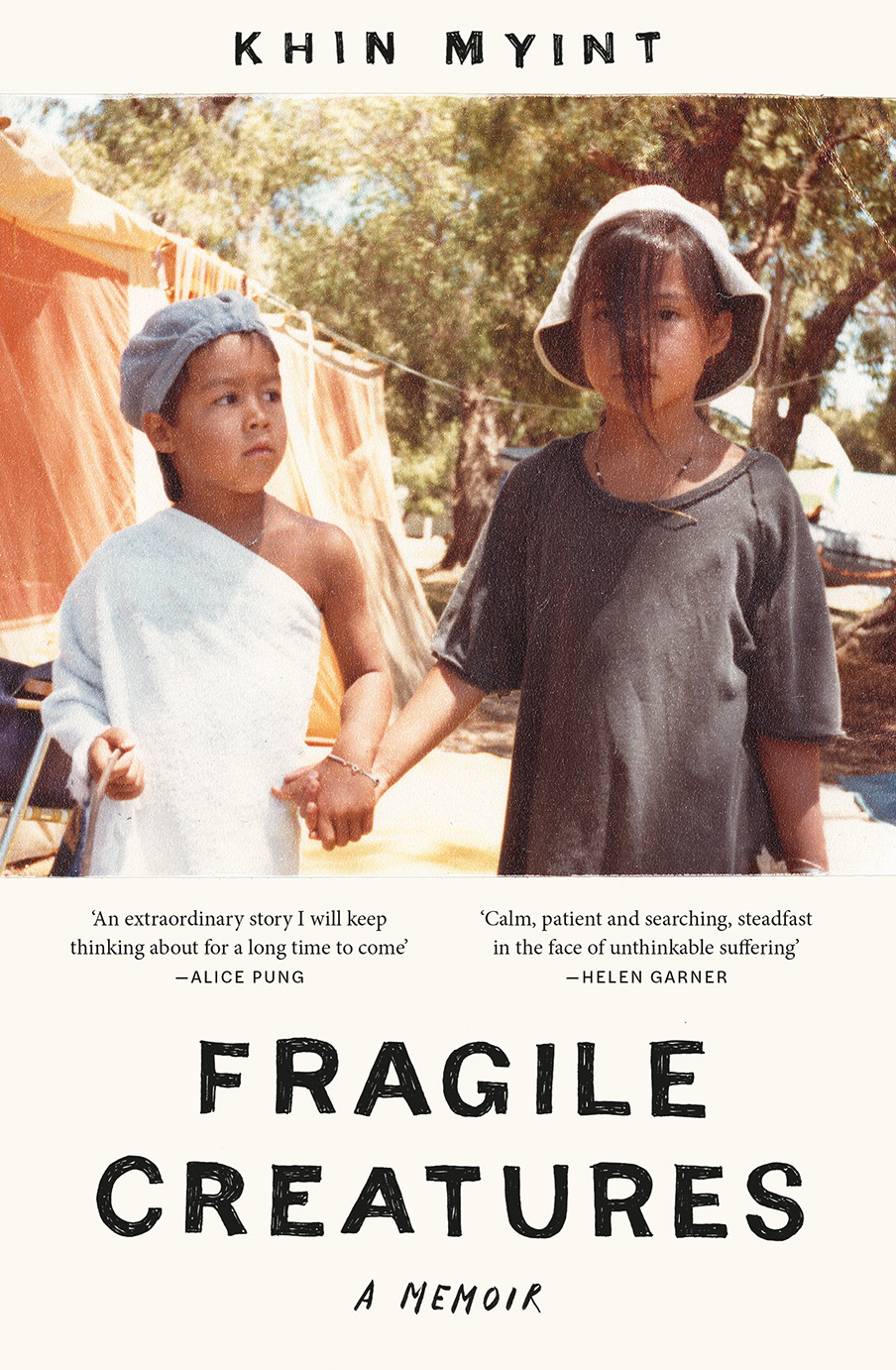

- Book 1 Title: Fragile Creatures

- Book 1 Subtitle: A memoir

- Book 1 Biblio: Black Inc., $34.99 pb, 272 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.readings.com.au/product/9781760645144/fragile-creatures--khin-myint--2024--9781760645144#rac:jokjjzr6ly9m

This is why Fragile Creatures, Perth-based Australian-Burmese writer Khin Myint’s first book, is such a revelation. He tells two stories simultaneously, braiding together seemingly disparate threads, each drawn with deep insight, humility and vulnerability reminiscent of bell hooks, who called for a new popular culture that teaches men ‘the art of the possible’.

The first thread follows Khin’s older sister Theda, who has struggled through years of a mysterious illness that has rendered her entirely dependent on their mother. For more than a decade, Theda has cycled through the depressing machinery of the medical system, with medical practitioners and quacks alike, all with their own opinions about what is wrong with Theda. Is it psychological? Is it physical? Khin’s long-separated parents disagree, and Khin himself isn’t sure.

Khin worries that if he outlives his mother, he will not be able to play the carer role that Theda desperately requires. Theda, meanwhile, has ordered an assisted suicide drug online, what she calls ‘a last resort’. This decision sends Khin into a state of reckoning as he explores his and Theda’s childhood in early-1990s suburban Perth. He wonders whether the violence and dislocation they experienced have irreparably shaped their futures. In doing so, Khin contemplates his family home, one where he and Theda felt trapped between their English mother and their Burmese father, a man who repeatedly chastised them for being ‘too Western’.

At school, things were not much better. Khin and Theda were bullied horrendously, with Khin subjected to daily bashings, loads of trash in his locker, and children whispering ‘bit nippy in here’ as he passed. In one tragic scene, Khin recounts the brutalisation of a fellow Asian student Simon. Drunk at a party, Simon is given so much cannabis that he falls unconscious, at which point a group of boys strip him naked and string him up to a hills hoist using bedsheets, before throwing eggs at him. No doubt, the racist violence that Khin experiences at school mirrors the extreme anti-Asian rhetoric that was taking hold across Australian at that time, rhetoric championed by the likes of Pauline Hanson, while in Western Australia white-nationalist Jack van Tongeren was gaining significant notoriety for fire-bombing Chinese restaurants.

The second storyline follows Khin as he travels to upstate New York hoping to talk to his ex-fiancée Rachel. Having lived in Perth with Khin, Rachel has returned home to visit her family, promising Khin that she would be back soon. Then her tone alters suddenly: ‘Just be a fucking man,’ she screams at Khin over Skype – all this from a woman who had once explained identity politics to him (‘If you’re Black, the culture perceives you a particular way, and it affects how you feel about yourself’).

Nevertheless, Khin remains hopeful. On the advice of his psychologist, he decides that the trip might glean some answers. What he is confronted with is devastating: Rachel is a different person, openly antagonistic and dismissive. After a single coffee and an agreement that they will meet again, Khin is shocked when he learns that, barely a day later, the police have come to see him at his low-budget hostel. They agree to meet again, but Khin is shocked when a local issues a temporary Order of Protection for Rachel. Alone and unable to leave the country, Khin is caught in a new limbo, with the woman who purported to love him only months earlier mobilising her so-called liberal family, the police, and judicial systems against Khin. Here, Myint writes:

I thought about the implications of an older foreign brown man coming to see a beautiful young white female local … An old news story about an active shooter at Virginia Tech snuck into my mind along with a lot of other worries.

While both storylines are centred on race-hatred, and draw to mind critiques of performance politics, contemporary white feminism, and the precarity of our health systems, this book is also enmeshed in discourses of uncertainty, never more so than in its laser-point focus on masculinities.

Where so much of masculinity discourses preach certainty of self, Myint asks questions that signal to the limitations of his own perspectives. In doing so, he draws attention to those points of connection we have even with those who have hurt us: the desire to make sense of the world. It would be easy for Myint to condemn those around him to villains intent on hurting him. Instead, he offers a blueprint for a masculinity of compassion, of accepting uncertainty as the human continuum that binds us but also brings us together.

While he does not shy away from voicing his frustration, Khin paints a portrait of Rachel as a human, longing to find her place in the world, longing to belong. Likewise, his father, who exerts a mild machismo over his family, experiences a psychic dislocation perpetuated by a physical one as he longs for his idealised home country of Burma while simultaneously struggling to conform to modes of contemporary Australian masculinity as an Asian man. Even the bullies are given such worldly affordances; they are fragile creatures forever at odds between the will to connect, the need to fit in, and the feeling that they must exert so-called power over one another to do so.

Fragile Creatures thus returns us to that deeply ontological search for connection.

Again, I am reminded of bell hooks, who called for ‘a progressive popular culture that will teach men how to connect with others, how to communicate, how to love’.

Comments powered by CComment