- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Theatre

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Playing for real

- Article Subtitle: On democracy and drama

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

James Shapiro, a professor of English at Columbia University in New York, starts his new book with an epigraph listing two dictionary definitions of ‘playbook’: ‘[a] book containing the scripts of dramatic plays’, but also a ‘set of tactics frequently employed by one engaged in a competitive activity’. The Playbook turns on bringing these two definitions together. It argues that the Federal Theatre Project that developed in the United States between 1935 and 1939, as part of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal program, was effectively scuppered by the political machinations of ambitious Texas congressman Martin Dies. In 1938, the wily Dies succeeded in setting up the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), with himself at its head. HUAC became notorious during the Cold War, under the direction of Joseph McCarthy, for its persecution of political dissenters. Shapiro’s thesis is that its nefarious influence began earlier, with the democratic principles he regards as inherent in theatre being peremptorily shut down by Dies’s political opportunism. Shapiro presents this conflict as a forerunner of more recent American culture wars driven by Pat Buchanan in the early 1990s through to Donald Trump in the present day.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Paul Giles reviews ‘The Playbook: A story of theatre, democracy and the making of a culture war’ by James Shapiro

- Book 1 Title: The Playbook

- Book 1 Subtitle: A story of theatre, democracy and the making of a culture war

- Book 1 Biblio: Faber, $39.99 hb, 380 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.readings.com.au/product/9780571372768/the-playbook--james-shapiro--2024--9780571372768#rac:jokjjzr6ly9m

There is much to admire about this book. It is well written, in an accessible style, and meticulously researched, with extensive archival material relating to both the theatrical and political realms. To my mind, however, the cause and effect relation that Shapiro adduces between a flourishing democratic theatre and a repressive political apparatus is somewhat forced. There are many reasons why a national theatre never fully emerged in the United States: the rapid rise of Hollywood in the 1930s; the continental geography of the United States, which made touring by theatre companies more time-consuming and expensive than in Europe; and also the long-standing American suspicion of centralised, state-sponsored initiatives in the arts. Shapiro tends to romanticise Hallie Flanagan, the professor at Vassar College who was chosen to run the Federal Theatre, while demonising Dies as ‘a tall and charismatic Texan in his late thirties who worked his way through eight cigars in the course of a day’s hearing’. These stereotypes veer towards the melodramatic, an idiom that could be construed as commensurate with the broad readership for which Shapiro clearly aims, as he presents these complicated issues in terms of clashes of personality.

This book is an odd hybrid between an academic and a popular work, one that is well informed but seems determined, perhaps too determined, to wear its learning lightly. There is a highly informative ‘bibliographical essay’ encompassing seventy pages at the end of the book but no footnotes at all, and the publisher’s attempt to accommodate both a scholarly and a more general audience is evident. There are, to be sure, many fascinating anecdotes and details relating to the Federal Theatre Project, including accounts of such innovative productions as Orson Welles’s 1936 version of Macbeth set in nineteenth-century Haiti. It is also interesting to learn how, when it opened across eighteen cities in October 1936, the theatrical version of It Can’t Happen Here, Sinclair Lewis’s 1935 novel warning about the dangers of fascism, succeeded in avoiding the kind of censorship that had quickly become institutionalised in Hollywood. Whereas the film studios took care to avoid political controversy in order to maximise their audiences and profits, the Federal Theatre was more open to taking risks and much less inclined to subjugate its dramatic priorities to commercial concerns.

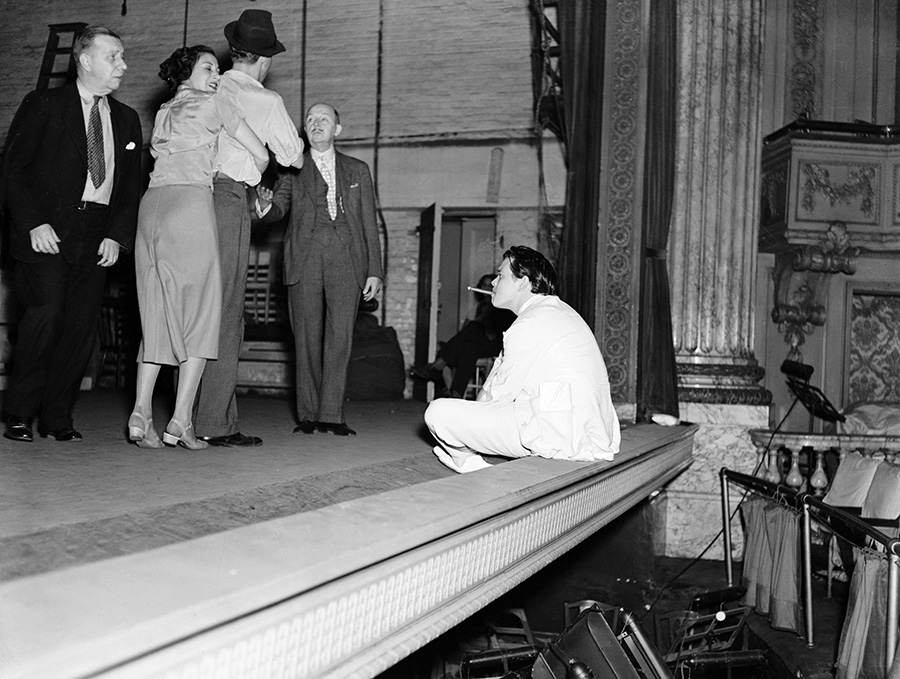

Arlene Francis, Joseph Cotten, and Harry McKee, with director Orson Welles in rehearsal for the Federal Theatre Project production of Horse Eats Hat at Maxine Elliott’s Theatre, 1936 (Bill Waterson/Alamy)

Arlene Francis, Joseph Cotten, and Harry McKee, with director Orson Welles in rehearsal for the Federal Theatre Project production of Horse Eats Hat at Maxine Elliott’s Theatre, 1936 (Bill Waterson/Alamy)

Shapiro’s book boasts a blurb on its back cover from the distinguished English playwright David Hare, who claims ‘the attacks on the Federal Theatre in the US in the 1930s presage every smear today being directed at the unique achievements of the subsidized arts and public broadcasting in the UK’. This advertises the presentist slant of Shapiro’s argument: the way he represents Dies’s HUAC attacks as foreshadowing current events. Yet Emmet Lavery, who worked as a Hollywood scriptwriter as well as being a Federal Theatre playwright in the 1930s, recalled when reflecting on his career in 1976 that ‘in the theatre particularly – well, in films also – there are so many questions of taste and style involved that the acceptance or rejection of a script may have nothing to do with the personality of the author, or even the worth of the enterprise. So many peripheral factors.’ It is telling that even Lyndon B. Johnson, who was of course instrumental in passing Civil Rights legislation in the 1960s, voted in 1939 to defund the Federal Theatre, which suggests that this decision did not emerge purely from political partisanship.

Through the very depth of its detailed research, this book gives a sense that the controversies of arts funding at this time were a more tangled business than the author himself is prone to suggest in his more adversarial moments. Chronicling how Senator Robert Reynolds of North Carolina mocked the sympathetic treatment of interracial dating in Federal Theatre plays, Shapiro suggests ‘it would be hard to outdo Reynolds in sheer nastiness’. Perhaps so, but vituperative politics are commonplace everywhere, and Illinois Congressman Everett Dirksen’s attempt in 1939 to attract newspaper coverage by stringing together the titles of Federal Theatre plays and reading them aloud with sarcastic commentary is a tactic all too familiar in Australia as well as America, where the titles of academic grant projects are often ridiculed loudly by conservative politicians and their media backers.

Ultimately, this kind of political playbook is predictable and not especially interesting. The problem is that, by taking sides so polemically, Shapiro risks his own book becoming another instrument in the culture wars that he overtly deplores. As a scholar in residence at the Public Theatre in New York City, which has offered free performances of Shakespeare in Central Park since 1962, Shapiro obviously has skin in this game, and he follows Willa Cather in preferring the dramatic presence of a ‘living human being’ to what she called in 1929, in a snipe at the emerging mass media, ‘pictures of them, no matter how dazzling’. Shapiro goes back to Alexis de Tocqueville to justify his lament that ‘a more vibrant theatrical culture extending across the land might well have led to a more informed citizenry, and, by extension, a more equitable and resilient democracy’.

I found this open advocacy for public theatre to be the book’s least persuasive aspect. In 1880, there were 5,000 theatres in 3,500 locations across the United States, but by 1929 Hollywood was attracting audiences of 110 million every week, and by the 1950s television had begun to exert its national hegemony. The consequent consolidation of American theatre in the major cities of New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles was driven by many factors beyond the personal agenda of Martin Dies. Although Shapiro tells his story engagingly, the larger historical hypothesis seems somewhat strained. Nevertheless, his framing of the Federal Theatre as an important project in its own right during a particular historical era results in an unusual analysis of the subject, one that juxtaposes national politics and cultural history in valuable ways. The Playbook is enjoyable and enlightening in its description of theatrical experiments during the Roosevelt era. It pays tribute to various bold pioneers in this federal drama project who brought controversial matters relating to race, gender, and the rise of fascism to the attention of the American public.

Comments powered by CComment