- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Nifty Nev

- Article Subtitle: A comprehensive demolition job

- Online Only: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

Neville Wran (1926-2014) was a great Australian success story. His early childhood was spent in the Sydney suburb of Balmain, long before it was gentrified. He won a scholarship to study at the selective Fort Street Boys’ High School and then completed a law degree at Sydney University. Wran subsequently enjoyed a lucrative career as a Sydney lawyer, ultimately becoming a Queen’s Counsel (1968).

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Lyndon Megarrity reviews ‘The Assassination of Neville Wran’ by Milton Cockburn

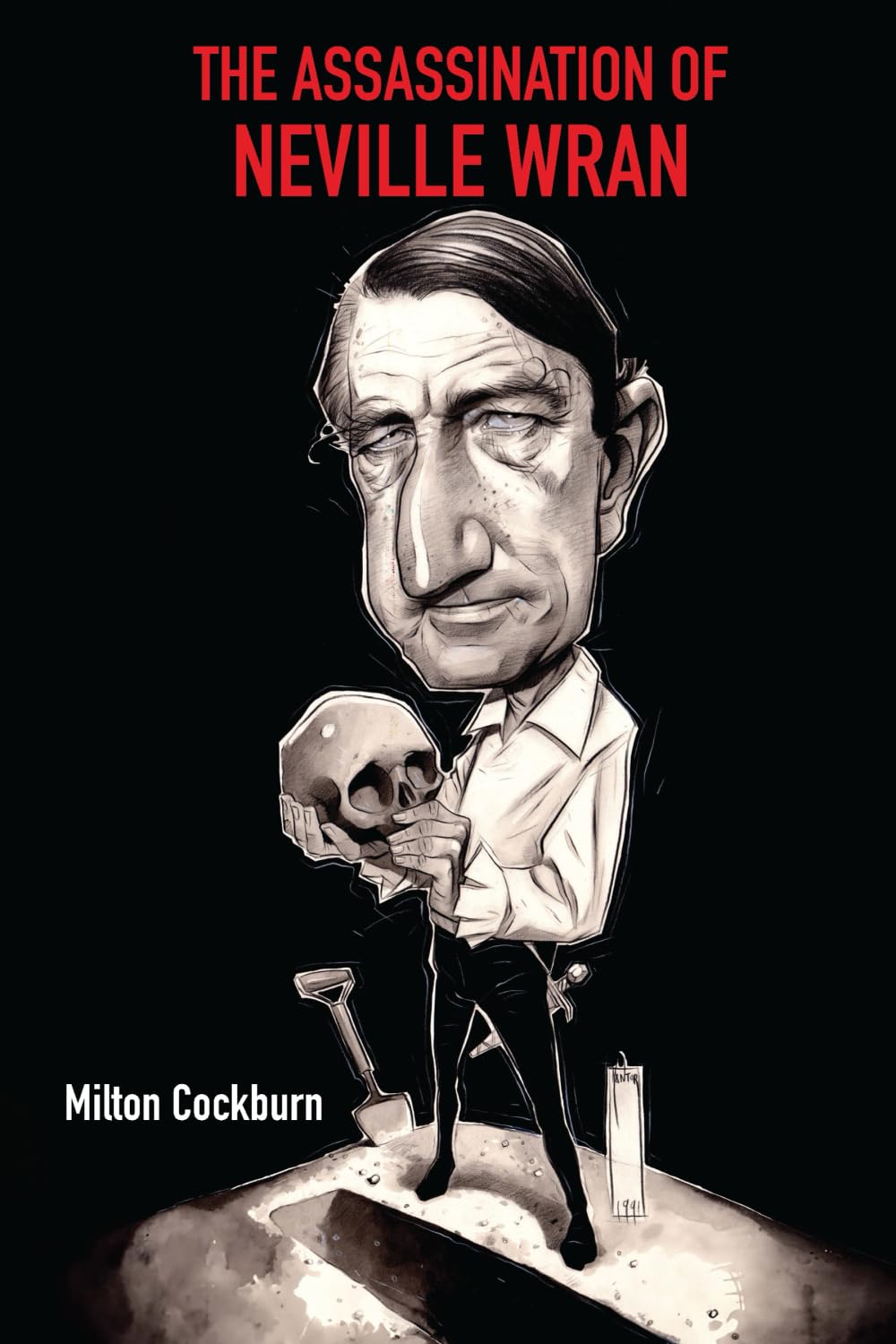

- Book 1 Title: The Assassination of Neville Wran

- Book 1 Biblio: Connor Court Publishing $29.95pb, 246 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

An urbane and committed leader with a talent for communicating his government’s agenda with the public, Wran could occasionally appear to be hardened and cynical about the world of politics. There is an oft-repeated, well-worn anecdote about Wran’s considered feedback regarding a proposed ‘Reconciliation, Recovery, Reconstruction’ slogan for Bob Hawke’s 1983 election campaign: ‘If the greedy bastards [i.e. the electors] wanted spiritualism, they’d join the fucking Hare Krishna.’ Colourful comments by the premier such as ‘in politics … unfortunately, you have to clamber over a number of dead bodies to get anywhere’ may go part of the way to explaining why Wran unwittingly made himself a target for investigative journalists seeking to expose corruption.

The Assassination of Neville Wran painstakingly examines allegations of corruption made against Wran and his government over the years. The author, Milton Cockburn, usefully defines corruption as ‘the use of power or influence for illegitimate private gain, usually in the form of money’. This clear definition influences the contents and structure of the book.

Cockburn is well qualified to write this book. He was an adviser to Premier Wran for four years and subsequently, as a Sydney Morning Herald editorial writer and columnist in the 1980s, informed the public about the Wran era as it progressed. With co-author Mike Steketee, he also published an unauthorised biography of Wran in 1986. While clearly proud of his association with Wran, Cockburn is by no means a hagiographer and acknowledges both the strengths and weaknesses of Wran and his ministers.

One by one, chapter by chapter, allegations of corruption made against Wran are systematically addressed and shown to be demonstrably false. In many cases, journalists hooked by the thrill of the chase forgot to question the biases, reliability, relevance, and veracity of their sources, to seek alternative perspectives, and to provide solid corroborative evidence. For instance, journalists relied on hearsay evidence to somehow connect Wran to Sydney crime figure Abe Saffron: yet it was Wran himself who initiated an inquiry on Harbourside, the company that in the 1980s owned the lease to Luna Park, to determine whether or not Saffron had links to the entertainment venue. As Cockburn remarks, ‘This is very strange behaviour by a premier who, according to the ABC, had a friendship with Saffron and had intervened to ensure Saffron got the lease.’

As Cockburn, notes, there were some instances of official corruption in the Wran era, most notably in the police force. There is no evidence, however, that Wran himself bore any personal responsibility, although the author suggests that the premier ‘failed to detect when public attitudes began to shift in favour of a desire to reform the police’ and failed initially to tackle the issue head-on.

The author also discusses broader administrative issues that were not, by their nature, corrupt, but that raise perennial questions of how governments should balance sectional interests with those of the wider electorate. The Wran government’s political and financial support for Kerry Packer’s use of the Sydney Cricket Ground for his World Series Cricket initiative was at least in part a piece of corporate welfare, although the author notes the wider benefit for cricket fans and other stakeholders. Elsewhere, Labor’s granting of a licence to administer the game of Lotto to a consortium involving the Murdoch and Packer media companies was above board and transparent, but Cockburn intimates that Wran hoped that such ventures would alter a media environment that was frequently antagonistic towards Labor.

While well written, the author’s comprehensive demolition job on the flimsy basis of corruption charges relating to Wran does not require several chapters to clearly and convincingly drive the point home. Two condensed essays on this topic would have been enough to satisfy all but the most stubborn contrarian. In addition, more effort to expand the potential readership beyond New South Wales was needed: it is an undeniable fact that Australians care about their own state and what happens federally but can find it difficult to engage with the political history of another state. Greater interstate comparisons and broader discussion of universal political themes would have been helpful in this regard.

The author’s passionate criticisms of contemporary journalists who have been careless with their historical research are mostly fair. However, willingness to believe in sensational allegations and report unproven assumptions has always been a feature of the mass media, and in the age of 24/7 news and digital competitors, the concerns so eloquently raised by the author will probably only increase.

Comments powered by CComment