- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Theatre

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Noni’s grip

- Article Subtitle: Driven by an urge to tell stories

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In 1983, actor Noni Hazlehurst was invited to London by Robyn Archer to be part of Archer’s new cabaret Cut and Thrust. Hazlehurst, less than a decade out of acting school and having just been fêted in Cannes for her performance of Nora in the film adaptation of Helen Garner’s Monkey Grip (1982), was ‘thrilled to bits’.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Diane Stubbings reviews ‘Dropping the Mask’ by Noni Hazlehurst

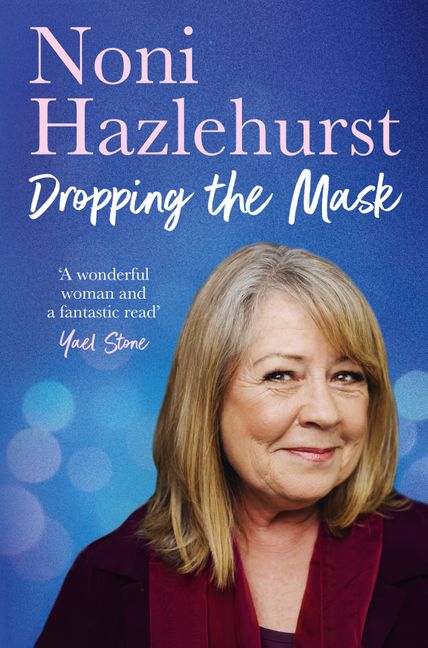

- Book 1 Title: Dropping the Mask

- Book 1 Biblio: HarperCollins, $39.99 hb, 381 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.readings.com.au/product/9781460759042/noni-hazlehurst--noni-hazlehurst--2024--9781460759042#rac:jokjjzr6ly9m

Hazlehurst always perceived herself to be both English and Australian, and she believed that she would eventually settle full-time in London and make her career there. Working with Archer on Cut and Thrust not only pushed her ‘to really stretch myself in every way – physically, vocally, politically’; it also led to director Richard Cottrell offering her the role of Nora in a production of Henrik Ibsen’s The Doll’s House at Bristol’s Old Vic. Hazlehurst knew she had reached a turning point.

One constant that emerges through Hazlehurst’s memoir, Dropping the Mask, is the steep learning curve she embarked upon – both intellectually and emotionally – once she left her parents’ protective cocoon when she was seventeen. Not that she was deprived of books and stories as a child – her mother, a gifted storyteller, had taught her daughter to read before she started school – but the books available to Hazlehurst were ‘[h]eavily curated’.

Flinders University, where Hazlehurst enrolled to study acting, having been first rejected by NIDA, was a ‘radical departure’. Under the tutelage of industry stalwarts Wal Cherry and George Whaley, she was introduced to Brecht and Stanislavski, and to the proposition that she was not obliged to merely regurgitate the intellectual ideas that were placed in front of her. Slowly, she discovered the value of her own voice and her own opinions.

This flourishing sense of who she was and what she wanted persuaded Hazlehurst to decline the role in Cottrell’s The Doll’s House. In part, the decision was influenced by her feelings of homesickness, and her sense that England was a place that, despite her heritage, ‘would always see me as a colonial’. More significantly, Hazlehurst found herself unable to identify with Ibsen’s heroine. Despite having worked in Australia in numerous historical dramas – for example, Bob Herbert’s play No Names, No Pack Drill (1980), alongside Mel Gibson, and television productions such as The Sullivans (1976-83), Ride on Stranger (1979), and Waterfront (1984) – Hazlehurst was ‘keen to tell stories about contemporary [Australian] women’.

Hazlehurst acknowledges the impact working with playwright Dorothy Hewett had on her determination to return to Australia. Not long out of university, Hazlehurst was cast in the inaugural production at Perth’s National Theatre of Hewett’s now-classic play The Man from Muckinupin (1979), soon reprising the twinned roles of Polly and Lily (‘Touch of the Tar’) Perkins for a revamped STC staging (1980). Anyone lucky enough to have seen Hazlehurst in Hewett’s play will remember the radiance of her performance, her seamless transformation from one sister to the other, the intensity and humanity she bought to both.

When deciding whether to forge her path in Australia or England, Hazlehurst was reminded of Hewett’s advocacy for Australian writing, her ‘anti-colonial political radicalism’ and her desire ‘to express the life of her own country’. Hazlehurst knew she wanted to do the same – the rest, as they say, is history. Hazlehurst built on her reputation as one of the finest and most versatile actors in the country with forays into reality television, arts management and policy, and social justice advocacy (the latter an extension of her twenty-four years as a presenter on Play School, the stage upon which, she insists, she learned more about her craft than any other). In the process, Hazlehurst distinctively embodied on our stages and screens – in works such as Fran (1985), Nancy Wake (1987), Little Fish (2005), Candy (2006), The Beauty Queen of Leenane (2014), and, most recently, Mother (2015 and still touring) – many unforgettable women, both contemporary and historical.

Anyone looking for a memoir dripping with caustic insider gossip will be disappointed. Dropping the Mask largely adheres to the maxim ‘if you can’t say something nice about somebody, don’t say anything at all’. Not that the book is without its share of self-deprecating humour and acerbic asides, particularly with respect to politicians. John Howard’s prime ministership stoked ‘meanness, divisiveness and fearmongering’, while Tony Abbott’s ‘hypocrisy is breathtaking in its cynicism and opportunism’.

One of the few hints of opprobrium comes in the revelation that STC’s 1980 production of Hamlet (in which Hazlehurst played Ophelia) was, in part, scuppered by British director William Gaskill being ‘obviously attracted to Colin Friels [who was playing Hamlet], which created some unnecessary tension’. (Having been fortunate enough to see that production, I might say that what seemed an ‘unholy mess’ to its cast was, to a teenager who had never before encountered Hamlet, miraculous.)

While Dropping the Mask often reads like an accumulation of diary entries, there is no denying the cosiness and charm of Hazlehurst’s writing, the intimate sense that these are anecdotes she is sharing with you over a glass of wine. There are few surprises, and few masks are in fact dropped, primarily because Hazlehurst, as both performer and advocate, has always been consummately honest with her audience. Her prodigious body of work is its own proof that she is driven, as she says, not by money and fame, but by the urge to tell stories and, without exception, to tell them truthfully.

Comments powered by CComment