- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: France

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: ‘Impression, sunrise’

- Article Subtitle: Art and politics collide in a pulsating narrative

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

No movement in the history of art is so beloved as that which we label ‘Impressionism’, and no artists’ names are as familiar as those of its stars: Manet and Monet, Pissarro and Morisot, Degas and Renoir. But why did Impressionism blossom at a particular moment in Paris and in that form? Sebastian Smee’s brilliant new book offers compelling answers.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Peter McPhee reviews ‘Paris in Ruins: Love, war, and the birth of Impressionism’ by Sebastian Smee

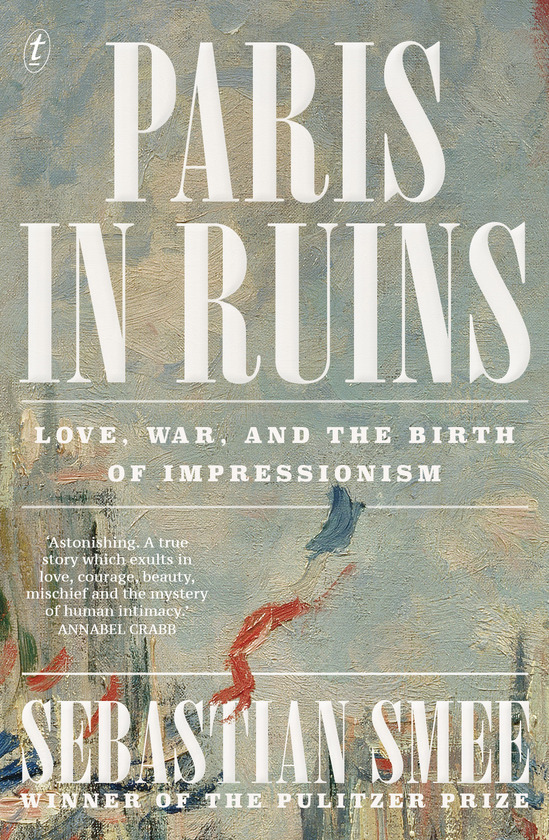

- Book 1 Title: Paris in Ruins

- Book 1 Subtitle: Love, war, and the birth of Impressionism

- Book 1 Biblio: Text Publishing, $36.99 pb, 381 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.readings.com.au/product/9781923058057/paris-in-ruins--sebastian-smee--2024--9781923058057#rac:jokjjzr6ly9m

Smee’s explanation for the emergence of Impressionism is broadly in line with those of other art historians who have seen the movement as an avant-garde reaction to the stultifying ‘academic’ art patronised by the élite, male-dominated Académie des Beaux-Arts and approved of by the Emperor Napoleon III. The favoured subjects at the annual salons were ornate historical canvases, sentimentalised views of plump peasants, and naked women from classical antiquity or ‘the Orient’. This was the world of wealthy stylists such as Bouguereau, Cabanel, and Gérôme.

There are no sharp turning points in the history of art, and Smee places the origins of Impressionism years before the term was first used in 1874. He locates its origins in Manet’s explosively erotic Luncheon on the Grass (1863) and Olympia (1865), which shocked the pompous world of approved ‘academic’ art at a time when republicans and socialists were increasingly contesting the authoritarian regime of Napoleon III. Manet, Renoir, and others often took to painting outdoors, ‘rendering the physical world as colored light broken into discrete units’.

Smee differs from other art historians in his close attention to the Franco-Prussian war of 1870, the defeat and collapse of the Second Empire, the suffocating Prussian siege of Paris in September 1870-January 1871, the birth of the Third Republic, and the radicalism and vicious repression of the Paris Commune in March-May 1871. Art and politics constantly collide in Smee’s pulsating narrative.

In March 1871, republicans, socialists, and their Parisian supporters rebelled against the armistice with Prussia, seized control of the city, and created what Karl Marx called the first communist revolution. The subsequent ‘bloody week’ massacre by the army in May killed up to 30,000 Communards, many of them with spectacular levels of cruelty. Shelling and fires destroyed, among many other buildings, the Tuileries Palace and the Town Hall. The year of violence further fractured relationships between artists with different politics.

Bismarck’s proclamation of the German Empire at Versailles and the loss of Alsace-Lorraine crowned the humiliation of what Victor Hugo dubbed l’année terrible. Such was the depth of suffering during the siege, of internecine violence, and of the sense of loss of the eastern provinces, that artists sought solace in capturing the sensory experiences of the natural world. Impressionism was born ‘in loose, unfinished-looking brushstrokes that captured colored light and sensations of transience’, in opposition to the art establishment’s emphasis on ‘a moralistic vision with high degrees of finish and laborious displays of skill’.

Smee’s other innovation is to focus on the politics and passionate friendship of Édouard Manet and Berthe Morisot who, with Edgar Degas, were the only prominent Impressionists who remained in Paris during the traumatic months of the Prussian siege and the Paris Commune. He restores to Morisot her rightful place among the great names of Impressionism, as well as teasing out the painful depth of her love for Manet (she eventually married his brother Eugène).

Joseph Guichard, who had taught Morisot and her sister Edma to paint, was outraged by the avant-garde to which she now belonged, and wrote to her mother that Berthe should ‘go to the Louvre twice a week, stand before Correggio for three hours, and ask his forgiveness’. We don’t know whether the message was passed on, but Berthe was as stalwart as she was gifted.

Impressionists sought to capture the world in motion, exemplified in the railway age sweeping the west of Europe, painting outdoors to capture the sensory impressions of nature and images of ordinary people at leisure. An art critic commented at the first exhibition of Monet, Pissarro, Morisot, Renoir, Degas, Cézanne and others, in 1874, that ‘they are impressionists in that they represent not the landscape, but the sensation produced by the landscape’. This was the first of eight Impressionist salons up to 1886. As the new Third Republic prospered, so did Impressionism.

Among the many painters who fled the capital in 1870 as Prussian troops approached was Claude Monet, then aged twenty-nine, and his young family. While in London, Monet was exposed to the canvases of J.M.W. Turner and others, and marvelled at how they captured the distinctive light of fogs and the exhilarating speed of railways. When Monet finally returned to France in late 1871, he painted river scenes and railways at Argenteuil, then famously a sunrise over the harbour in his hometown of Le Havre: ‘Impression, sunrise’.

It is curious that Smee refers to Monet and this painting only in passing. Limited as he is to using English-language sources, he misses the work of French scholars such as Dominique Lobstein (Monet et Londres [2004]), who have emphasised the impact of his London exile.

Smee has a rare talent for painting word-pictures, notably in his superb descriptions of the salons, and a keen eye for revealing details. He evokes the accelerating suffering of Parisians during the siege, as the 250,000 sheep and 40,000 cattle herded into the Bois de Boulogne at the start of the siege were succeeded by shops selling various grades of rats and, finally, the flesh of elephants from the zoo: ‘tough, coarse and oily’ noted a contemporary.

This is first-rate historical writing. Smee weaves stories of his artists, their suffering and passions, through his text. He creates, for example, a powerful image of Gustave Courbet, a towering talent with a matching ego who embraced the radicalism of the Paris Commune to the extent of creating a democratic successor to the Académie and its Salons and organising the ceremonial destruction of the Vendôme Column erected by Napoleon I following his victory at Austerlitz in 1805.

Smee describes his book as ‘an attempt to knit together art history, biography, and military and social history’. It is an uncommonly good synthesis of all of these, a scintillating narrative of an intense, violent period of military and political crisis in which artists were personally involved, at times tragically, and from which emerged intoxicating new forms of sensory expression.

Comments powered by CComment