- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Double memorial

- Article Subtitle: Elisions between love and truth

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In his famous outburst before the gathered men of the Symposium, Plato has Alcibiades declare that behind his ‘Silenus-like’ mask, Socrates is full of ‘divine and golden images’. He can see the gold where others see only the mask, and it is this which makes Alcibiades so desperate for the old man’s approbation.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Giacomo Bianchino reviews ‘John Berger and Me: A migrant’s eye’ by Nikos Papastergiadis

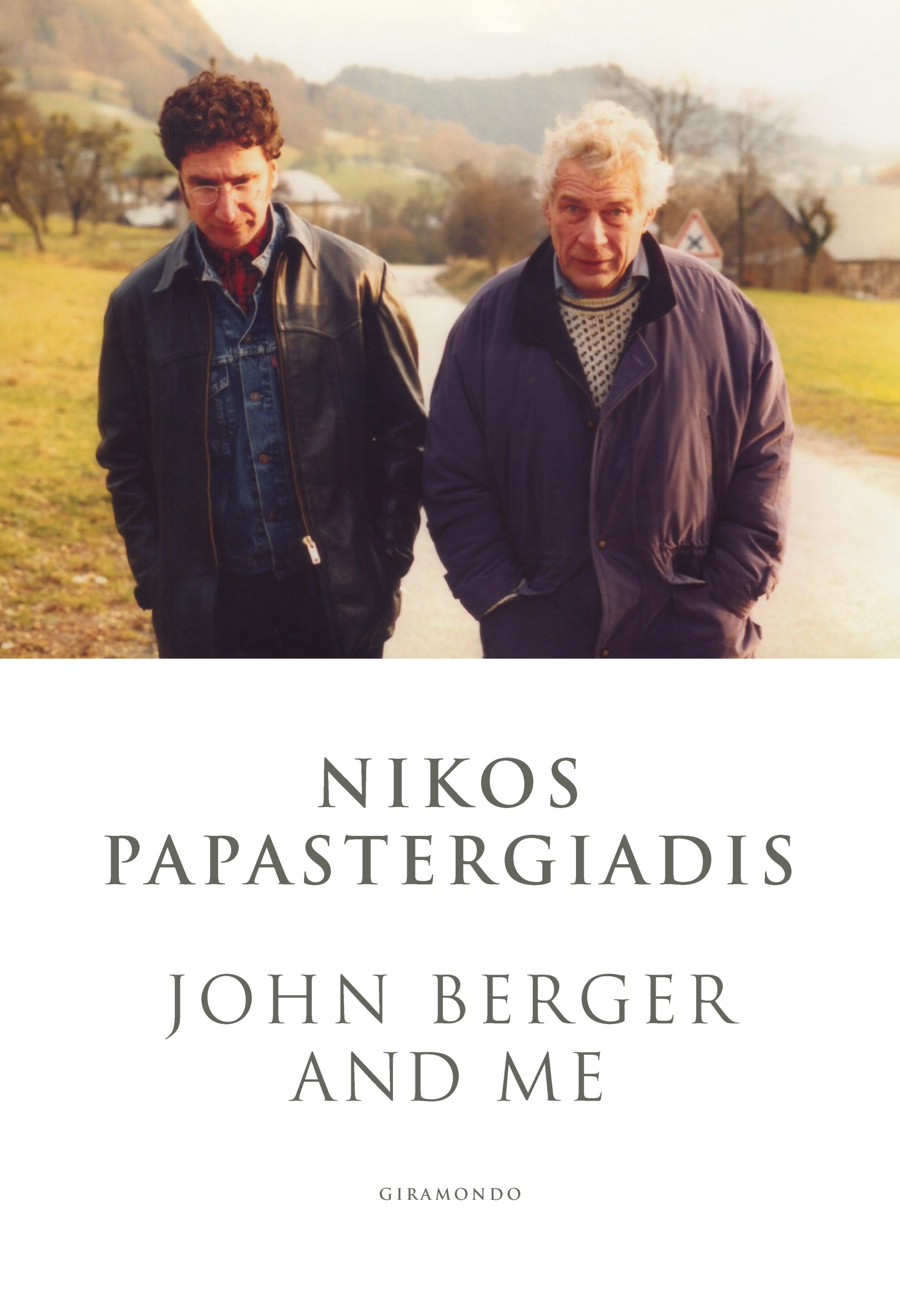

- Book 1 Title: John Berger and Me

- Book 1 Subtitle: A migrant’s eye

- Book 1 Biblio: Giramondo, $32.95 pb, 203 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

It is the relationship between student and mentor that Nikos Papastergiadis explores in his new book John Berger and Me. This theme is a difficult one, perhaps too complex to confine in a single genre. The book is, at times, a memoir, an homage, a tribute and gift, an elegy, a reflection, and an Upanishad (a sitting-at-the-feet-of-the-master-and-learning), but also a meditation on history. If I could reduce it to a sentence, this book is an attempt, following Berger’s own advice, to ‘hold everything dear’.

It tells the story of a two-decades friendship, beginning with Papastergiadis’s first trip to Quincy in the Haute-Savoie, where Berger had relocated in search of a greater authenticity in 1962. The book moves forwards and backwards in time, not only between different visits to the Berger house, but to anecdotes of the author’s relationship to his parents and grandparents, and the trace of his family history.

Among the anecdotes, the figure of Berger looms large in these pages. Papastergiadis’s attempts to get the man onto the page are not unlike the techniques of Cubism that Berger wrote about so eloquently: arranging a simultaneity of perspectives which always bring us back to the ‘totality’ that is the work itself. There is the sense of the physical-intimate, the heroic, the moral and saintly, the scholarly, and even the iconic.

But the question of Berger’s status is far from an objective one for Papastergiadis. He is handling not only a great man, but the man who shaped him. This shows in the vulnerability and tenderness with which Papastergiadis describes moments of genuine jealousy – like being forced to ‘share’ Berger with the actor Simon McBurney. There is also a dose of Eros, with the young man following Alcibiades in his grappling with the ‘gold’ inside his master towards a sense of unsettling desire.

If he cannot give the ‘totality’ that is John Berger, Papastergiadis finds other ways to carry off his homage. John Berger and Me is written in the same staccato as the late writer’s polemical works, and his novels from the 1980s. Papastergiadis is clear that his predilection for metaphor and simile have the same origin. He is not quite the stylist that his old master was, and there are moments of distracting formality in his writing. Indeed, he labours to remain a student of the advice he cites from his late mentor – to ‘write stories like the way you tell them when we are all gathered here in the kitchen’.

Some of these choices are about more than style: they are about time. The book is arranged in the sparagmatic paragraphs of G, the novel that won Berger the Booker Prize in 1972. The jumps across time are also distinctly Bergerian, presenting a challenge to linear time that the older man connected to the temporality of peasant life. Through meditations on Berger’s own works of love about this vanishing life-world, John Berger and Me touches history. The living man is brought into contact with his own family’s past, and to the question of the disappearance of the peasantry at large.

Papastergiadis – migrant, urbanite, academic – struggles in these pages with his own relationship to the people of the land. But the peasant is, for the author, only a metonym for a much more intimate struggle with paternity. We learn, during his moments of personal anecdote, that the author’s father suffers from dementia, and that he has begun the process of remembering and mourning a man who feels at times to him like a stranger. The work of John Berger and Me becomes a double memorial, where one person is grieved through and alongside another.

It is at this level that the book makes sense as a totality, rather than as a pile of fragments. The sense of fear about the loss of memory, and the ambivalence at farewelling two men who have had very different roles in one’s own self-creation, constitute the unifying tone of the book.

But such a fear and ambivalence sometimes rears its head as full-throated nostalgia for a lost world, and disgust at the present. It is hard to follow Papastergiadis all the way down this line, haunted as it is by a personal bitterness. Indeed, the author’s emotional inflection of the political raises an even more troubling question about Berger, whose flight to the Alps could be read uncharitably as the old romanticism of the Narodnik.

John Berger and Me leaves us with these questions. As a personal account, it is both tender and searching, a combination of hagiography and self-critique. The series of displacements, circling around the figure of the father, gives the work a nearly novelistic interest. In his desperation to show us the gold in John, it is true that Papastergiadis sometimes treats the man’s word as gospel. But this elision between love and truth is as old as the mentor: a figure with which few have the bravery to honestly deal.

Comments powered by CComment