- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Pacific

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: An oceanic turn

- Article Subtitle: How to understand the Pacific

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The publication of this book – and its reception – reveals a good deal about New Zealand as well as Australia in the past four or so decades, not least the remarkable rise of indigenous as a cultural and political keyword.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Bain Attwood reviews ‘An Indigenous Ocean: Pacific essays’ by Damon Salesa

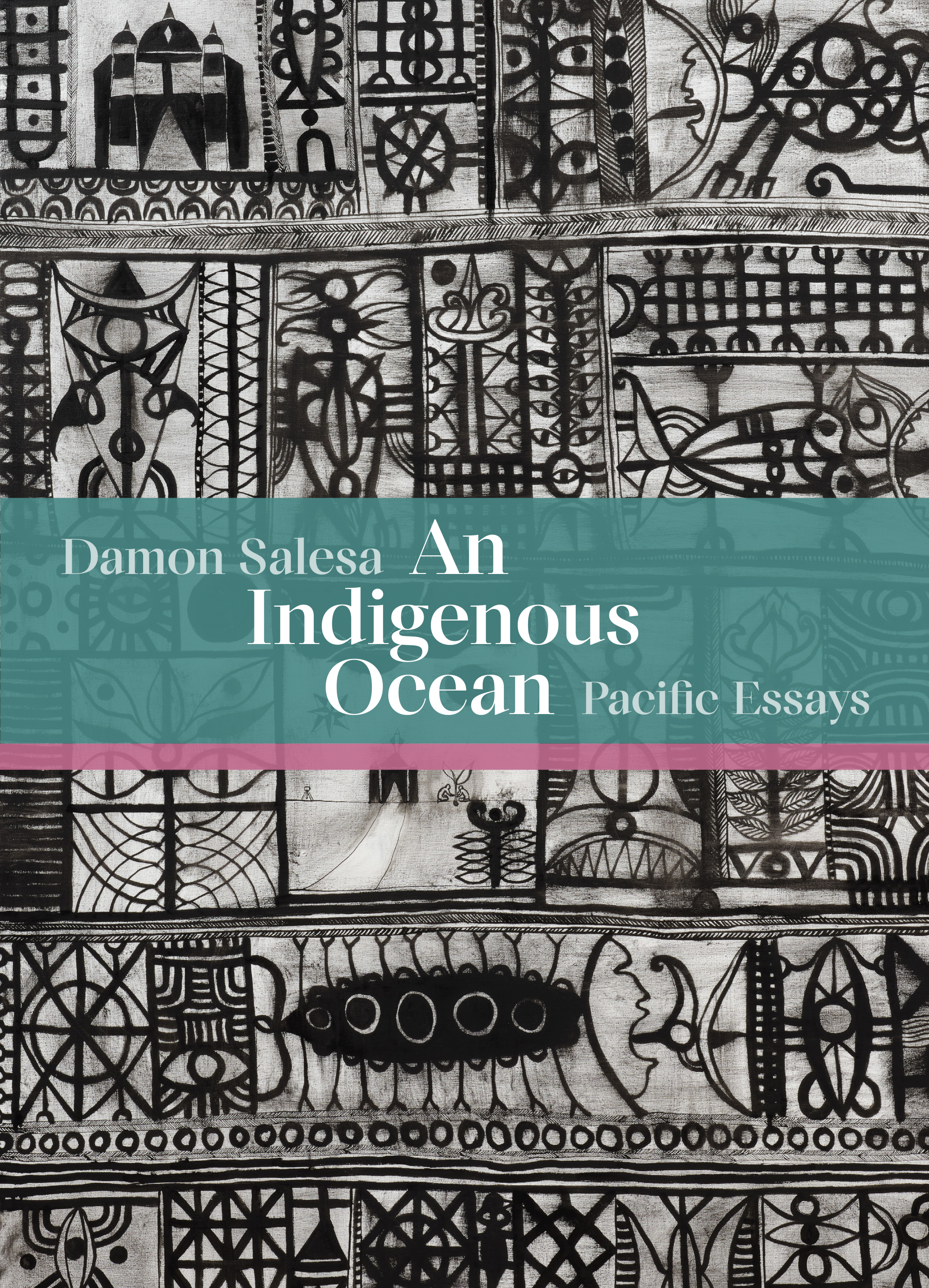

- Book 1 Title: An Indigenous Ocean

- Book 1 Subtitle: Pacific essays

- Book 1 Biblio: Bridget Williams Books, $49.99 hb, 381 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Damon Salesa has a proclivity for the essay. Nearly all of his academic writings have taken this form, and all but one of this book’s fifteen chapters are essays he has previously published. The essay seems to best suit his philosophical or reflective cast of mind. His abiding concern as a historian has not so much been the past but rather its legacies for indigenous peoples in the Pacific and more especially the ways in which history as a discipline, a discourse, and a practice determines the way the Pacific is understood and poses thorny problems for indigenous scholars because of its entanglement with imperialism and colonialism.

The deeply historiographical essays in An Indigenous Ocean have been organised into four parts: The Pacific World; New Zealand and the Pacific; Race and Colonisation; and Samoa’s Colonial Encounters. The imprint of the different political, social, cultural, and intellectual and institutional milieux Salesa occupied during the fifteen or so years he wrote most of them are evident to any informed reader, particularly if they read the book back to front.

When Salesa was a student at the University of Auckland in the 1990s, his most influential teachers included two Pākehā historians who were foregrounding the subjectivity, agency, and perspectives of indigenous people since colonisation: Judith Binney, the leading exponent of Māori history, and Hugh Laracy, an acolyte of New Zealand-born J.W. Davidson’s school of Pacific History at the Australian National University. Under their guidance, Salesa completed an MA thesis comparing the positioning and position of ‘half castes’ in New Zealand and Samoa. (He himself is the child of a Samoan father and a Pākehā mother.) In the late 1990s, a Rhodes scholarship took Salesa to Oxford to do his doctorate. Guided there by several eminent historians of empire and race, the research he conducted laid the basis for his only monograph, Racial Crossings: Race, intermarriage, and the Victorian British Empire (2011), which was informed by a marked Foucauldian turn in his scholarship that seems to have occurred after he became part of the North American academy. In the 2000s, he held a joint position in the Department of History and the Asian/Pacific Islander American Studies Program of the Department of American Culture at the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor before returning to his alma mater to become an Associate Professor of Pacific Studies and later the co-head of its school of Māori Studies and Pacific Studies. As a result of these two moves, Salesa became a champion of the interdisciplinary field known as Critical Pacific Studies, which is closely aligned with postcolonialism.

In the first part of this book, which most speaks to its title, Salesa journeys in the wake of what has been called an oceanic turn in the discipline of history. Indigenous scholars of the Pacific, such as the Tongan anthropologist Epeli Hau’ofa, have made significant contributions in this regard. Salesa, using the metaphor of an indigenous ocean to reframe historical enquiry into the world’s largest ocean and the innumerable islands that lie within it, sets out to bring to the surface the multiple ways in which the exponents of imperial, national, and global histories have repeatedly marginalised and even rendered absent the indigenous peoples of the Pacific and their ways of being in the world, and thereby laid the basis for powerful Euro-American systems of knowledge, the most recent example being the notion of an Indo-Pacific.

In his earlier essays, which appear in the second part of his book, Salesa was preoccupied with reconfiguring New Zealand’s history, arguing that it would look profoundly different if it were re-membered as one of the many archipelagos of islands and an oppressive empire-state in the Pacific. For example, he pointed out that about half of the 100,000 colonised people the New Zealand government enumerated in a census in the early 1920s were ‘Pacific Islanders’ to the north of Cape Reinga. Unfortunately, he has never completed the research that was needed to substantiate the historical significance of such startling facts.

Indeed, Salesa is no longer a practising historian, having become the vice-chancellor of Auckland University of Techno-logy following a stint as the University of Auckland’s first pro- vice-chancellor Pacific. But before this occurred, he had lost faith in history as a discipline that could empower indigenous people. He represents himself now as an interdisciplinary scholar rather than as a historian, and it is no coincidence that the last essay in An Indigenous Ocean tells a story about how one of Salesa’s Samoan mentors, Albert Wendt, became so disillusioned with the discipline of history in New Zealand that he rebelled, becoming a novelist instead. In his 2017 BWB Text, Island Time: New Zealand’s Pacific futures, it is evident that Salesa came to much the same conclusion about the discipline, though his way of resolving this problem was to become an interdisciplinary scholar.

To my mind, Salesa’s turn away from history makes the republication of his profoundly historiographical essays for a general audience a rather puzzling event: it is probably the cause of the book’s fragmented introductory essay and might even have prompted Salesa to call his book ‘a departure of sorts’. Yet this dissonance has gone unremarked in New Zealand, and within months of its publication the book was awarded the country’s most prestigious non-fiction book prize. It seems unlikely this accolade can be attributed simply to the book’s content, as much of Salesa’s exegesis, analysis, and argumentation is dense and expressed in typically academic prose, or to its impact, as it has prompted little discussion. Rather, its apparent success probably owes more to its representation as an indigenous product and the representation of its author as an Indigenous man of humble background who has made good.

This has evidently struck a chord with many benevolent-minded Pākehā who are feeling troubled by the fact that indigenous Pacific peoples suffer the worst poverty of any community in New Zealand, and unsure how they might engage in critically minded public debate about New Zealand’s future with those who can claim the authority of the indigenous and are calling for its decolonisation.

Comments powered by CComment