- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: ‘Unafraid to Be’

- Article Subtitle: 1888 Exhibition to Expo 88

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In 1888, Melbourne hosted a grand Centennial International Exhibition to mark a century of British occupation of the continent. There, a six-year-old girl called Ethel Punshon was excited to see that she had won a prize of two guineas for her needle-work – an embroidered red felt newspaper holder. Almost one hundred years later, as Brisbane prepared to mark the bicentennial with a modern ‘Expo 88’, Ethel – now known as Monte Punshon – was invited to become Expo’s roving ambassador, as perhaps the only person alive who remembered its predecessor.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Susan Sheridan reviews ‘A Secretive Century: Monte Punshon’s Australia’ by Tessa Morris-Suzuki

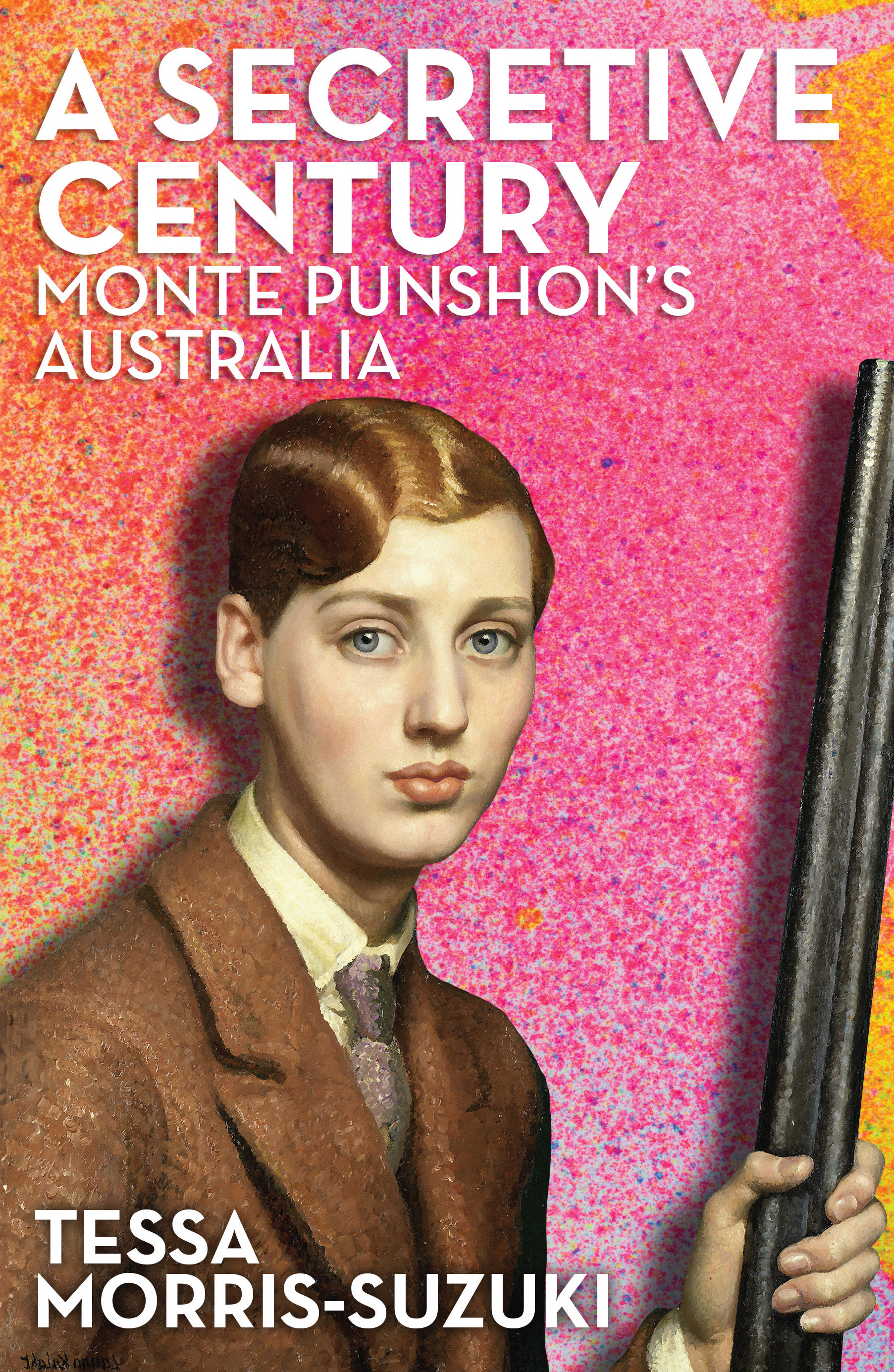

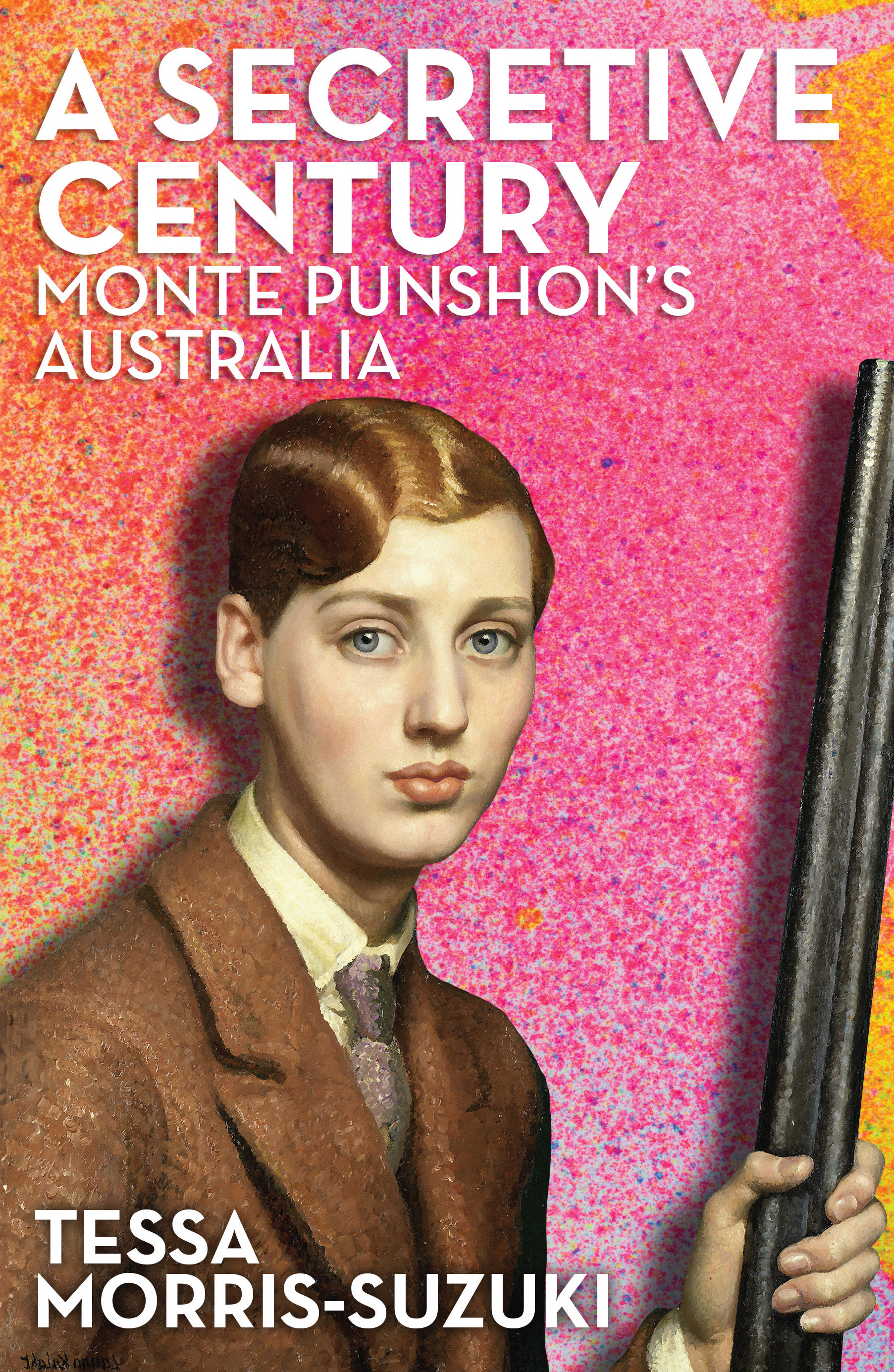

- Book 1 Title: A Secretive Century

- Book 1 Subtitle: Monte Punshon’s Australia

- Book 1 Biblio: Melbourne University Press, $35 pb, 330 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Punshon was famous for her longevity and for her many decades of nurturing connections with Japan, as a teacher and host to visiting students – an ideal choice, it seemed to Premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen and his advisers. When they learnt, some months later, that she was also being fêted as ‘the world’s oldest lesbian’ – she had come out in an interview with the Melbourne gay community paper, City Rhythm – they contacted her, questioning whether she was a suitable person to take on this role. Monte was offended. ‘It’s none of their blessed business,’ she told TheSydney Morning Herald. ‘Joh is trying to make out that women are criminals if they love one another.’

As it turned out, by the time Expo 88 opened, widespread corruption in Queensland had been exposed and Bjelke-Petersen, discredited, had retired from politics. Monte continued with her ambassadorial duties. But she took exception to being labelled: ‘I’m just me myself. I hate that name.’ That, and the public nature of press stories about her private self, distressed her. She could understand but not entirely share the gay liberation commitments of her younger friends – for her, the personal should never be political. Her lifelong attraction to women was central to her sense of self, but not something to be shared with people she had no connection with.

Throughout her long and adventurous life, it seems, a strong sense of herself as an individual guided Monte in following her own interests and desires, choosing her own loyalties. She grew up, in Ballarat and then St Kilda, in a stable middle-class family of modest means; her parents admired their clever daughter, and her younger sister, Hazel, remained her best friend. Always needing to earn her living, teaching was her main occupation; but she also pursued her scientific interests in electricity (which she had studied at the Ballarat School of Mines as a schoolgirl), photography, and radio (she took on jobs in both areas). She loved the theatre, and participated in both amateur and professional companies (in the latter usually as a teacher).

Theatre was a passion shared with the woman she called ‘the love of my life’, Debbie Sutton, with whom she lived (along with Hazel) for about a decade, when she was in her thirties. It was during this period of her life that she began to collect in a scrapbook images of women dressing in the modern ‘masculine’ styles of the 1920s, and of others who rejected conventional feminine roles – aviators, sailors, sportswomen, adventurers. As well, there were accounts of women living together as friends or ‘business partners’. She was perhaps constructing an identity for herself as an unconventional woman, one who crossed boundaries and was interested in women’s relationships and achievements.

Monte’s fascination with China and Japan prompted her to take classes in both Mandarin and Japanese, in Melbourne, and to travel. Her first overseas trip, in 1929, when she was forty-seven, was won in a raffle. She went to Japan, Manila, Hong Kong, and Shanghai; she also spent some time in Korea before returning home. Her last visit to Japan, almost sixty years later, was to celebrate the publication in Kobe of her memoir, Monte-San, in 1987.

The Japanese connection, which involved close friendships with several Japanese people living in Melbourne, led to her becoming a person of interest to the security services in the period leading up to the entry of Japan into World War II. Her friend and teacher, Moshi Inagaki, was, bizarrely, accused of ‘sabotaging the proper study’ of Japanese language and culture; but Monte and other women students were not regarded as dangerous. Indeed, Monte was employed as a warden at the Tatura detention camp to teach interned Japanese children.

After the war, Monte encountered many of the newly arrived migrants from Europe when she undertook the teaching of English at the Bonegilla camp in Victoria. Later still, she had a stint teaching at Port Vila, in what was then the New Hebrides. Back in Australia, she frequently billeted visiting Asian and Pacific students at her flat in St Kilda. In her final decade, a whole new generation of younger gay and lesbian friends interviewed and filmed her, published her stories, helped her write her memoir – and took her to their bars and theatre.

When she died at the age of 106, Monte had lived through a century of huge change. Tessa Morris-Suzuki, the renowned Asian historian, skilfully links her biography to local and global events, as well as taking on the usual biographer’s task of narrating her subject’s life. As she puts it, ‘following Monte’s idiosyncratic footsteps, we find windows opening onto many aspects of Australian society that were long concealed’, such as baby farms, children’s theatrical troupes, private drag parties of 1930s queer society, wartime internment camps, and so on. There are times when this social and political history, however engagingly narrated, tends to obscure Monte’s life trajectory – and with such an extraordinary life, it seems a shame to lose sight of Monte.

Morris-Suzuki entitles her final chapter ‘Unafraid to Be’, and it is exactly this quality in Monte Punshon that the biography brings out so well – a woman who said of herself, ‘I have struggled very often not to be afraid, constantly’, and who chose to ‘treat fear as the spur to go beyond, to explore’.

Comments powered by CComment