- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Importing past enemies

- Article Subtitle: How Australia embraced the fascists it had fought

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

This important and arresting book chronicles the way in which Australia, from 1947 to 1952, imported some 170,000 displaced persons from Europe, a reasonable number of whom were fascists. The striking thing that Jayne Persian (a historian at the University of Southern Queensland) lays bare is the insouciance with which this policy was adopted and the way in which all political parties fell over themselves with enthusiasm for it, though all the main actors were well aware of the influence of fascism among this cohort.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Robin Prior reviews ‘Fascists in Exile: Post-war displaced persons in Australia’ by Jayne Persian

- Book 1 Title: Fascists in Exile

- Book 1 Subtitle: Post-war displaced persons in Australia

- Book 1 Biblio: Routledge, $77.99 pb, 192 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Supposedly, the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA), which later morphed into the International Refugee Organisation (IRO), screened applicants who wished to resettle in Australia for undesirable attributes such as involvement in war crimes and an association with fascist or Nazi groups. In fact, these agencies did no such thing, partly because of the immense numbers to be dealt with. What is startling in this account is that the various Australian governments who implemented DP immigration were aware of this lack of screening and didn’t much care.

It needs to be emphasised at this point that Australia had just spent six years fighting fascism in various forms around the globe and that 30,000 Australians had died in the process of freeing the world from this scourge. Yet, as Persian demonstrates, governments of all stripes were prepared to import as many of these past enemies as could be loaded onto ships. One of the reasons for this is starkly brought out in this book. Despite the fact that we were importing war criminals and murderers, these people had one overwhelming attribute – they were white. Thus we have Arthur Calwell waxing lyrical about Latvians. He had seen some ‘nice blond Latvians’ in a visit to Europe and he was aware that the prime minister, Ben Chifley, ‘liked them blond’. When it was pointed out that some of these men served in the German armed forces (that is, they had fought to further the policies of Adolf Hitler) Calwell stated that nevertheless he preferred the ‘Balts’ over other nationalities, no doubt because they were blond ‘ubermenschen’.

Arthur Calwell in 1940 (National Library of Australia via Wikimedia Commons)

Arthur Calwell in 1940 (National Library of Australia via Wikimedia Commons)

Later, when the Menzies government came to power and it had been revealed that we were harbouring war criminals, the attorney-general (none other than Garfield Barwick) noted that ‘men’ must be able to turn their backs on ‘past bitternesses’. The bitterness he was referring to was of course that produced by the slaughter of Jews and other ‘undesirables’ on the Russian Front. In effect, he declared the chapter on war crimes closed. But as Persian notes, the chapter had never been opened.

Persian also notes that, while the ‘ubermenschen’ arrived in large numbers, one group was excluded. Although some of the DPs were Jews and it was the Jews who had suffered most terribly from the Hitler regime, they were not wanted here. Jews were stated to be ‘not assimilable’, an official of the Immigration Department succinctly summing up government policy by saying ‘we have never wanted these people and we still don’t want them’. At the same time, Calwell was assuring the IRO that ‘we are not anti-Semitic’.

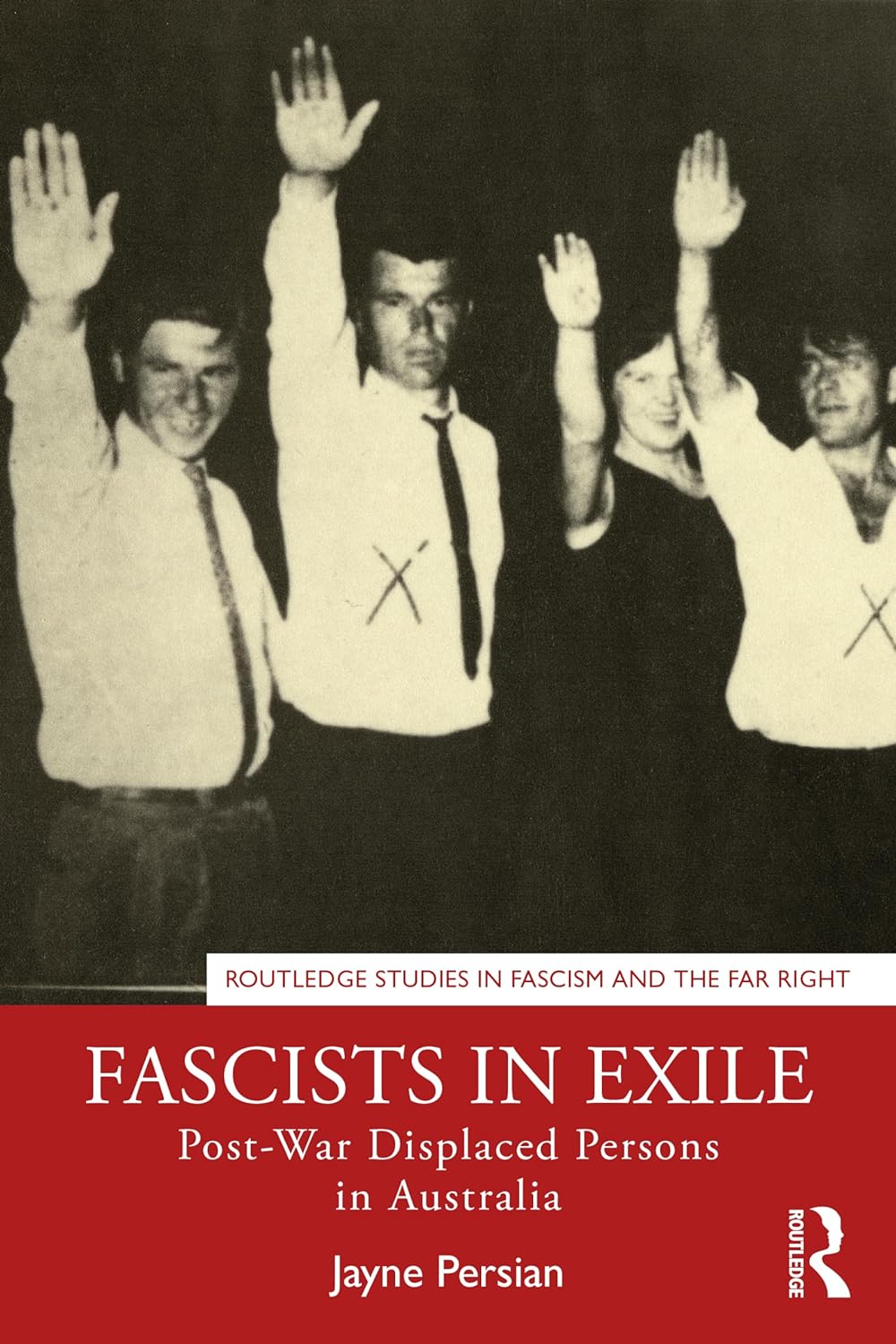

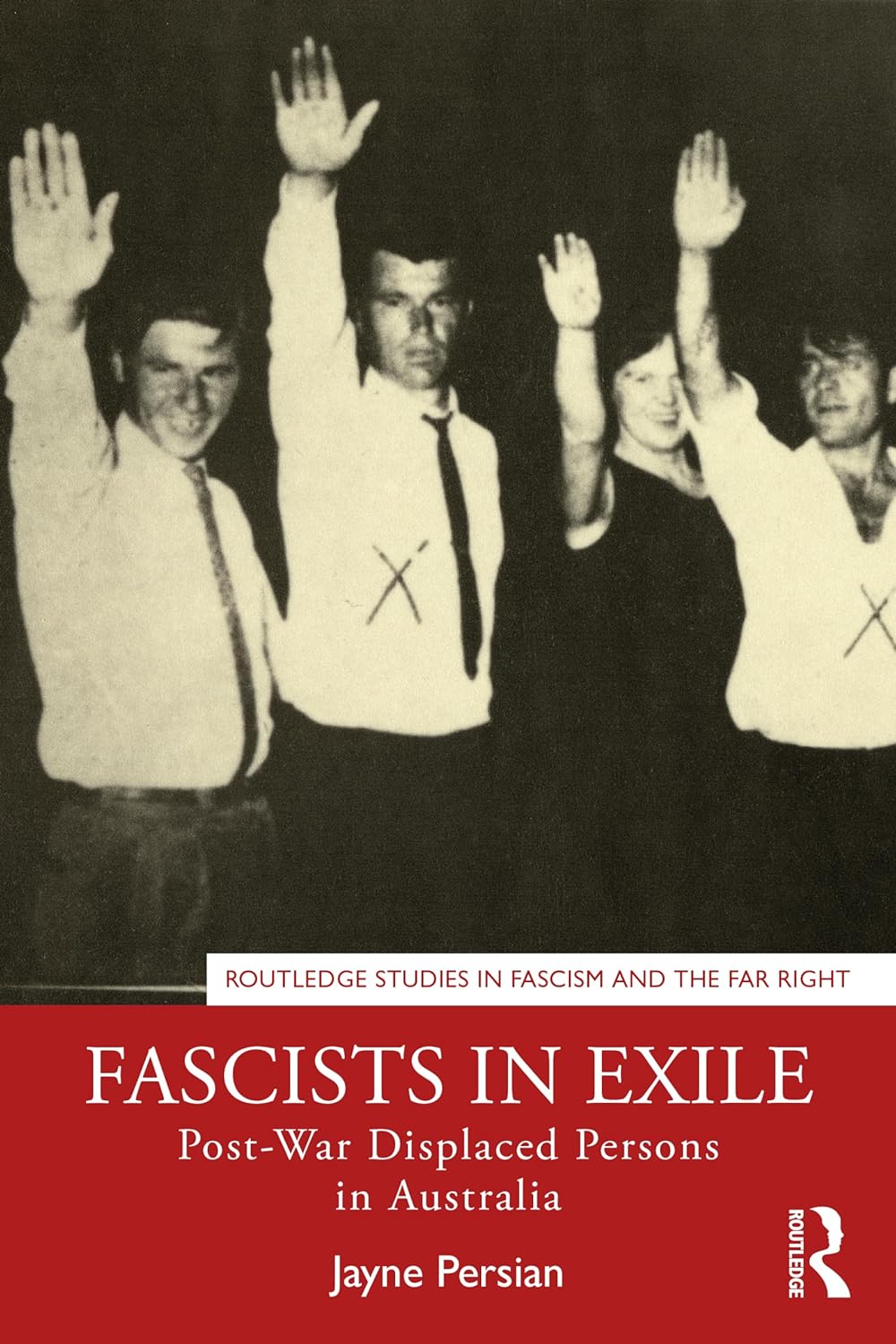

Persian also details what happened to many of these groups when they settled in Australia – in short, they went right on being fascists. The Hungarists (a group of Hungarian exiles) formed associations in most states and greeted each other with the Nazi salute. Their leader in Queensland had in fact worked closely with Adolph Eichmann in deporting Jews to the camps. Notwithstanding this, the group denied the reality of the Holocaust, a fact that did not deter them from running for a Senate seat as late as 1970. This grouping was not alone. Croatian fascists had similar set-ups, as did many others of the so-called ‘captive nations’ of Eastern Europe. It is startling to consider that, as Persian reveals, ASIO was watching these groups but took no action against them. In fact, ASIO recruited Hungarists to inform on suspected communist agents.

This theme runs through the book. In the context of the Cold War, it was not the extreme right that was thought to represent a threat to Australian security, but the communists. The overwhelming concern of the organisations set up by the DPs was that they were mainly violently anti-communist. This chimed well with government priorities, William McMahon (as federal treasurer) describing some Ustasha as ‘a good bunch’ with ‘a good cause’ – this cause in part involving Australian citizens of Croatian origin travelling to Yugoslavia to commit acts of sabotage against its government.

These facts were hardly hidden. Persian reveals that details of the activities of various groups were well publicised. Jewish lobby groups pointed out that Australia had become a safe haven where they continued their fascist activities and regrouped in the hope of better things to come in their real homes in Eastern Europe. It is lamentable, though hardly surprising, that calls for action against fascist groups were ignored by governments of all persuasions.

The tide turned in the 1980s. Bob Hawke, as a friend of Israel, was moved to action when various reports of war criminals came to his attention. A special Investigations Unit was set up and three criminal prosecutions undertaken. In some ways, it was too late. Eyewitness testimony, on which most prosecutions relied, was by then thought too precarious after forty or fifty years to use as a basis for conviction. Nevertheless, the trials did something to publicise what had happened and thus at least performed some educative function.

Jayne Persian’s book is of major importance. It brings to light the little-known story of how, after spending six years fighting fascists, we spent almost as long welcoming those same fascists to our shores. That all governments cared more about race than social cohesion is a lesson that we would do well to remember. The book should be read by all those engaged in immigration policy, especially politicians, both those in power and those who aspire to power. It is a shocking story, well chronicled.

Comments powered by CComment