- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: France

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The dry guillotine

- Article Subtitle: A scandal centred on Jewishness

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Jews are central to narratives of the history of modern France. One narrative thread concerns a story of civic emancipation from the time when Jews were first granted equal rights during the French Revolution until the present, when Prime Minister Gabriel Attal is not only France’s youngest postwar prime minister but also, like his predecessor Élisabeth Borne, of Jewish ancestry. The other narrative thread is of continuing anti-Semitism, most obvious in the Vichy government’s active participation in the deportation of Jews during World War II and still evident in the hundreds of anti-Semitic incidents reported in France every year. The Dreyfus Affair is pivotal to both narratives.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Peter McPhee reviews ‘Alfred Dreyfus: The man at the center of the affair’ by Maurice Samuels

- Book 1 Title: Alfred Dreyfus

- Book 1 Subtitle: The man at the center of the affair

- Book 1 Biblio: Yale University Press, US$26 hb, 225 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

At the same time, a series of national economic and political crises and scandals was to make Jews easy targets to explain fin-de-siècle anxieties. Anti-Semitism became a ‘cultural code’ for all those resentful of the rapid changes associated with finance capitalism, mass democracy, and secularisation, voiced, for example, through the rabid prejudice of Édouard Dumont’s newspaper La Libre parole (Free Speech), which sold 200,000 copies daily by 1894. Jewish officers in the army were a favourite target at a time of international and colonial tensions: as a ‘cosmopolitan’ people, where did their loyalties lie?

Personal jealousies within the officer corps – for Dreyfus’s private income from his family’s textile business was twenty times an officer’s salary – did the rest. In October 1894, written evidence of spying was imputed to him on the flimsiest of evidence. He was found guilty of selling military secrets to Germany and deported to Devil’s Island in French Guyana, popularly known as ‘the dry guillotine’, in the words of Victor Hugo.

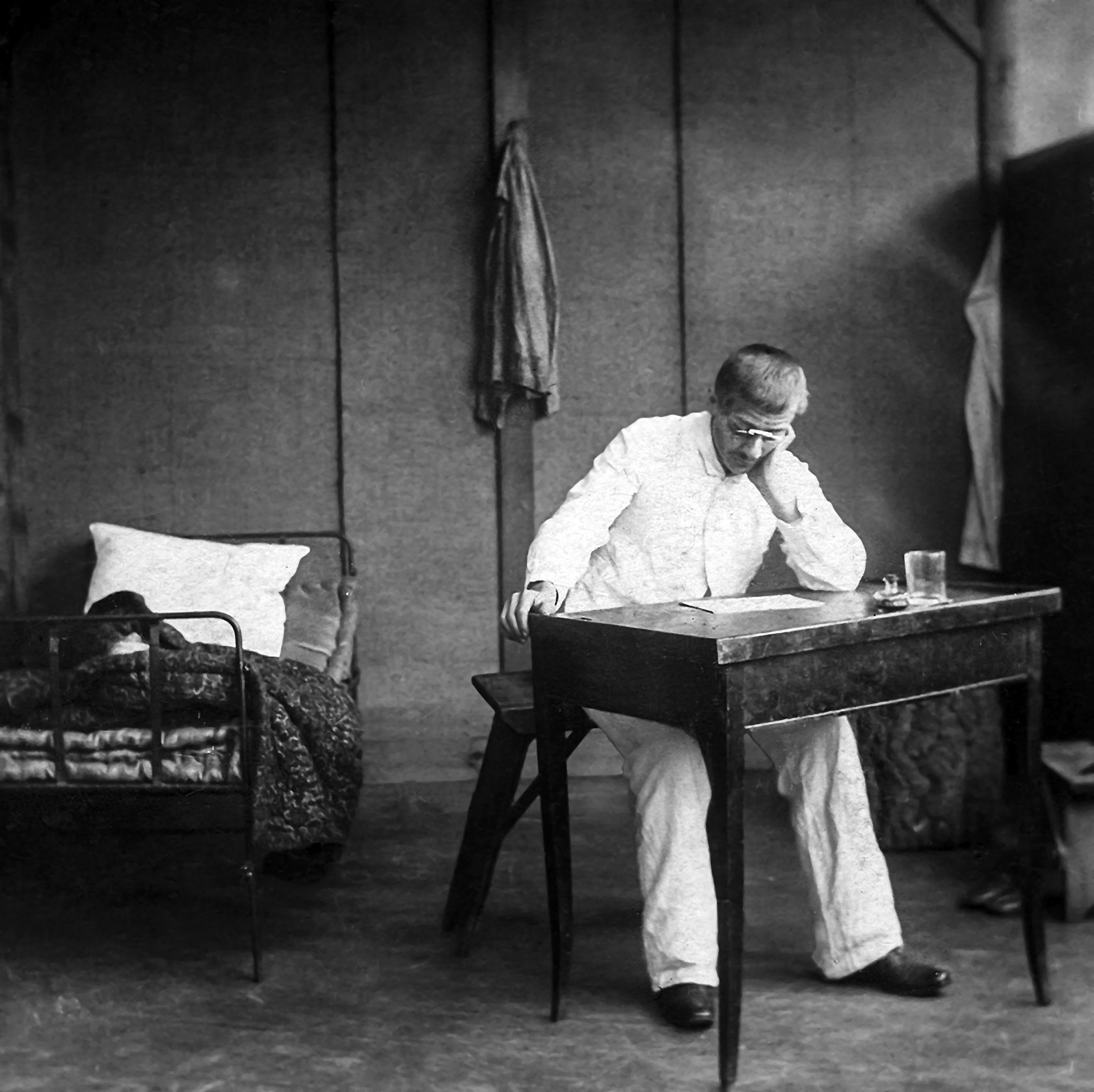

Alfred Dreyfus in captivity on Devil's Island, French Guayana, 1898 (photographer unknown, F. Hame via Wikimedia Commons)

Alfred Dreyfus in captivity on Devil's Island, French Guayana, 1898 (photographer unknown, F. Hame via Wikimedia Commons)

Maurice Samuels’s engrossing biography of Dreyfus includes a harrowing chapter on the deliberate cruelty and chronic illnesses of his four years on the island, softened only by access to books and correspondence with his wife, Lucie. It was an excruciating punishment, but Dreyfus’s plight initially aroused little interest or sympathy in many parts of France, even among most Jews.

In August 1896, a diligent officer scrutinised further handwriting to conclude that the real author of the incriminating document was another officer, named Ferdinand Walsin Esterhazy. This was a breakthrough in the campaign of the small, dedicated band of Dreyfus’s defenders led by Lucie and Alfred’s brother Mathieu. Émile Zola’s open letter J’accuse, attacking the array of Dreyfus’s persecutors in January 1898, sold 300,000 copies of the newspaper in which it was published. Zola’s letter provoked anti-Semitic riots and demonstrations across the country, and in the 1898 elections twenty-two openly anti-Semitic deputies were elected. The anti-Semitic rhetoric anticipated Nazism in its vitriolic violence, especially in Paris, which housed sixty per cent of the 80,000 French Jews.

Not until 1899 was Dreyfus repatriated in order to be retried. A military court still refused to declare him innocent. By then, the Dreyfus Affair had become an issue of the reputation of the French officer corps. Ultimately, international outrage and threatened boycotts of the great Paris Exhibition of 1900 pushed President Émile François Loubet to officially pardon him, but not until 1906 was Dreyfus formally declared innocent and reintegrated into the French army.

The Dreyfus Affair, one of the turning points in modern French history, arrayed anti-clericals and civil libertarians against a powerful coalition of nationalists, practising Catholics, and almost all of the media. But it bitterly divided families, the left, artists, and writers: Marcel Proust followed his mother’s Jewish family in their support for Dreyfus, while his Catholic father backed the army. At the same time as Zola’s letter, a ‘Manifesto of the Intellectuals’ (including Proust, Monet, Pissarro, and Durkheim) marked the moment when ‘intellectual’ came to mean a progressive, engagé figure. But they were opposed by prominent figures on the right: Valéry, Verne, Degas, Cézanne, and Rodin.

The discrediting of the anti-Dreyfusards included the Catholic Church hierarchy, whose newspaper La Croix had reacted to the Dreyfus Affair by insisting (and amply demonstrating) that it was ‘France’s most anti-Jewish newspaper’. It sold as many as 170,000 copies per day. The Dreyfus Affair facilitated the targeting of the Church by successive leftist governments, culminating in the formal separation of Church and State in 1905.

Astonishingly, such was Dreyfus’s commitment to the ideals of republican France that, despite his degradation at the hands of its army, and the death of family and friends in World War I, he enlisted and served in the artillery throughout the war. Maurice Samuels contests the common assumption that this reflects the depth of Dreyfus’s ‘assimilation’. Instead, he argues that Dreyfus personified a model of Jewish identity which melded French citizenship and Jewish culture. Fittingly, his funeral was held on Bastille Day, 1935. He was thus spared the horrors of the Nazi occupation after 1940; Lucie, on the other hand, sheltered under a false name in a Catholic convent before her death in 1945.

Dreyfus was not a practising Jew, nor did he speak often of his Jewish identity. He had absorbed the secular nationalism of the French Revolution: that religion was a purely private matter and that all ethnicities were now subsumed into French citizenship. But everyone knew that that his identity was at the heart of the affair. From the outset, he claimed that ‘my only crime is to have been born a Jew’.

Samuels’s biography lacks the substance and contextual breadth of Michael Burns’s Dreyfus: A family affair, from the French Revolution to the Holocaust (1992), which also emphasised the centrality of Jewishness to the scandal. Unlike Burns, however, Samuels uses Jewish newspapers in French, English, German, Yiddish, and Hebrew to demonstrate the profound resonance of the Dreyfus Affair for Jews around the world. Echoing Hannah Arendt, Samuels sees the despair of French Jews as a crucial turning point in support for Zionism, while for others the eventual triumph of the cause reinforced their faith in national integration. This is the most important conclusion of Samuels’s biography.

The book, which is part of the Yale Jewish Lives series, bears the imprint of our times. Samuels is a Professor of French at Yale University and directs the Yale Program for the Study of Antisemitism. He and others have used the book to make explicit connections between the treatment of Dreyfus and contemporary anti-Semitism. Since its publication, he has commented on what he sees as increasing anti-Semitism on US campuses during the war in Gaza. ‘As antisemitism and right-wing nationalism stage a comeback around the world today,’ he comments, ‘the affair has much to tell us not only about the causes of hatred, but also about the ways it can be resisted.’ So the affair matters, in his words, ‘now more than ever’.

Comments powered by CComment