- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: A curious cinéaste

- Article Subtitle: The enigma of Werner Herzog

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Werner Herzog is perhaps the only cinéaste from the epoch sometimes referred to as the ‘golden age of art cinema’ whose reputation as a pop cultural figure eclipses that of his films. One of the key members of the New German Cinema movement, and the director of celebrated feature films such as Aguirre, the Wrath of God (1972) and The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser (1974), Herzog has come to be known among internet users for his drawling Bavarian accent and his existential musings about solitude, despair, and the brutality of nature. However, as Herzog’s new memoir, Every Man for Himself and God Against All (translated by Michael Hofmann) reveals, behind this ironically morose façade lies a sentimental and deeply thoughtful man who is endlessly fascinated by the human soul and the superhuman drive to transcend what we thought possible.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Corey Cribb reviews ‘Every Man for Himself and God Against All’ by Werner Herzog, translated by Michael Hofmann

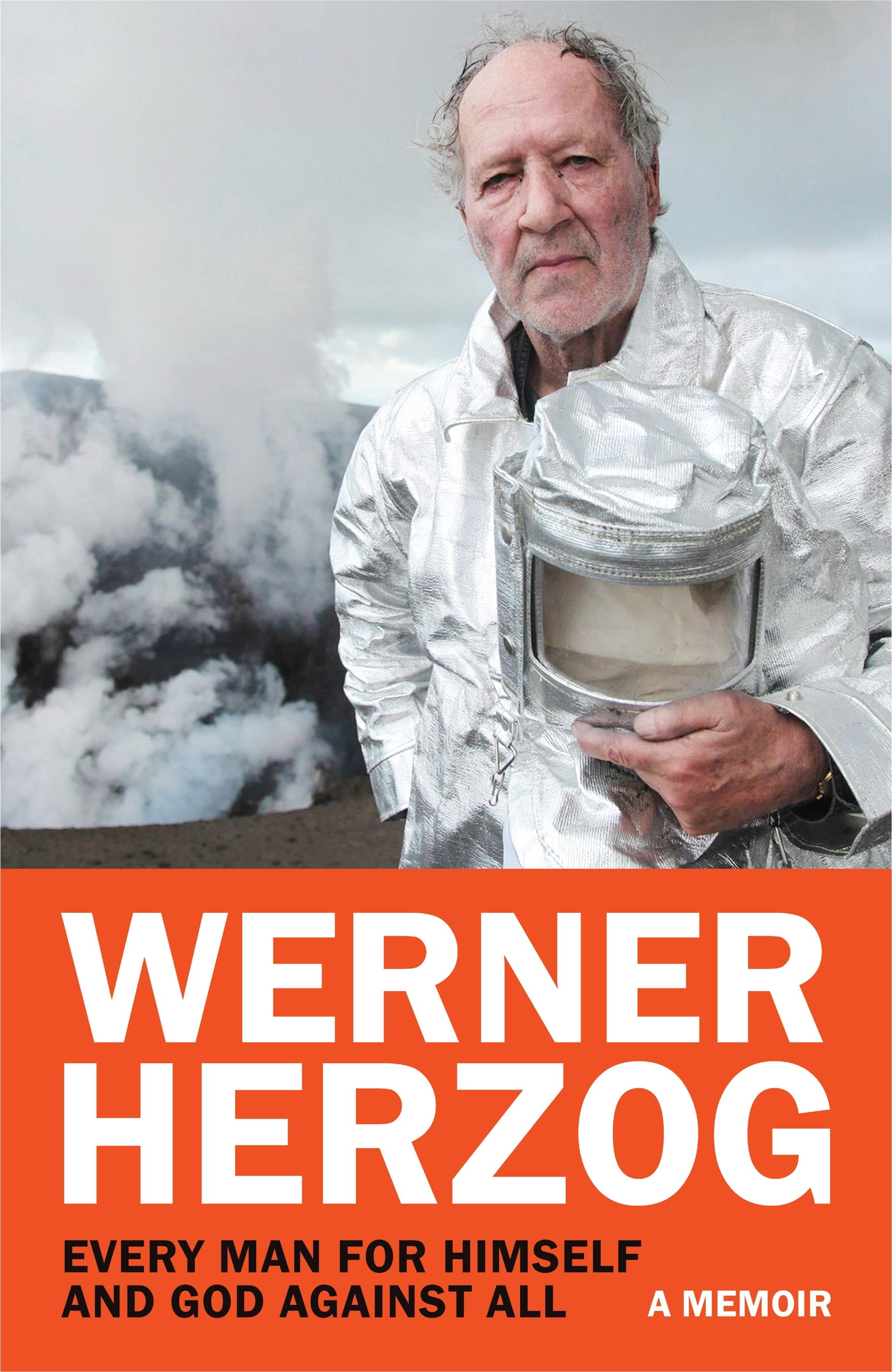

- Book 1 Title: Every Man for Himself and God Against All

- Book 1 Biblio: Bodley Head, $49.99 hb, 355 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.readings.com.au/product/9781529923865/every-man-for-himself-and-god-against-all--werner-herzog--2024--9781529923865#rac:jokjjzr6ly9m

Like Steiner, Herzog’s own life is characterised by improbable acts of profound stupidity, or profound imagination – depending on how you look it at it. In 1972, Herzog walked for twenty-two days from Munich to Paris in the conviction that only his footslog could spare the life of his dying friend Lotte Eisner. Eight years later, Herzog consumed his own shoe on camera after unsuccessfully betting that Errol Morris would never complete his documentary film Gates of Heaven (1983). Most infamously, as documented in Les Blank’s The Burden of Dreams (1982), when directing Fitzcarraldo (1982) Herzog demanded that his cast actually drag a 320-ton steamship over a 100-metre hill when recreating the exploits of the Peruvian rubber baron Carlos Fermín Fitzcarrald. These feats, revisited in Every Man for Himself and God Against All, are as much part of the mythology of Werner Herzog as his films, a mythology to which Herzog’s book adds both style and substance.

As the conventions of the genre dictate, Herzog’s memoir covers his family, his life, his work, the places he’s been and the people he’s known. However, there is a sense that, in spite of his many artistic and worldly accomplishments, Herzog does not view himself as the protagonist of his own story. While the book is vaguely chronological in structure, it is filled with many fabulous digressions and amusing anecdotes that, more often than not, speak to the existence of people who might, in cinematic terms, be described as extras. This is not to say that Herzog is lacking in pride or ego, but that his natural inclination is to assume the role of the story’s chronicler, not its subject.

The first eighteen of the book’s thirty-six chapters are largely dedicated to Herzog’s genealogy, youth, and adolescence, whose misadventures help explain the formation of his eccentric character. Herzog was born into poverty, in a small village named Sachrang, nestled among the German Alps. His well-educated parents were early supporters of the Nazi Party. By the age of fourteen, Herzog had witnessed the bombing of the German town of Rosenheim by Allied forces, engaged in petty crime, and converted to Catholicism. Driven by what Herzog describes, upon seeing Rosenheim in flames, as a curiosity to know the world, before directing his first feature film, Signs of Life (1968), at twenty-six years of age, he spent several years living in the United States, where he studied filmmaking and occasionally entered rodeo competitions for money.

The book’s second half is predominantly focused on Herzog’s filmmaking career and the many precarious, and sometimes dangerous, situations into which his unrelenting vision for cinema led him. During the production of Fitzcarraldo, for example, Herzog and his crew camped in a remote department of Bolivia, far from the nearest settlement, which resulted in several fatalities and serious injuries. When shooting Scream of Stone (1991), Herzog and two crew members were stranded on a mountain during a snowstorm for more than forty-eight hours. His cameraman, ‘a tough and experienced climber’, was fortunate to survive the incident. Even more sensational than this brush with death are Herzog’s tales of ‘the maniacal wild man Klaus Kinski’: the star of five of Herzog’s most acclaimed films, with whom he maintained a famously tense, yet productive friendship, underscored by the occasional exchange of death threats.

Every Man for Himself and God Against All effortlessly glides between personal meditations, character portraits, production histories, and descriptions of the historical incidents which inspired them. Herzog’s memoir is a book that will supply even the most seasoned of Herzog enthusiasts with new insights and oddities and should compel the uninitiated to investigate his oeuvre. As the book attests, Herzog’s persona is more complex than the self-parodic statements that have authorised his status as a meme effect convey. Herzog is a man who has lived, reflected, and created, and his book artfully documents these achievements, without hyperbole or conceit.

Comments powered by CComment