- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Music

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Lady Be Good!

- Article Subtitle: A deep scholarly dive into the singer’s life

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

My one-woman show A Star Is Torn was a sung catalogue of the great women singers who had ‘taught’ me via their recordings. Having assembled a list of twelve, Bessie Smith and Billie Holiday among them, I realised that they had all died young. The original draft also included a bunch of survivors, including Lena Horne and Ella Fitzgerald. My assessment of Ella was based on scant information. When I premièred that show in 1979, she was in her sixties and still touring the world at a phenomenal pace. The rest was largely mythology. Judith Tick’s mammoth biography is authoritative enough to make me believe I now have something much closer to the truth.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Robyn Archer reviews ‘Becoming Ella Fitzgerald: The jazz singer who transformed American song’ by Judith Tick

- Book 1 Title: Becoming Ella Fitzgerald

- Book 1 Subtitle: The jazz singer who transformed American song

- Book 1 Biblio: W.W. Norton & Company, US$40 hb, 582 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

In her acknowledgments, the author refers to a promise she made to Ella’s adopted son, Ray Brown Jr: ‘to take a deep scholarly dive into her life’. The 127 pages of thanks, notes, bibliography, and index attest to the seriousness, and success, of Tick’s academic endeavour. The subtitle offers a clue as to her intent: ‘the jazz singer who transformed American song’.

Becoming Ella Fitzgerald is mainly about the music. Right from the start, the language is less colourful than we might expect from someone who clearly adored Ella. At thirteen, Tick had memorised her Cole Porter Songbook; a few years later, she was buying sheet music of Ella’s songs. If her writing style seems less passionate than we might expect from a fan, her musical authority sets this biography apart. One of its greatest joys is the way her detailed musical analysis of the vocal and instrumental approach to particular tracks – ‘Oh, Lady Be Good!’ – for instance, drives us to listen to the recordings themselves. The most mainstream of these are instantly accessible via the internet, but Tick’s own observations are enhanced by her access to private collections and live recordings never publicly released: she believes there will be much more to be written when these surface.

What we get throughout is not only Ella’s own commentary from interviews, television appearances, and live performance, but also the presence of the greats she worked with. Chick Webb, Charlie Parker, Ray Brown, Duke Ellington, Dizzy Gillespie, Count Basie, Joe Pass, and so many more are musically here in her company. So are the journalists, the critics, and the men who often dictated the direction of her long career. For while Ella lived far longer than her contemporaries Billie Holiday, Dinah Washington, and the singer she said she would ‘mentor and make sure to get her straight because this girl is so talented’ – Whitney Houston – Ella’s professional life had much in common with the great vocalists who went under. While Tick’s portrait respects the memory of a woman who valued privacy, a profile emerges of someone initially told she would never make it because she didn’t have good looks, grew to be most happy and supremely powerful when she was in front of an audience, and yet was constantly under pressure from the men who managed her contractual obligations to recording companies and to a ridiculously punishing schedule of live appearances. Ella Fitzgerald remained grateful and loyal.

Tick writes from a feminist perspective, but resists underscoring her commentary with feminist theory. In telling the story date by date, show by show, one hefty recording session after another, the book takes us on a journey from amateur hopeful through vocal risk-taker to international superstar. Managers and record producers continually force her into commercial repertoire, yet there is a parallel woman recognised by her collaborators as knowing exactly what she wants musically. She is almost universally acknowledged by them and most critics as the first singer to use her voice as an improvising jazz instrument. But Tick also even-handedly reports various negatives, including one critic’s accusation of a lack of ‘emotional intelligence’ in Ella’s approach to Cole Porter’s songs: on relistening, I was far less tolerant of this insult.

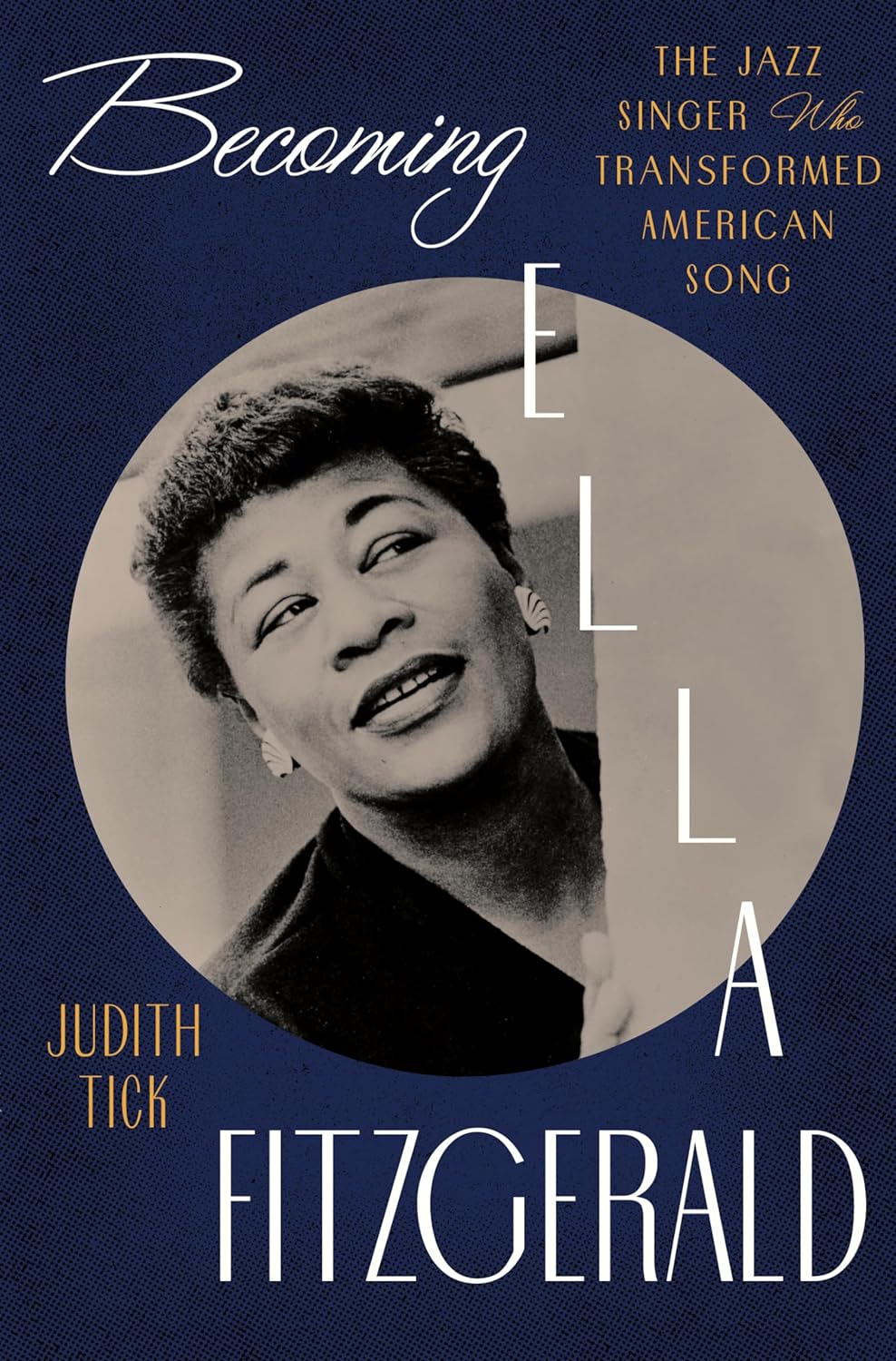

Ella Fitzgerald c.1968 (Pictorial Press Ltd/Alamy)

Ella Fitzgerald c.1968 (Pictorial Press Ltd/Alamy)

On stage and in the bus on the road, she is ‘one of the boys’ and nicknamed Sis, but once the professional obligation is over, she remains in the company of the female assistants she could eventually afford to accompany her, or the female family at home. Her marriage to Ray Brown lasted a few years, but they were often on the road apart, and continued to work together off and on for years after their divorce. While there appear to have been affairs and a number of statements about loneliness, along with the odd speculative interpretation of her rendition of the song ‘A House is Not a Home’ (to which she added ‘without a man’), what appeared to another reviewer to be a plodding account of her later career seems to me to reveal her joy in the unfettered proof of self-worth when in front of an audience, and in the vast sales of her recordings: nothing else mattered as much.

The racist context of Ella’s journey is similarly present and details the societal and cultural apartheid that dominated her early years. Raised from three years old in a tough neighbourhood on the ‘wrong’ side of the river in Yonkers, her hard-working mother and stepfather struggled at times, but managed the luxury of a phonograph, Bessie Smith records, and early piano lessons for their daughter, whose initial ambition was to be a dancer, and whose early schoolyard energies belied later shyness and a constant need for reassurance. Tick makes it subtly clear that Ella’s ‘becoming’ was always in the context of her as a woman, a woman of colour, and a woman whose feisty side emerges here and there. She may have declined overt commentary, but Ella supported the Black Rights movements through fundraising performances and her own philanthropy.

Among the forensic tracing of a career, and its multiple insights, there are also moments of pure entertainment in the book. A reference to the 1963 Dinah Shore television show in which Ella appears alongside Joan Sutherland (singing ‘Three Little Maids’ and ‘Lover Come Back to Me’) prompts an irresistible YouTube search. Ella’s interest in the theme from Neighbours reinforces her ever-present quest for new repertoire. Her response to a cynical Michael Aspel seems typical of her outlook: ‘I liked the song ’cause I felt that’s something that we should all try to be, neighbors, where we share and love each other.’ Unexpectedly moving is Ella’s own account of the night in 1979 she received, along with Henry Fonda, Martha Graham, Tennessee Williams, and Aaron Copland, the Kennedy Centre lifetime achievement honour:

I was crying, and I asked Tennessee Williams – he was sitting beside me – for his handkerchief, and I told him I thought I would just keep it as a souvenir of that night. He said ‘Oh no you don’t. You can’t have that handkerchief. I’m keeping that one for myself because it’s got Ella Fitzgerald’s tears in it.’

In 1967 an East German critic spoke of her ‘vigorous and unsentimental style’. While my enjoyment of this book has much to do with my own taste for the unsentimental and my own special interest in the craft of singing, I think Judith Tick has honoured Ella Fitzgerald in this straightforward and painstaking account of her resilient life and legacy.

Comments powered by CComment