- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Film Studies

- Review Article: Yes

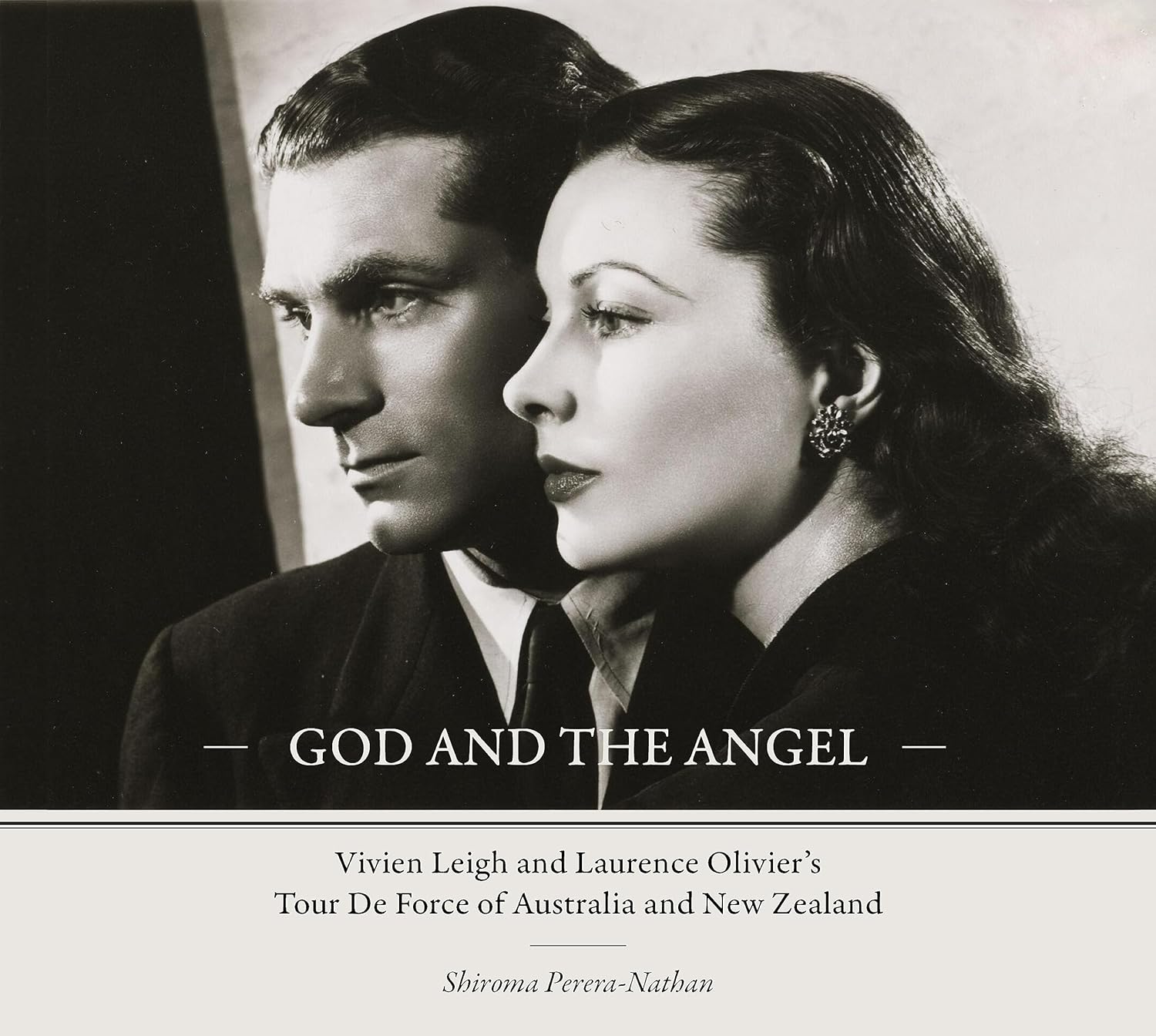

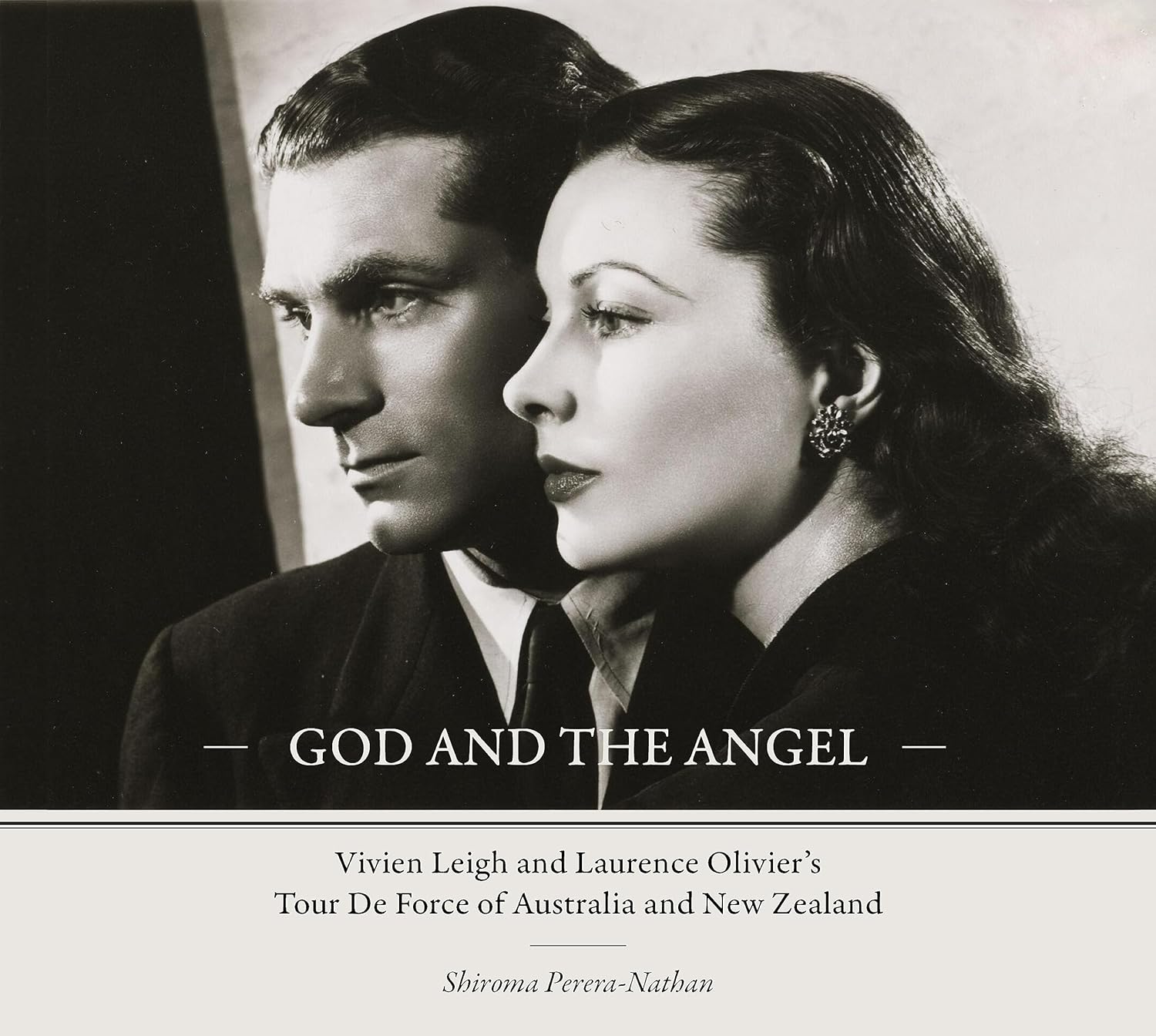

- Article Title: Lacquered in glamour

- Article Subtitle: The Oliviers’ famous tour of 1948

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

This attractive and fascinating volume is billed as ‘the first illustrated book on the 1948 Old Vic tour’, and, sure enough, it is jammed from stage-left to stage-right with scores of images – especially of the eternally photogenic two superstars who led the tour. Not among them is one particular photograph – more of a snapshot, really, just 6 x 4½ inches in 1948 measurements. It was taken on the night of 17 May 1948 at a post-performance party at a family home in Melbourne’s St Kilda. Four of the seven people in shot are unidentified; but two of the others, unmistakably, are Vivien Leigh and her husband, Laurence Olivier: she is in a fur coat, sitting in an armchair, a plate of food balanced on her lap; he is two along, perched on a piano stool. But who is that man in the middle in half profile? None other than Chico Marx, who was also in Melbourne, with his own show at the Tivoli.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Michael Shmith reviews ‘God and the Angel: Vivien Leigh and Laurence Olivier’s tour de force of Australia and New Zealand’ by Shiroma Perera-Nathan

- Book 1 Title: God and the Angel

- Book 1 Subtitle: Vivien Leigh and Laurence Olivier’s tour de force of Australia and New Zealand

- Book 1 Biblio: Melbourne Books, $59.95 hb, 253 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

A disclosure: that photograph, sitting in front of me now, is a family heirloom. The party, at which Chico sat at my late grandfather’s Steinway and performed most of his act, was at my grandmother’s house. On the back of the photo is scrawled an unpunctuated sentence (‘Viv Leigh Chico Marx Laurence Olivier etc 47 Barkly St.’) in the unmistakable loopy hand of my late aunt, Verna. Most important, it was taken by my late father, the Melbourne photographer Athol Shmith, who had more or less become the company’s official snapper.

Many more of Athol’s images, most of which I have never seen, grace the present book, and its author, Shiroma Perera-Nathan, pays him handsome tribute, alongside an informative account of that Barkly Street bash. How I wish I’d been there, too, but I hadn’t been born yet.

As Perera-Nathan suggests, the popularity of the Old Vic’s six-month visit was a harbinger of Queen Elizabeth II’s royal tour six years later. The company’s monarch was Richard III – the Shakespearean one, and one of Olivier’s signature roles. The two other plays in the season were Richard Brinsley Sheridan’s The School for Scandal and Thornton Wilder’s The Skin of our Teeth. The latter, designed as a starring vehicle for Leigh, did not please everyone: one woman lamented to Truth newspaper, ‘You know, if any local outfit tried to put on a crazy play like this, they’d probably be booed out of town.’

As the book reveals, there were complexities, even well before the Old Vic arrived. The Oliviers and around forty members of the company came by sea, on the SS Corinthic. It sailed from Liverpool on St Valentine’s Day and, after a stop in South Africa, docked at Fremantle a month later. There was bouillon served on deck, Black Russian cocktails shaken in the bar, and intensive rehearsals conducted in the ship’s dining room.

From the moment the tour hit Perth, progressing steadily to Adelaide, Melbourne, Brisbane, Sydney and Hobart, thence to New Zealand, the Oliviers were never out of the public eye, onstage or off. As specified by the British Council, which had planned and funded the visit, the latest of its ‘cultural tours’, the two actors had double roles to perform: a daunting juxtaposition of the professional requirements at which they were adept and the public duties which were often beyond their ken. These included countless gubernatorial, parliamentary, mayoral, diplomatic, academic functions; myriad speeches and lectures; more than a few farcically overreaching media conferences (sample question: ‘Tell us, Sir Laurence, now that Britain’s finished, how will the Empire be divided up?’); and sundry visits to a range of war memorials, broadcasting studios, animal sanctuaries, and private homes. All this in addition to their night work, plus Wednesday and Saturday matinées.

Such constant pressure took its toll, and both Leigh and Olivier missed several performances due to exhaustion or injury or, in Leigh’s case, continuing TB-related ailments and bipolar disorder. Also, Olivier was notified, while in Sydney, that his Old Vic contract would not be renewed, along with those of his co-directors Ralph Richardson and John Burrell. All this, and the young Peter Finch hovering in Leigh’s vision.

Despite such obstacles, the tour proved to be an overall success that more than realised the British Council’s intentions to promote Britain’s cultural and educational achievements. Reviews and box office were generally positive, as was public opinion. As one starstruck teenager observed, ‘They were famous, rich, lacquered in glamour and magically skilled.’ The affection was mutual, if not always as eloquently expressed. As Olivier cringingly told his audience at an official lunch in Melbourne, ‘You have all been absolute beauts. And we’ve had a bonzer time here.’

Perera-Nathan assiduously relates the ups and downs of the tour in detail, but there are perhaps too many detours and distractions. For example, do we really need to know so much about the histories of various cities, hotels, and theatres, or that someone’s husband’s cousin was married to an Old Vic actor who was not actually on the tour? Sharper editing would have taken care of several typos, including ‘Saville Rowe’ and ‘Wells’, for Orson Welles.

However, as the author herself says, this book is a labour of love rather than a treatise. It is admirable for its passion, thoroughness, and scholarship in bringing these events of seventy-six years ago into contemporary focus. It would make a damned good Netflix series.

Comments powered by CComment