- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Song worth singing

- Article Subtitle: Omar Sakr’s latest collection

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The title of Omar Sakr’s latest collection references the Covid pandemic and comes from his prose poem ‘Diary of a Non-Essential Worker’. It also reminded me of Plato’s banning of the poets from his ideal republic, and Auden’s line that ‘poetry makes nothing happen’. Throughout Non-Essential Work, Sakr explores the limits of poetry and its function in society, questioning the value of his own art, letting us in on his doubts. In the poem ‘Your People Your Problem’, he asks: ‘What is a song worth singing here? / The silenced are listening.’ Despite these doubts, or perhaps because of them, he has achieved a powerful collection of lyric poetry, simultaneously political and intimate.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Mike Ladd reviews ‘Non-Essential Work’ by Omar Sakr

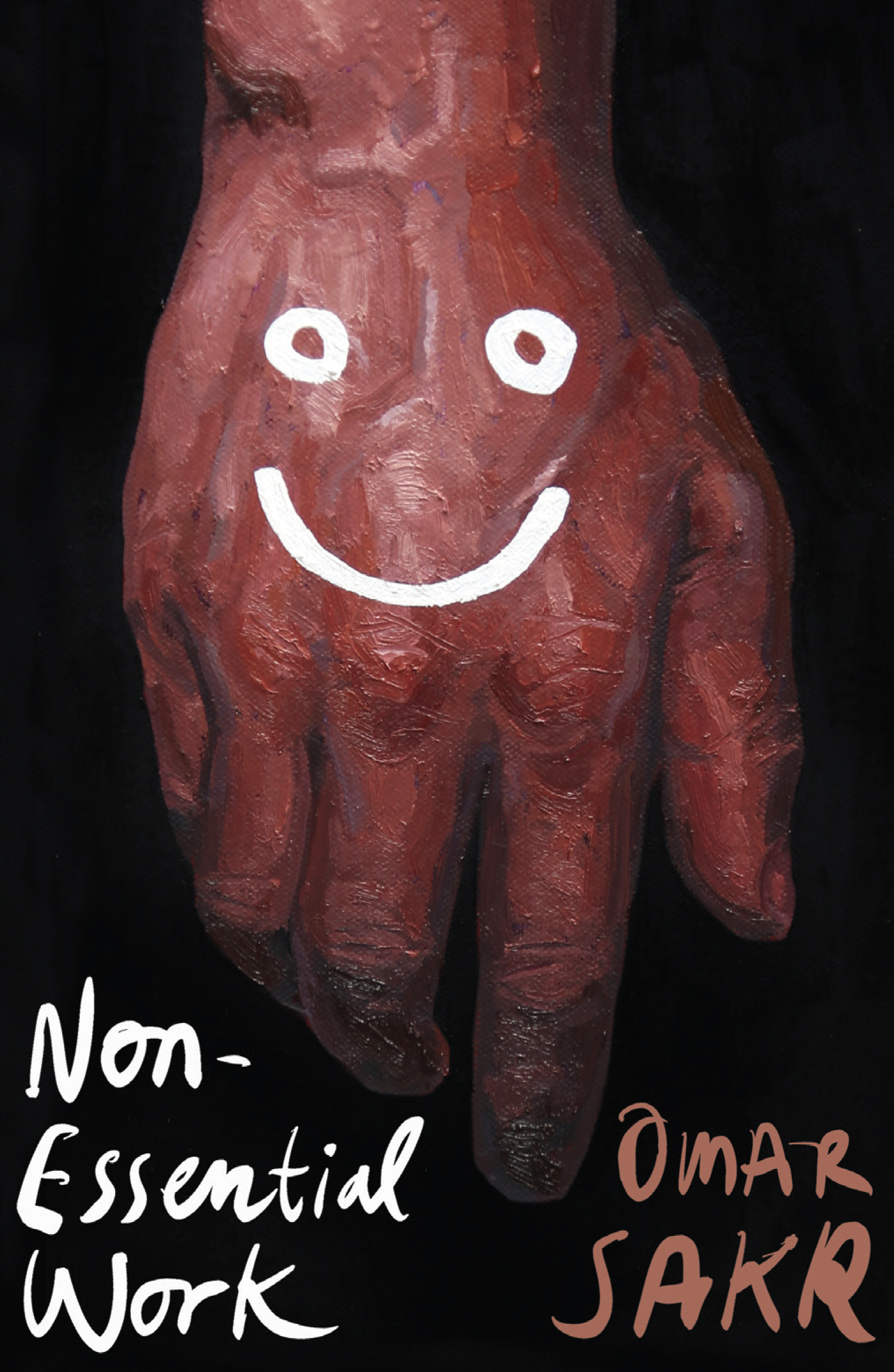

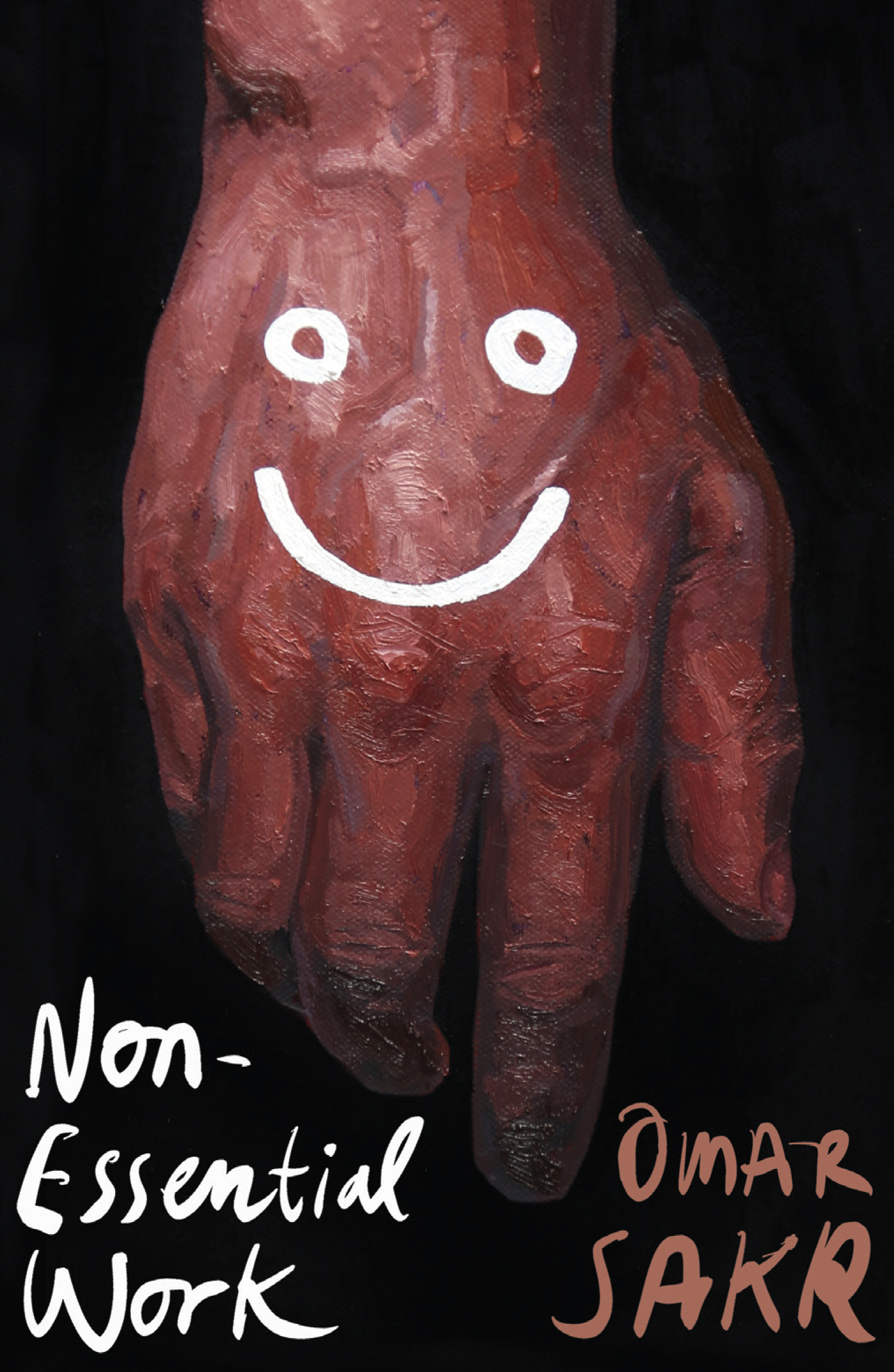

- Book 1 Title: Non-Essential Work

- Book 1 Biblio: University of Queensland Press, $24.99 pb, 116 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

I know Sakr feels his biography is over-quoted when discussing his writing, but it’s relevant here to his double position as a true believer in poetry and questing sceptic. The son of Lebanese and Turkish Muslim migrants, Sakr grew up in Western Sydney. His father left the family early, ‘before I knew him or could speak’. Sakr was brought up by his mother and wider Lebanese family. Poetry was seen as effete and élitist in his world. It didn’t even register with Sakr until he took a poetry elective at university; he had to finish his course, and it seemed like an easy option. The elective was given by poet Judith Beveridge, whose teaching, Sakr acknowledges, changed his life. In the poem ‘Confession’, addressed to his mother, he says:

Immi, I’m sorry I live

for poetry now. This is my excuse.

Your reality is no match for my memory

which comes to me with your face

sneering, where’s the money, where is

the money in a sonnet you idiot.

Sakr’s parents haunt Non-Essential Work. His mother has words like ‘bruising’, ‘wounding’, and ‘unforgiving’ associated with her. She has been damaged by abuse and in turn has inflicted abuse; Sakr’s relationship with her is something he still hopes to ‘unknot’. His father is described as ‘absent’ or ‘a zephyr’ breezing from one place to another. Sakr moves toward him in dreams, but his father is always receding, and now, having died, is radically unreachable.

Almost all the poems operate under pressure in this collection, and not only the pressure of family. In his notes to the poem ‘No Context in a Duplex’, Sakr writes of being sickened by the poem even as he ‘felt its necessity: to show the violence facilitated by language, the violence of metaphor’. In particular, this poem quotes the phrase ‘Mowing the grass’ used by the Israeli military to describe the bombardment of Palestinians. At the same time the poet composes beautiful language, he speaks of massacres in Gaza, the drowning of Alan Kurdi, a three-year-old Syrian refugee child, and oppression of the Uyghurs. His poem ‘After Christchurch’, consisting of the title and a blank page, is a reference to Adorno’s much misquoted statement, ‘To write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric’, a statement that Adorno later retracted. Sakr adds a postscript to his page of silence, ‘What did you imagine there? / Write it down.’ A sequence of poems called ‘On Finding the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) in Dante’s Inferno’ refers to the gruesome Canto XXVIII where Muhammad is confined to the eighth level of Hell and suffers eternal disembowelment, split from chin to colon, for sowing discord and division. In the sequence, Sakr seeks to rescue his Prophet from Dante’s clutches and then to explore his own Muslim faith, sexuality, and concepts of holiness.

Sakr’s poetry is fleshy, lonely, longing, and centred on the body. He details in this and earlier collections such as The Lost Arabs (2019) and his novel Son of Sin (2022) his experience of bisexuality, the rift it caused with his father when they finally met, and the complexities of being bisexual while maintaining his faith and living in a Muslim community. Another layer in Non-Essential Work is that Sakr is now married to a woman and he and his wife are expecting a child (who has since arrived). This gives rise to some wonderful poems, particularly ‘An Ode to my Future Son’. The lyric ‘I’ (once deconstructed by postmodernism) is front and centre in Sakr’s poetry with its first-person narrator, whose thoughts and moods we are asked to share, and private worlds opened to the public.

Sakr speaks Arabic but is not literate in it, and he does not acknowledge any influence from traditional Arabic poetry. Nevertheless, I notice certain affinities in his writing to the ghazal. He sometimes plays with its couplet form and its refrain lines using rhyme and half-rhyme, internal or enjambed, but I think more importantly there is a connection to the traditional subject matter of the ghazal: love and the pain of separation from love. He also uses the trope of the poet symbolised as bird, admittedly a trope that extends much more broadly than Arabic poetry. In Non-Essential Work, Sakr also borrows (with acknowledgment) a form invented by American poet Jericho Brown. Known as ‘The Duplex’, it combines elements of the ghazal, the sonnet, and the blues. Sakr also uses a form created by Egyptian-born poet Marwa Helal, who now lives in Brooklyn, New York. Called ‘The Arabic’, it is a poem written in English that makes only accidental sense when read from left to right, but when read in the opposite direction, as in Arabic, the meaning becomes clear. Try this excerpt for yourself from his poem ‘Believe’:

beliefs, sorry – lies my all put I

and language in

my those are these

:alone left dog

.for living worth is love

.for dying worth is Love

It is a credo for Sakr, who says in his notes to Non-Essential Work that literature for him ‘is the province of elegy – and love. More than anything else, I hope my love has shown through.’

Comments powered by CComment