- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The bird’s head

- Article Subtitle: Prose that makes eye contact

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

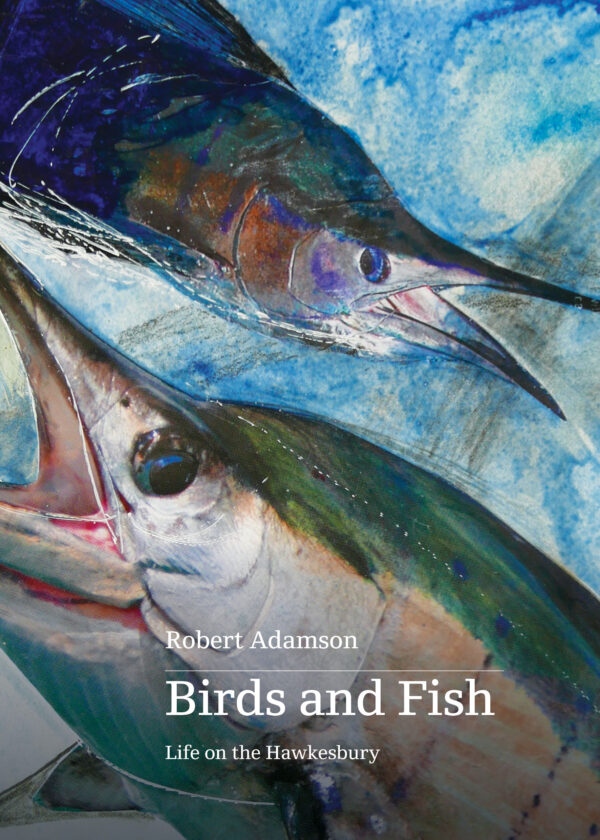

In the year leading up to his death, the poet Robert Adamson (1943-2022) gathered together a selection of his work that focused on one of his enduring passions: the birds and fish of the Hawkesbury River, beside which Adamson lived much of his life. Adamson was best known for exploring this passion in poetry, but the pieces collected in this new book are works of prose and include selections from Adamson’s autobiography Inside Out (2004), and from his late collection, Net Needle (2015). They also include material that is likely to be less familiar to readers, pieces published in the magazine Fishing World, and extracts from a journal Adamson kept between 2015 and 2018 titled ‘The Spinoza Journal’.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Simon West reviews ‘Birds and Fish: Life on the Hawkesbury’ by Robert Adamson and edited by Devin Johnston

- Book 1 Title: Birds and Fish

- Book 1 Subtitle: Life on the Hawkesbury

- Book 1 Biblio: Upswell, $29.99 pb, 117 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

The first writings included describe Adamson’s boyhood fascination with capturing birds and bringing them home to live with him in makeshift cages. This interest, beginning with pigeons, lorikeets, and finches caught in the wild, quickly becomes an obsession, and leads to a number of nocturnal adventures stealing birds firstly from local breeders, and finally even a riflebird from the Taronga Zoo. Where does this childhood fascination with animals come from? It is a passion described by many poets who have grown up close to the natural world. I think for example of Ted Hughes, but also of writers such as Henry Williamson and Gerald Durrell. Adamson describes how the birds would

always bite my fingers. I sustained a few serious wounds and some became badly infected, but still it was contact, and that was what I wanted. It excited me. I wanted to will myself into the bird’s head – not to tame it exactly. What I think I was hoping for when I stared into each bird’s eyes was some flicker of recognition, some sign of connection between us.

Making eye contact with the birds and fish Adamson captures or keeps is a key moment in many of the encounters described in this book. There is something strange and confronting about meeting the gaze of a creature that is not human. The animal is so far from our understanding of ourselves, and yet, like us, is alive and conscious of the world around it. That moment of mutual recognition is elating, but also destabilising, because it poses questions about our own being in the world. As Gerard Manley Hopkins wrote, ‘What you look hard at seems to look hard at you.’ Adamson writes interestingly of the ambiguity of the catch. That desire to be close to the animal, to will himself ‘into the bird’s head’, must also come to terms with the cage and the curbing of the animal’s wildness. As William Blake says, ‘A Robin Red breast in a Cage / Puts all of Heaven in a Rage.’ As a result of his night-time raids, it is Adamson himself who, still a boy, ends up in trouble with the police and behind bars. Those familiar with Inside Out will remember how tragic this turn of events was in Adamson’s life, but this new book keeps its focus on the joys of encounters with wildness.

I like the way these early stories of theft come full circle at the end of Adamson’s life, as he contemplates donating a rescued bowerbird chick, which he nurtured and raised for four years, to Taronga Zoo. Charting his relationship with Spinoza, as he names the bird, is the subject of ‘The Spinoza Journal’. Relationship seems to be the right word here, because ‘Spin’ quickly becomes a part of the family. He develops a personality, and seems to be as curious about his captor as Adamson is about him. He flies freely about the house and enjoys play-dates Adamson devises with other wild birds by placing Spin, in his cage, on the lawn surrounded by plates of food. Adamson writes, ‘I sense an empathy between us’, and goes on:

I notice Spin’s tail feathers are sometimes split at the tips – like a bird’s version of split ends. The feathers are remarkable resilient. When Spin is not in top form – when he is unwell – his tail and wingtips fray and split apart. Then after he has a bath and sits in the shady sunshine for a couple of days, the feathers interlock again and shine with tone.

Adamson likes to focus on such details in his record of their interactions, as if the nurturing of Spin resembles the devotion of prayer or enacts a philosophy of merging oneself with the natural world. Of fishing, for example, he says: ‘I discovered that to repeatedly catch good mulloway I had to try to become part of the river system itself.’ Readers familiar with Adamson’s poetry will recognise these ideas. In the poem ‘On not seeing Paul Cézanne’, for example, he writes,

Everything that matters comes together

slowly, the hard way, with the immense and tiny details,

all the infinite touches, put down onto nothing

The hard way is the way we, as humans, must come to understand our place in the world, and both our similarities to and differences from the creatures of the natural world. Birds and Fish: Life on the Hawkesbury charts this process over a lifetime and is a fine accompaniment to Adamson’s poetry.

Comments powered by CComment