- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Music

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: From the new world

- Article Subtitle: Musical activist and cultural agent

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Louise Berta Mosson Dyer (née Smith; later Hanson-Dyer; hereafter, Louise) lived several lives. An eccentric Melbourne socialite, married into the money of Linoleum King, Jimmy Dyer, she moved on from the expectations of provincial charitable good works in her mid-forties to found a ground-breaking new publishing house in Paris. Les Éditions de l’Oiseau-Lyre, or the Lyrebird Press, pioneered innovative, daring editions – of music, books, and later, recordings – sometimes at the cutting edge of technology.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Malcolm Gillies reviews ‘Pursuit of the New: Louise Hanson-Dyer, publisher and collector’ edited by Kerry Murphy and Jennifer Hill

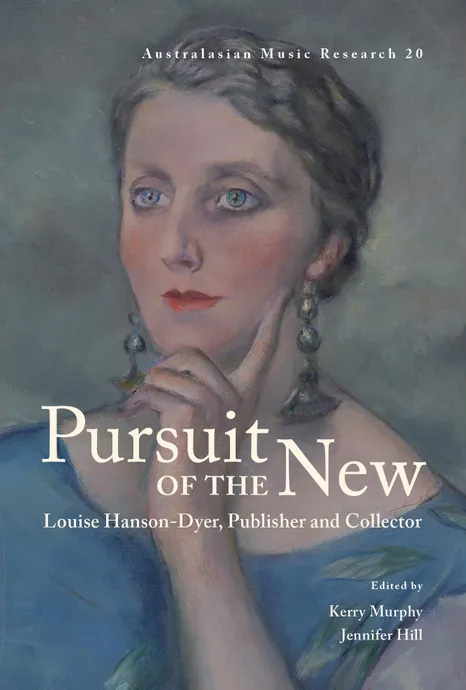

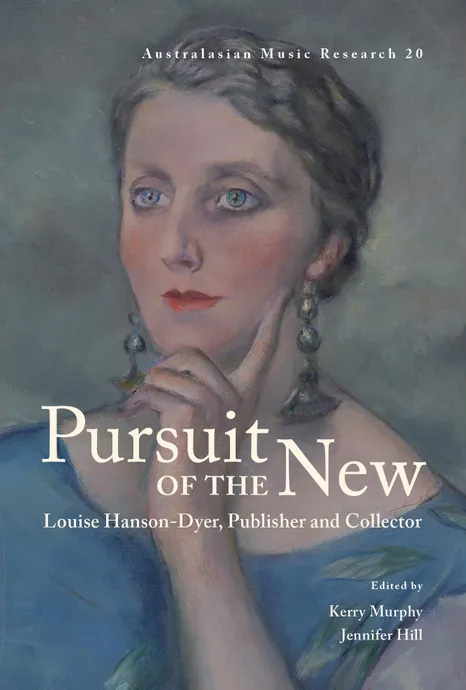

- Book 1 Title: Pursuit of the New

- Book 1 Subtitle: Louise Hanson-Dyer, publisher and collector

- Book 1 Biblio: Lyrebird Press, $55 pb, 283 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

More interested in effective spending, rather than earning, of money, she harboured an aim of always producing, beautiful deluxe publications, with novel bindings, covers or record sleeves, for which she won a Grand Prix des Beaux-Arts for quality design and printing at the 1937 Paris Exposition. Her managerial abilities in marshalling musicological and performing expertise behind her forays into early, baroque, and contemporary music were most astonishingly seen in the eighteen-month schedule she set herself for the production of a twelve-volume edition of François Couperin’s music. And she delivered that complete edition in time for the bicentennial commemoration of the composer’s death in 1933. The French president, Albert Lebrun, attended its launch in support of this unexpected ‘non-French, female, and from the new world’ champion of a French musical icon.

Despite her thirty-five years of European residence, Louise still called Australia home, with the University of Melbourne becoming a major beneficiary of her will. Even the eponymous lyrebird finally started its flight back home, after completing its last European sorties, some twenty years ago. Pursuit of the New is the seventeenth volume in Lyrebird Press’s Australian phase, all volumes of which are devoted to themes concerning Australasian music and musicians.

Somehow Australia, even its musicians, forgot about Louise, until Melbourne historian Jim Davidson produced his detailed yet delicious Lyrebird Rising in 1994 (reviewed by Thomas Shapcott in the May 1994 issue of ABR). Davidson presents her as a New World ‘cultural revenant’, with ‘a polymath’s thirst for knowledge combined with a dash of intellectual buccaneering’. Moreover, he looked upon Louise as having ‘a perfect formula for female independence’, through her two intergenerational marriages. For Jimmy Dyer, a musical enthusiast, was a quarter century her senior, while her second husband, the musician and linguist Jeff Hanson, was a quarter century her junior. Mind you, among musicians this is not so unusual. Perhaps the Hungarian composer Zoltán Kodály was the ne plus ultra, with a rich first wife old enough to be his mother, and a second wife young enough to be his great-granddaughter. Louise, then, comes across in Davidson’s account as a self-confident patroness who refines her roles of cultural agent and musical activist through her mid-career translation to the larger canvas of France and then, after spending the war years in Oxford, soon deciding to base her enterprises in Monaco. The title of his biography’s third part, ‘Herself At Last’, devoted to her pre-war decade in Paris, perhaps says it all.

In editing Pursuit of the New, musicologist Kerry Murphy and rare-music curator Jennifer Hill, have wisely not sought to duplicate or update Davidson’s ‘lynchpin’ biography. They have concentrated upon Louise’s role as an innovative publisher of ‘monumental editions’ and a substantial collector, particularly of visual art works. Their book’s chapters evolved from a two-day symposium in 2018, in Melbourne, at which much new research about Louise’s Press was presented. This circumstance arose from the final consolidation of the Lyrebird archives at the University of Melbourne, affording access to information about its business operations, its correspondence files, and the brilliant designs of its many publications. Pursuit of the New is, however, also noteworthy because of its presentation of once-forgotten Louise as a model of ‘women’s work in music’ of its time. Indeed, she now has her own chapter, as a ‘Patroness of Music Publishing’, authored by Elina G. Hamilton, in The Routledge Handbook of Women’s Work in Music (2022). Louise stands tall among peers such as the founder of the Cleveland Orchestra, Adella Prentiss Hughes, or, perhaps more closely, Francophile founder of New York’s Society of the Friends of Music, Harriet Lanier.

Pursuit of the New’s dozen chapters were written by a network of mainly Australian, French, and British scholars, ‘united in their admiration of Louise Hanson-Dyer’. Occasionally, both in what is said, or what they avoid saying, there is a whiff of hagiography around the representation of this Melbourne PLC Old Girl turned international patroness-publisher, only strengthened by the fact that the book’s publisher is essentially the book’s subject. What is most impressive about this heavily footnoted volume, however, is the way in which these newly available documentary sources, as well as countless other now-published sources from Louise’s contemporaries, have been woven into major contributions to music and art histories, performance and recording practice, and the understanding of French artistic life during the Depression.

The most substantial infusion of new perspectives post-Davidson comes in the volume’s three chapters written by Gerard Vaughan, former Director of the National Gallery of Victoria: about Louise’s early Melbourne connections with the visual arts; her work as an intensive collector of visual art works, mainly during her first half-dozen years in Paris; and her longer-term proselytising for French modernist art in general. Particularly illuminating are Vaughan’s detailed descriptions of the décor of her extensive Paris apartment at 17 rue Franklin, and its aesthetic aspirations. Coupled with a chapter by Thalia Laughlin and Carina Nandlal on the design of L’Oiseau-Lyre scores, in the hands of decorative artist Rose Adler, and a generous allocation of high-quality illustrations throughout the volume, you can only agree that Louise’s visual-arts collaborations are presented in the splendour that she so craved.

Other chapters detail her well-financed support of many contemporary composers (Murphy and Madeline Roycroft), her energetic promotion of the British Music Society in 1920s Melbourne (Sarah Kirby), and the driving of new partnerships, especially with the academic Yvonne Rokseth, in support of the revival of medieval music (Isabelle Ragnard). As the volume’s extensive Appendix of medieval and renaissance music recordings shows, Louise’s desire to produce 78rpm recordings of works found in the Press’s own editions only reached fruition in the late 1930s, presaging a much bolder expansion into more mainstream LP recordings from the late 1940s, all under the L’Oiseau-Lyre label.

A series of case studies of the Couperin edition – its impetus (Murphy), volume editors (Catherine Massip), context and launch (Susan Daniels), and press reception (Rachel Orzech) – deservedly takes a central position in Pursuit of the New. This was, undoubtedly, Louise’s finest hour, for which she was in 1934 appointed a Chevalier of the Légion d’Honneur. The War, with more restrained finances and dislocation, the postwar complexities of a rapidly internationalising business, the shelving of many pre-war enthusiasms before the heady lure of recordings, all conspired to deny her such focused recognition again, as publisher, collector, or cultural change-agent.

In an early review of Lyrebird Rising, ‘A Tornado from Toorak’, for Island magazine, Peter Stewart predicted that Davidson’s would be ‘probably the only biography she will ever have’. Given the fervour and quality of current scholarship, I cannot see our Louise settling for mere demi-god status. The definitive biography is yet to come.

Comments powered by CComment