- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Drugs

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Problem child

- Article Subtitle: A global psychedelic renaissance

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

An anthology dedicated to the transnational history of psychedelic drugs and culture seems a timely enterprise. We are twenty or so years into what has become known as the ‘psychedelic renaissance’, the global revival of interest in compounds such as LSD, mescaline, and psilocybin centring on their use alongside psychotherapy as treatments for a growing number of mental health disorders.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Ben Brooker reviews ‘Expanding Mindscapes: A global history of psychedelics’ edited by Erika Dyck and Chris Elcock

- Book 1 Title: Expanding Mindscapes

- Book 1 Subtitle: A global history of psychedelics

- Book 1 Biblio: MIT Press US$55 pb, 520 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

The book, which contains twenty essays on subjects as varied as soma consumption in West Bengal, the uses of ibogaine in Africa and ayahuasca in China, and the fate of LSD psychotherapy in South America, Israel, and communist Czechoslovakia, is divided into three parts. The first draws the reader into a variety of locations, prompting us to reflect on the ways the uses of psychedelics both cohere and diverge across dissimilar times, places, and sociocultural contexts. The second traces what the editors term the ‘global networks of knowledge’ which have facilitated the planetary (not to say cosmic) movement of substances and ideas. The third and final part explores how psychedelics have fomented and intersected with cultural, political, and technological change, challenging prevailing orders wherever people have chosen to ‘turn on, tune in, and drop out’.

Taken together, the essays constitute a useful reminder that the psychedelic renaissance, far from being sui generis, has roots reaching across continents and eras, and far beyond the United States and the ‘summer of love’ with which psychedelics have become synonymous. They also amount to something of a warning. Several authors here, including Zoë Dubas in her essay ‘Women, Mental Illness, and Psychotherapy in Postwar France’, reflect on the disturbing absence of ethical standards in the first wave of psychedelic research. Just as, in our own time, horror stories involving physical, emotional, and sexual abuse have emerged from psychedelic trials, Dubas and others document a wild west of manipulation, non-consensual dosing, and the exploitation of patients made vulnerable by acute mental illness as well as dynamics of gender, class, and race. As Stephen Snelders observes in his essay on LSD in the Netherlands, ‘in the 1950s, psychiatrists ruled their departments as feudal lords and developed the accompanying personality styles’.

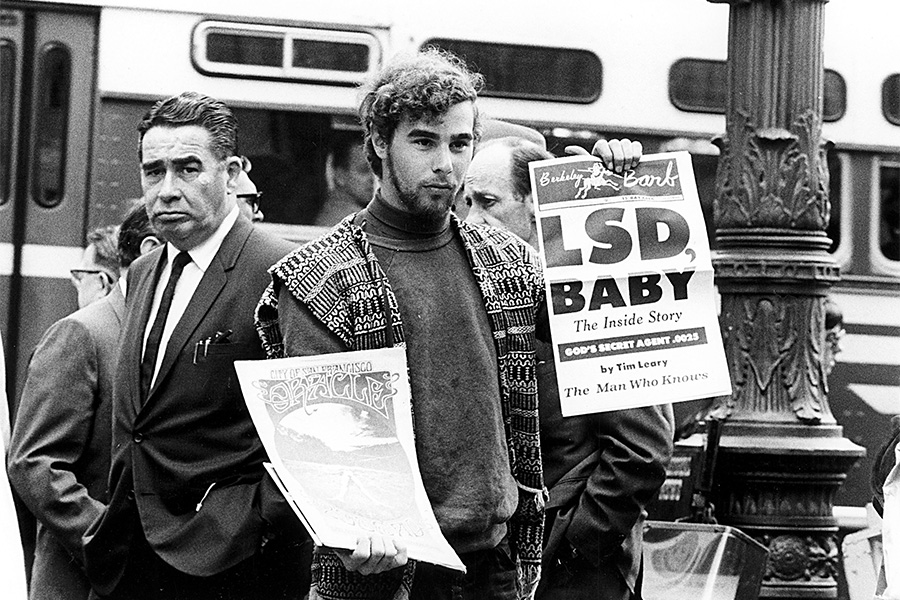

Promoting the use of the drug LSD in London c.1966 (Pictorial Press Ltd/Alamy)

Promoting the use of the drug LSD in London c.1966 (Pictorial Press Ltd/Alamy)

Nevertheless, the book falls short of its editors’ goals in important ways. Most obviously, its almost totalising focus on LSD – only around a quarter of the essays centre on a different compound – undermines the book’s claim to present an expansive, less Western-focused historiography of psychedelics (LSD was first synthesised by Swiss chemist Albert Hoffman in 1938, and subsequently globally distributed from pharmaceutical company Sandoz’s headquarters in Basel). Equally consequential is the editors’ decision to exclude from the book’s purview not only Pacific countries like Japan and Australia but also any First Peoples’ perspectives.

While several essays, including Timothy Vilgiate’s fascinating account of Voacanga africana in the ‘transnational imagination’, touch on the deleterious effects of colonialism and exoticisation, none centres on or is written by Indigenous people. This seems an especially egregious omission given the whitewashed nature of much psychedelic historiography, as well as the vigorous debates currently underway in global psychedelic circles relating to cultural appropriation and exploitation, and the marginalisation of First Peoples’ experiences. As is well known, the longstanding use of mind-altering substances in sacred and ritual contexts in the Global South predates the West’s ‘discovery’ of psychedelics by centuries.

The inclusion of indigenous perspectives would not only have gone some way to correcting the minimisation of this fact in the existing psychedelic literature, but it might also have led to a more compellingly heterogeneous book. As it is, many of the essays here hit the same beats with only minor variations. While, on the surface, it might appear interesting to juxtapose the psychedelic pasts of countries as disparate as England, Brazil, Israel, and the Netherlands, arguably more binds than separates these histories. Each account follows a similar trajectory: an initial wave of research beginning in the 1950s, focusing on the idea of LSD as a ‘psychotomimetic’ (i.e. psychosis-mimicking) agent; a shift in the 1960s to the exploration of psychedelics as adjuncts to psychotherapy; the near-total abandonment of research in the early 1970s due to the global prohibition on drugs; and finally, beginning as a trickle in the 1990s and turning into a flood in the first decades of the twenty-first century, the return of research with a renewed focus on the psychotherapeutic application of various psychedelics but most especially psilocybin and – though not in itself a ‘classic’ psychedelic – MDMA.

It is ironic that, while this anthology functions more as a history of LSD than of psychedelics, vanishingly few of the current clinical trials are exploring the uses of what Hoffman once dubbed his ‘problem child’. In 2024, LSD remains so, a drug still feared, misunderstood, and freighted with the subversive. While psilocybin and MDMA appear destined to be folded into an instrumentalised psychotherapeutic model (the book makes no mention of Australia having become the first country in the world to formally recognise these drugs as medicines), Mike Jay’s epilogue ponders what stands to be lost in the medicalisation of psychedelics: namely, their ‘striking potential as tools of creativity or social solidarity, ethnography or mass communication, philosophy or revolutionary politics’. At its best, Expanding Mindscapes presents a challenge to the medicalised and, increasingly, capitalised conception of psychedelic compounds which obscures their rich, protean history – and future.

Comments powered by CComment